Over the last few months there is a fierce sabre rattling in Eastern Mediterranean’s powder keg.

Fighting for Energy Routes, increased naval presence is gaining speed in the Eastern Mediterranean. There is a growing risk of direct confrontation between the regional states. It is impressive how much actual sabre-rattling is going on among the stakeholders.

Anastassios Tsiplacos - Managing Editor

“An incident at sea in which NATO warships end up actually shooting at each other seems an unimaginably bad outcome, but unfortunately isn’t out of the realm of possibility.” – Heiko Mass German Foreign Minister

Developments are accelerating in the maritime boundary dispute between Turkey, Greece and France. Belligerent statements and threats by senior government officials from the three countries, accompanied by multiple military deployments, aeronaval exercises and standoffs, are still far outpacing diplomatic efforts to head off an impending clash between the two -or maybe three- NATO members, endangering the Alliance’s Southern Flank or maybe a bigger flare-up out of proportions.

At the core of the recent crisis between Greece and Turkey lies a dangerous ideological model -not a mere dispute over energy resources. In the West, media outlets are mischaracterizing the true source of disruption in the Eastern Mediterranean. Although Turkey recalled its seismic research vessel Oruc Reis to the port of Antalya, this crisis is far from over -and now extends beyond Athens and Ankara. To be sure, Turkey’s Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman ideology is the primary reason the Eastern Mediterranean now looks increasingly more like the South China Sea.

While some assert that the crisis may be slowly de-escalating, one key dynamic all but guarantees a continuation of the tensions. Left unchecked, Turkey’s Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman inspired ideology will enflame regional tensions well into the future. However, before western actors can effectively deal with this phenomenon they must first acknowledge its existence.

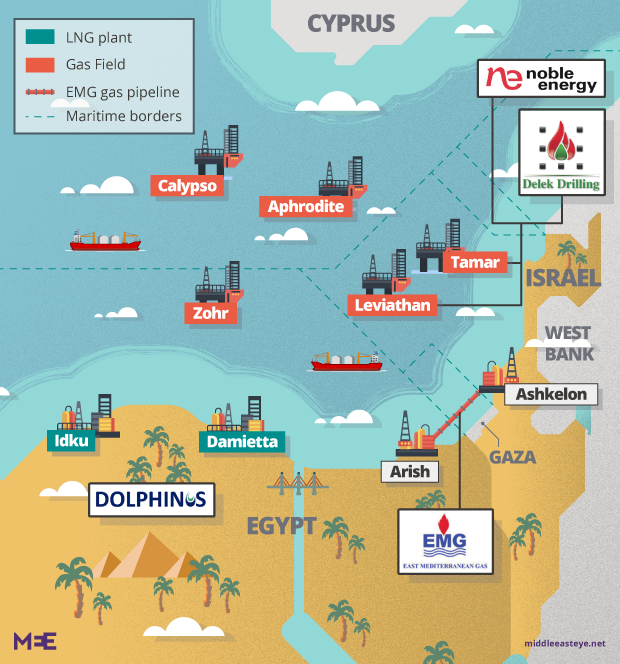

Energy sources of Eastern Mediterranean

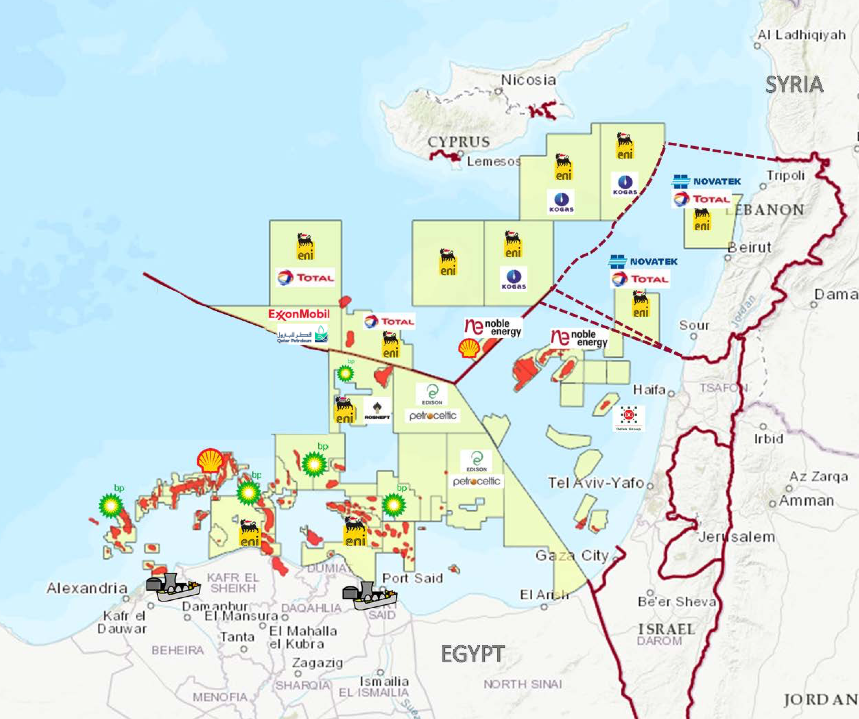

In the Eastern Mediterranean basin, which has a size of about 1/3 of Saudi Arabia, according to reasonable estimates lie big energy sources. Geographically it is divided into three areas: The first division is the Levantine Basin and includes the EEZs of Syria, Lebanon, Israel and the eastern part of the Cyprus EEZ.

In this basin, mainly in the Israeli EEZ, 460 boreholes were drilled and gas deposits containing 1.5 trillion c.m. were found of natural gas and 3 billion barrels of oil. In this area, the US Geological Survey (USGS Technical Report 2010) estimates that there are but 3.5 trillion c.m. of natural gas. Respectively, the Geological Survey of Israel estimates that there are another 8 trillion c.m. of natural gas and 26 billion barrels of crude oil.

The second area includes the Nile Cone, which lies exclusively within the Egyptian EEZ. About 1,900 drillings were made in this area and 1.8 trillion c.m. of natural gas were found without taking into account the “Zohr” deposit which geologically belongs to the third area. The US Geological Survey estimates that there are another 9 trillion c.m. of natural gas in this area.

The third area includes the Mediterranean Ridge. This ridge starts from the gulf of Kyparissia in Greece and ends at the ascent of Eratosthenes, i.e. south of Limassol in Cyprus. It essentially includes 3/4 of the Cypriot EEZ, a very small part of the Egyptian EEZ, where the “Zohr” deposit is located, the entire area south of the Dodecanese and the entire Libyan Sea (southern Crete and the Libyan Sea). The very probable gas reserves of the Eastern Mediterranean basin, always according to estimates, amount to a total of 48 trillion c.m.

The COVID-19 pandemic is only the tip of an iceberg of sociopolitical and economic challenges the Eastern Mediterranean is currently facing. What makes the Eastern Mediterranean so combustible today is the nexus of a number of complex and volatile issues, including: historic ambitions, conflicting assertions of sovereignty, competition over control of the newly discovered natural gas reserves, pipeline politics, civil wars and political chaos in the littoral states, US retrenchment, Russian naval base expansion in Syria, Turkey’s expansion in Libya, divisions among NATO allies, and waves of migration and refugees. The issues are exhaustive…

The Eastern Mediterranean is becoming ever more perilous as geopolitical fault lines steadily enmesh the region. Even though almost all exploration activities by oil companies are at a standstill due to Covid-19 and the crisis engulfing the industry, it is not stopping escalation of disputes in the region. The news continues to be led mainly by Turkey’s aggressions in the area, be it drilling in Cyprus EEZ, intervention in Libya or the threat of exploration and drilling in the seas between Cyprus and Greece.

The region has evolved into a multi-player security system, as non-western powers have been steadily increasing their presence and influence. Given that it remains a region of critical importance for Europe and the US, it is quite surprising that the very aggressive behavior of a member-state of NATO and a candidate for membership to the EU ,Turkey, against another member-state of both NATO and the EU, Greece, and a member-state of the EU, Cyprus, is being tolerated. The continuation of Turkish gunboat diplomacy will undoubtedly lead to the further destabilization of the region, at the expense of Western interests.

Over the last few weeks, there has been no shortage of analyses pointing to the mounting risks in the Eastern Mediterranean. In the end, most conclude that no party has an interest in going beyond bluster and the show of force for diplomatic leverage and domestic political advantage.

Why should the current tension over competing maritime claims in the Eastern Mediterranean be any different from past experience? There are good reasons to worry.

First, today’s tensions affect a far wider region with multiple flashpoints and actors. The Cyprus dispute, once a key source of risk in its own right, is now largely a political rather than a security question. Syria and Libya have become emblematic of the new regional geopolitics in which chaos is persistent, and conflict is open-ended. External actors have become bolder in the use of force, directly and via proxies. The roster of potential direct confrontations is long: Turkey with Russia in Syria or Libya; Turkey versus Egypt or the United Arab Emirates; and not least, Turkey with Greece, Cyprus, Israel -or France.

The old constraints and conservatism regarding the use of force by Ankara have waned, fueled by operational successes in Syria and Libya. This has been accompanied by a more explicit doctrine of maritime presence. The underlying claims regarding disputed sea and air space have not changed substantially. But the existence of valuable offshore energy resources and the growing capacity for power projection has changed the equation. In the tense years prior to the late 1990s, the Aegean was the center of gravity in Greek-Turkish friction. Today, the Aegean is back at the center, but the sphere of competition and potential conflict is far wider.

Energy and Geopolitics collide head-on in Eastern Mediterranean

The battle for a global showdown over the entire Mediterranean basin is ongoing. For example, Libya, which is as much Africa’s door as it is the Mediterranean’s, the U.S. military presence in Alexandroupoli vis-a-vis other Chinese harbors in Greece, China and the U.S. in Haifa -being infuriated to the extent to pull Israel’s ear- another harbor in Beirut being wiped off the map, the East Mediterranean which is the region’s heart, and the energy conflicts, which the subject of how profitable it is remains questionable, and many more. (see: REPORT #3: “Energy Wars”).

There is a lot of gas, but activity in the eastern Mediterranean for now is quite modest, compared to the world’s busiest offshore fields, such as those in the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, the Persian Gulf and offshore Brazil where hundreds of drilling rigs are busy sucking up oil and gas from thousands of wells. In the eastern Mediterranean, only about 50 wells have been dug so far in its ultradeep waters. The drilling is done mostly by semi-submersible rigs with gas now flowing by pipelines to Egypt and Israel.

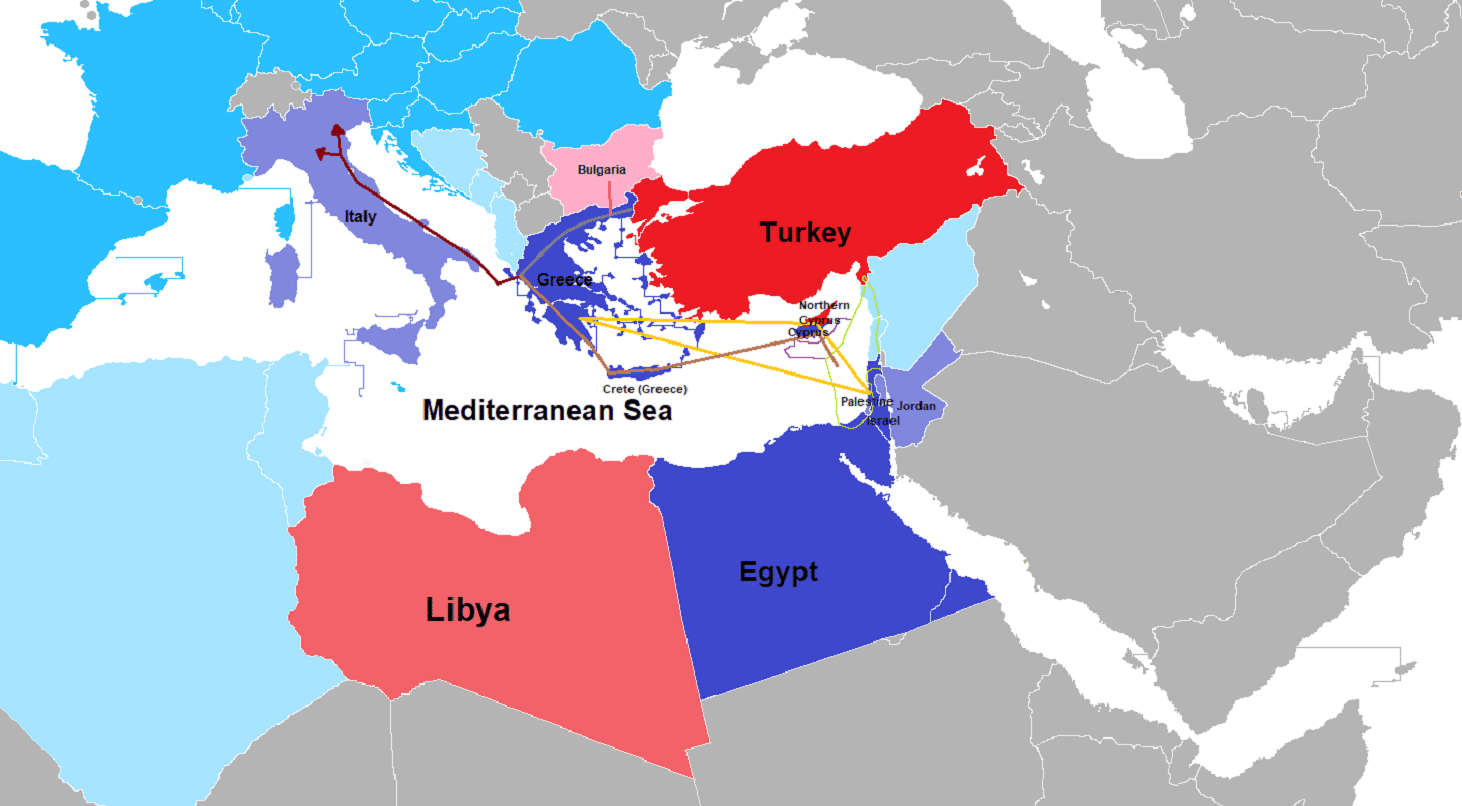

A collective interest in leveraging Eastern Mediterranean gas reserves increased cooperation between Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt, as well as key energy companies from the U.S., Israel, Italy and France. This grouping has grown to encompass Italy itself, Jordan, and Palestine, culminating in the creation of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF). Noticeably absent is Turkey -despite its overlapping maritime claims, vast domestic market, and potential as a transit route for regional gas exports. This coalition has received the backing of the United States, whose relationship with Turkey is also strained due to divergences on a growing number of issues.

Recent developments in Libya, together with the ongoing territorial disputes between several Eastern Mediterranean countries, especially the Turkey-Greece-Cyprus disputes over their respective EEZs, hinder exploration and development in the region, particularly in the offshore Levant Basin. If geopolitics is an argument about the future world order, then the Eastern Mediterranean Sea is shaping up to be a cauldron of quarreling visions and interests like no other. The geopolitical interests of the Eastern Mediterranean countries are bound to affect geoeconomic decisions concerning flows and exchanges in traded gas.

The International Energy Agency expects gas markets to be hurt long-term by the pandemic, which has left governments and business poorer. If the development of eastern Mediterranean gas fields began today, it would reach the market in around 10 years from now -which is precisely when the European Union’s climate plan calls for gas use to be cut 20%.

Gas developed by Turkey, Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt or other regional players may only ever be of value to themselves, rather than to the sizable Asian or European markets. The $8 billion EastMed pipeline, to which Cyprus, Israel, and Greece committed in January, is now probably just a pipe dream. If it happens, it will be because there’s been a geopolitical decision to somehow link Cyprus and Israel to Europe with something physical.

The list of troubled projects goes on; Egypt is struggling to find buyers and has cut production at its Zohr field. Exxonmobil, Italy’s Eni and French Total have suspended drilling operations in the eastern Mediterranean.

On the other hand, on July 20 the American oil giant Chevron Corporation announced its acquisition of Noble Energy, also an American company, which is a partner in the consortium that owns the Leviathan natural gas field, the site of 2/3 of Israel’s natural gas reserves. Great importance likewise lies in the timing of the announcement, which was issued against the background of the growing global doubt in the stability of the energy sector, and in the Israeli context, the declining trust of investors in the economic stability of some of Israel’s energy companies.

The irony is that, given today’s low prices, major oil companies are delaying further drilling. The transition to cleaner energy is continuing apace. Energy companies are becoming ever more selective in their investments. The longer that the eastern Mediterranean’s leaders bicker, the greater the chance that gas riches beneath the seabed will remain there.

Regional co-operation through Trilaterals

In the Eastern Mediterranean, a possible confrontation is under way between countries in the region, for access to gas fields. Conflicting legal claims to the fields are merging with old and new conflicts, and have led to the creation of a new geopolitical front that should cause stakeholders substantial concern.

Given the significant breadth of Turkish claims and its extremely maximalist positions on issues directly related to Greece and Cyprus, they deemed necessary to formulate a comprehensive policy and to utilize the entire foreign policy toolkit: alliances, bilateral diplomatic contacts and the opening of parallel communication channels, exploring prospects for bilateral and/or trilateral economic and other cooperation, while maintaining a strong capacity of deterrence.

Israeli, Cypriot and Greek energy ministers created joint task forces to evaluate the feasibility of several options. For exportation, they are considering the EastMed Gas Pipeline to carry gas from the region to European markets and a Cypriot LNG plant near Vassilikos on the southern coast of the island. However, other projects are simultaneously being evaluated by each government according to its own energy-security agenda and national interests.

The first Trilateral Summit between Greece, Israel and Cyprus took place on January 2016 and should be remembered for the leaders’ decision to create a committee for the planning of the EastMed pipeline, for the transportation of natural gas from Israel to Europe. In June 2017, Italy became part of this process and a working group for the supervision of the project was established. The agreement over the relevant text was achieved at the Beersheba Summit of 2018.

From then on, the two next summits (12/2018 and 03/2019) were actively supported by the United States, in accordance to the “Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act of 2019”, which allow the U.S. to fully support a 3+1 partnership shceme, through energy and defense cooperation initiatives.

THE EASTMED PIPELINE

On January 2, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Cyprus’ President Nikos Anastasiades signed the agreement for the EastMed pipeline that will transport gas from the Southeastern Mediterranean to Italy and the rest of Europe. Italy is also expected to sign the agreement at a later stage. EastMed pipeline is a huge project. If it is deemed technically feasible and economically viable, it will go ahead. There is also the prospect that East Med gas will be transferred via LNG ships. Depending on the quantities involved, the two transportation paths might prove supplementary. In any case, the message conveyed by this agreement is a loud one and its geopolitical symbolism is clear.

In addition, it will run smack up against a competing Turkish-Russian gas pipeline, TurkStream and against a potential Qatari-Iran-Syria pipeline.

Each country has its own reasons for becoming part of this project, as there are converging views on energy affairs and, among the participating states, common perceptions of threat. Additionally, the creation of the EastMed pipeline is crucial for Europe’s energy security, as it adds to the reduction of dependence on Russian, Arab-Muslim and Iranian hydrocarbons, something that is seen positively by the US and the Western world as a whole (see: REPORT #6 EASTMED: A pipeline of Peace or War? ).

From the geopolitical angle, for Israel, Greece and Cyprus, as well as the U.S. the EastMed does not represent a simple gas supply pipeline, but a comprehensive strategic plan involving capital and other means, as well as the creation of security conditions in the region. The strong ties between Athens, Jerusalem, and Nicosia go well beyond the promotion of open communication links in the field of energy. The geopolitical/security perspective is crucial. Article 10 of the agreement contains provisions on measures to protect the pipeline. The relevant provisions are considered very important, as such clauses are not included in similar agreements (see: The Day After EastMed Agreement… ).

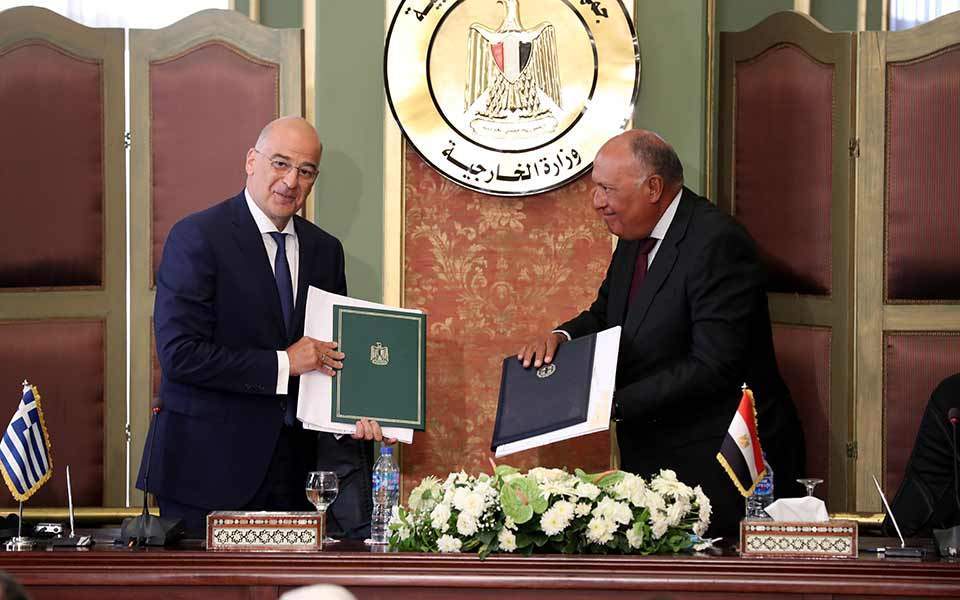

The second major regional Trilateral is between Egypt, Greece and Cyprus. Unlike previous trilateral summits, which focused on all the issues of cooperation between the three countries, the 7th Trilateral Summit on October 2019 in Cairo, aimed at forming a strong energy-based alliance in the Eastern Mediterranean. The joint declaration stated that the three countries underlined the importance of making additional efforts to boost security and stability in the region, and strongly called on Turkey to “end its provocative actions” in the Eastern Mediterranean condemning them as “unlawful and unacceptable”.

All the more, Cyprus and the “Aphrodite” consortium signed an exploitation license and a revised production sharing contract, aiming to start natural gas production in 2025. The 25-year exploitation licence is the first of its kind signed with Cypriot EEZ licensees and it’s based on the final development and production plan of the “Aphrodite” field. Shell will be the buyer of Aphrodite’s natural gas. It will be transferred via a subsea pipeline to Egypt’s Idku LNG plant from where it will be liquified and exported to European and international markets.

As a recent development, Greece continued its diplomatic campaign, after the recent deliniation aggreement with Italy and in a surprise move, the Greek Foreign Minister secretly jetted off to Egypt, to sign a maritime treaty between the two countries that partialy delimited an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in an area containing offshore oil and gas reserves, finalizing the strategic alliance with Cairo, upgrading their 8-year long relations.

This development had a really bomb-like effect in Ankara and elsewhere in Turkey infuriating, to say the least, President Erdogan and the architects of Turkey’s so-called “Blue Homeland” naval expansion doctrine.

In the wake of this Agreement the Turkish President described it as nonexistent, denounced it as invalid and announced drilling operations in areas overlaping Greece’s continental self, albeit out of the delimited EEZ with Egypt, and also called off exploratory talks with Greece whose commencement on August 28 had been expected.

Joint Aeronautical Exercises

To enhance their co-operation and send the message that they “mean business” Egypt, Greece and Cyprus have been intensively involved in joint exercises, during the last 6 years, in order to enhance the security character of their cooperation. Within the framework of this practice, the large-scale, “MEDOUSA” exercises, for air and naval forces of Greece and Egypt, take place in the wider region of Alexandria, Crete and the Eastern Mediterranean. For the first time on Egypt’s part the Mistral helicopter carrier participated in Greek waters, and actually Greek Chinook CH-47D and Apache AH-1A attack helicopters both landed and operated from it.

The exercise scenarios are gradually being expanded and the participating forces are also increasing both in size and in the variety of the hardware involved.

The breakdown of the participating forces indicate the scale of the exercises. Greece usually participates with 2 frigates and their on-board helicopters, 1 submarine, 8 F-16s, 1 C-130, 1 AWACS aircraft, 1 CHINOOK helicopter, 2 AH-64 attack helicopters and Special Forces personnel. Egyptian forces participate with a MISTRAL class helicopter carrier, 2 frigates, 1 submarine, 2 missile boats, 6 F-16s, 2 RAFALEs, 1 E2-C AWACS aircraft, 1 helicopter and Special Forces personnel. Cyprus participates with an offshore patrol vessel, and Special Forces personnel.

In parallel, the combined military exercises and co-training of Greek and Israeli armed forces have increased over the past five years and include the whole range of exercises (army aviation, Special Forces, air and naval forces). Israeli aircraft also participated in the INIOCHOS multinational exercise at the Air Tactics Centre at Andravida airbase. Dozens of Israeli aircrafts were deployed in long-distance missions, with constant air refuelling, from Israel to the greater airspace of Crete. Israeli F-16I, F-15I and F-35I “Adir” aircrafts flew en masse inside the Greek FIR, south of Crete.

The co-operation has worked mostly for the Israeli Air Force as Greece operates the Russian-made S-300 defense system. Since Syria and other Middle Eastern countries are also equipped with a similar Russian system, training against these missiles has helped IAF to get aquainted with the system and eventually combat Iranian positions in Syria by neutralizing the S-300 system.

Last but not least, Cypriot and Israeli forces have been participating in corresponding large scale bilateral exercises (“Onisilos – Gideon”, “Nikokles – David”, “Jason”) since 2014. The program of tripartite military cooperation between Greece, Cyprus and Israel for 2021, that was signed on September 9, will further enhance the military cooperation between the Armed Forces of the three countries, by joint exercises and operational activities.

It is more than evident that all the above exercises, go beyond the usual level of combined exercises to exchange experiences and strengthen bilateral relations. Their scenarios are extremely complex with a very large number of participating forces and hardware, indicating that all four countries are intensely promoting their military cooperation to a great extent and very frequently, to prepare for combined military action if necessary, but also to send convincing messages to Turkey that threatens to prevent this kind of co-operation.

NATO’s Southern Flank in danger of dissolvement…

A possible confrontation between the three NATO members France, Greece and Turkey continues to trouble the Alliance’s Southern Flank. The triggering momentum for the current rise in tensions was when Turkey dispatched a naval-escorted surveyor ship to contested waters near the Greek island of Kastellorizo, as well as two drilling ships in Cyprus’ EEZ. Greece then put its armed forces on high alert and French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to boost France’s military presence in the eastern Mediterranean to counter Turkish aggressiveness.

Turkey’s intentions are a real threat for the integridy of NATO’s Southern Flank, remininscing the old 1974 day’s of its ATTILA invasion in Cyprus and the dissarray it caused back then to the Alliance. A confrontation between the two NATO members, Greece and Turkey, continues to trouble the Alliance’s Southern Flank after 46 years (see: REPORT #5 NATO in Eastern Mediterranean: The Haze of Energy War…).

The main destabilizing factor for NATO’s Southern Flank is Turkey’s independent policy in the Middle East and North Africa. The so-called ultra-nationalist “Blue Homeland” military strategy is clear in its goals. President Erdogan’s military doctrine targets the domination of the Aegean, most of the Mediterranean, and of the Black Sea.

Increasingly assertive, ambitious and authoritarian, Turkey has become the “elephant in the room” for NATO. A more aggressive, nationalist and religious Turkey is increasingly at odds with its Western allies over Libya, Syria, Iraq, Russia and the energy resources of the eastern Mediterranean. However, Alliance’s officials also suggest that Turkey is “too big, powerful and strategically important…to allow an open confrontation.” (see: “Will Turkey dare to dissolve NATO’s Southern Flank?”).

NATO’s Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has repeatedly declared support for Turkish activities in Eastern Mediterranean, as allegedly stopping Russian expansion in this region. Unfortunately, this approach only deepens the division of the Alliance and causes countries such as France or Greece to try to get along with Russia as the only entity that can influence Turkey. For the Kremlin, however, this is an ideal situation, a dissonance in NATO is in itself desirable, especially since it cannot be ruled out that it will end in conflict. However, entering the role of a mediator gives it full opportunity to safeguard it’s own interests.

Nevertheless, despite numerous disagreements, one part of the US establishment likes to persist that Turkey remains one of its main allies in the Middle East. Over the past year, the American unwillingness to lose this partnership relation is evidenced by numerous occasions, either in the withdrawal of the US military from northern Syria in October, or in the relactunce of President Trump’s to impose sanctions over Turkey’s aquisition of the Russian made S-400s.

On June 10, a French frigate on a NATO mission tried to inspect a Tanzanian-flagged cargo ship suspected of smuggling arms to Libya. France says the frigate was harassed by Turkish navy vessels escorting the cargo ship, and accuses Turkey of breaking a U.N. arms embargo. Turkey denies this, and says the frigate was aggressive (see: France, Turkey, NATO & Libya…)

A NATO investigation into the naval standoff between the French and Turkish ships has been rated too sensitive to discuss in public and does not apportion blame, as Paris and Ankara wage a war of words. The issue underlines NATO’s difficulties with Turkey, also at odds with Greece over energy rights and with the alliance’s leader, the United States.

It now seems unlikely that the investigation can resolve the spat. A NATO official confirmed the report had been finished, but declined further comment. “It’s been swept under the carpet,” he said.

While the US affords to accept Turkey’s policy, its NATO ally, France, is increasingly critical. Thus, on June 17, the French Defense Ministry urged NATO to address its “Turkey problem” amid rising tensions over Libya and other issues. The current crisis within NATO and the EU, sparked by Turkish actions is a major concern. A military conflict within the alliance will not only weaken its position with regards to Russia’s power projections, but also puts security in the region at risk.

Turkish President Erdogan’s “disturbing” foreign policy has spurred U.S. officials to intensify preparations to withdraw from Incirlik Air Force base. President Erdogan has threatened American access to the base, which reportedly houses dozens of U.S. nuclear weapons, multiple times since he squashed a failed coup attempt in 2016. Although officialy denied, Washington is not necessarily thinking of one alternative to Incirlik, but a number of rebasing options which are complementary as a contingency plan to Incirlik. A withdrawal would signal a major shift in the balance of trust between the United States and the country that boasts the second-largest military in NATO.

Nevertheless, membership in NATO gives Turkey the opportunity to manipulate the positions of other member countries, since all decisions of the organization are made by consensus. A U.S.-NATO intervention or a concentrated EU move in the case of Turkish action seems unrealistic, and President Erdogan seems to know this based on his recent actions. As long as Europe and NATO keep a low profile without countering Turkish moves, Greece and Cyprus will be the next targets for a Turkish military move with immeasurable results for the region and the Alliance’s Southern Flank.

Should there be a military confrontation between Greece and Turkey, NATO’s Secretary-General may find himself in the awkward position of delivering to his successor the Alliance minus its southeastern flank. Neither can the EU any longer afford to allow various third parties to shape its southern neighborhood without Europe’s active involvement.

Europe’s Ambivalence…

The Eastern Mediterranean has become a nexus of flashpoints that draw the European Union and Turkey deeper into an adversarial relationship. Once confined to territorial sovereignty disputes among Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey, the region’s offshore natural gas resources have transformed the Eastern Mediterranean into a strategic region, in which larger geopolitical fault lines involving the EU and the Middle East and North Africa converge.

Turkish quasi-victories in Syria and Libya have been made possible by Washington and Europe’s unwillingness to stand up to President Erdogan, which only feeds his sense of invincibility. Many European countries go along with Turkey’s whims or are willing to tolerate its provocations in the Eastern Mediterranean either because they are worried about the migrant influx, which Erdogan appears to be in control of, or because they have strong economic interests at stake, including arms sales to Turkey: Germany builds submarines for the Turkish Navy, while Turkey’s first aircraft carrier is being built with Spain.

The main reason for what has surely developed into a new European fear is clear: Behind closed doors, major EU representatives agree that Erdogan regime is lesser of two evils. Erdogan’s fall will wreak havoc in Turkey, they maintain, incomparable to what happened to the former Yugoslavia, causing millions of Turks to flee west on to EU soil. So, the Erdogan regime is considered “fine”, as it offers stability, even though the entire country is “an open-air prison.” Thus, “let us remain paralysed” they say, while they continue to appease mr. Erdogan, pretending everything is just fine.

As a result, Turkey feels free to roam the Eastern Mediterranean, signing illegal agreements and sending troops to Libya, threatening to carry out energy exploration within Greece’s EEZ and preventing foreign firms from drilling in Cyprus’ EEZ, which by the way they are european EEZs too, while Brussels remains complacent and is only just starting to mumble about possible sanctions.

Nevertheless, some south european states are understandably concerned about Turkey’s unfolding interests across a large part of the region and its effort to establish footholds along the North African coast. Turkey’s expansionism presages a series of developments that could trigger unrest and changes in Europe.

No one can ignore the looming threat of a fresh migration wave across the Aegean and the purported astonishment of Turkish officials over Greece’s failure to offer a heartfelt welcome to the devastated hordes, that are being forced by Ankara in the direction of the Greek islands. Many are beginning to realize that should Turkey achieve its objectives in Libya, the migration issue will acquire a new dimension, potentially affecting not only European Union countries on its southern coasts this time around, but mainland Europe as well.

Obviously, Germany is keen to preserve the relationship between the EU and Turkey. While the Turkey-GNA accord touched off a new round of diplomatic fireworks between Paris and Ankara, as well as renewed EU declarations of unequivocal support for Greece and Cyprus, Germany fostered a more conciliatory tone towards Turkey at the January 2020 Berlin International Conference on Libya.

Germany attempted to follow through on the Berlin conference by positioning the European Union to set up the mission EUNAVFOR “IRINI”, to monitor the UN arms embargo on Libya. The EU strives to speak the language of power but keeps failing in Libya, where two members, namely Italy and France, are pursuing very different goals. Rome is anxious about migration while Paris cares more about the terrorist threat. But both have an interest in energy sources.

Following Brexit, France is the EU’s greatest military power. President Emmanuel Macron understands the need to meet the Turkish challenge head-on, whereas EU and NATO appear indifferent to the fact that their boundless tolerance of Turkey’s behavior is threatening the Alliance’s cohesion. The French President’s reaction is expressed in a straightforward manner, contrary to Italy’s prevarication and Germany’s apparent reluctance to take a more firm stance.

The EU needs to make a clear decision about re-setting its relationship with Turkey in a balanced manner, linking benefits with obligations and a code of conduct. Such a relationship cannot be exclusively transactional; values, as well as attitudes, remain important. A combination of mr. Macron’s muscle and mrs. Merkel’s mediation could yet prove effective in convincing Turkey that, though its rule-breaking cannot be accepted, its concerns will be listened to. The priority is to create some breathing space for Greece and Turkey to talk.

LIBYA’s ΗΟΤ ΖΟΝΕ: An Energy War at large…

Libya’s proxy war and Turkey’s active involvement shows how the Eastern Mediterranean has turned in a few years from a backwater, on the fringes of Middle East turmoil, to a major hot zone. What makes the new tension in the region so confusing is how old rules and alliances have been blurred. Turkey’s alleged violation of the arms embargo came weeks after its vessels had joined allied navies for a NATO exercise off the Algerian coast. As Libya burns, tensions are also rising over new gas fields in the region.

The U.S. Defence Department reported recently that Turkey has sent between 3,500 and 3,800 mercenaries to fight in Libya over the first three months of the year. The figures are stated in a quarterly report on counterterrorism operations in Africa by the Pentagon’s internal watchdog.

The Pentagon said Turkey has paid and offered citizenship to thousands of mercenaries fighting alongside the Tripoli-based, United Nations-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) against the forces of eastern-based rebel General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), which is backed by Russia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates, among others. The U.S. military found no evidence to suggest the mercenaries were affiliated with Islamic State or al-Qaida, despite widespread reports of their links to radical Islamist and jihadist groups, according to the report. The report said the fighters were most likely motivated by financial packages, rather than ideology or politics.

The report only covers until the end of March, two months before the Turkish-backed GNA won a series of significant battlefield victories against Haftar’s forces; forcing them to retreat from Tripoli’s suburbs and from key strongholds at Tarhuna and al-Watiya air base.

The Pentagon said Turkish deployments likely increased ahead of the Tripoli forces’ victories in late May. It cited the U.S. Africa Command as saying that 300 Turkish-supported Syrian rebels landed in Libya in early April. Turkey also deployed an unknown number of Turkish soldiers during the first months of the year, it added.

Libya reveals how Turkey blackmailed the country into energy and mercenary deals

Revelations by Libyan officials to the Associated Press have lifted the lid on more than six months of questions about how Turkey was able to push Tripoli to accept thousands of extremist Syrian mercenaries in exchange for Ankara getting energy rights -leaving Libya with little gains except being saddled with extremists.

Last November, Libya’s embattled Government of the National Accord was under siege in Tripoli by Khalifa Haftar. General Haftar, with a rival government based in Benghazi, appeared to be on the verge of ousting GNA. Suddenly Ankara, which along with Qatar had backed the GNA with limited weapons and financing, swept in to offer a deal: Turkey would get energy rights off the coast which would let it threaten Greece and potentially harm Israel’s interests in an East Mediterranean pipeline, and Ankara would aid Tripoli with Turkish officers and technicians, drones and Syrian rebels.

Turkey could count on support or silence from the European Union, NATO and the United Nations because it was threatening to force hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees into Europe in the winter of 2019. The message was clear to the European Union: Either let Turkey seize a swath of the Mediterranean and take over part of Libya and send Syrians there, or the Syrians -some of whom were extremists- will be Europe’s problem. With Germany and other European countries paying Ankara billions to keep Syrians in Turkey, there wasn’t much choice.

Now the Libyan side of the story can be told in more details: We know that since Turkey has escalated the conflict in Libya, which previously was a ramshackle civil war with limited backing from a plethora of foreign powers, the Russians have sent warplanes, and Egypt has threatened to intervene.

In short, Turkey’s involvement has made Libya a much larger conflict with stakes that now link to all of Europe and the Middle East. It has become a testing ground for Turkish drones, Russian air defense and Chinese armed drones, and has brought Egypt, the UAE, Greece and France closer together to complain about Turkey’s role.

The AP reports assert that Turkey sent up to 3,800 mercenaries and some troops to support Libya’s GNA, which is run by Prime Minister Fayez Sarraj. “They took advantage of our weakness at the time,” the Libyan officials now say. Turkey’s media called the Libyan war a “revolution” like the Arab Spring, fighting against “warlords.”

However, it now turns out that Ankara was pressuring Sarraj for a year for the energy and maritime deal. Turkey was the only country really ready to give support. It now appears that Turkey will milk Libya economically. The AP report says Ankara has given Tripoli a bill of $1.7 billion for money owed to Turkish companies. A role in oil and offshore energy and then military bases will likely come next. Tripoli appears to be concerned that it is becoming another colony of Ankara, similar to the instability Turkey unleashed in northern Syria, where local voices become subservient to its whims, but have little control over their own destiny.

Turkey appears to be determined to increase its military presence in Libya, deploying Syrian militants and jihadists of different nationalities. Recent reports revealed that Ankara is planning to establish permanent bases for its forces in the Arab country. According to the monitoring group, Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), a new batch of Syrian militants and jihadist arrived in Libya in the past months.

The SOHR estimates that Turkey has deployed more than 17,000 Syrian militants, including 350 children, in Libya so far. At least 6,000 of them returned to Syria in the recent few months after receiving their full payment. Besides deploying its Syrian proxies, Turkey also transported around 10,000 Jihadists of different nationalities to fight for the GNA in Libya. At least 2,500 of them are Tunisian.

The Sudanese Intelligence released an official report pertaining to links between the Brotherhood and Libya’s GNA, the Bashir government, and other African countries. The report shows that after the fall of Bashir, the GNA reached out to radical Islamists and conscripted them to fight in Libya.

Turkey and other actors backing the GNA are directly facilitating this expanding foreign network of globalized Islamist combatants as they take over local conflicts. The ultimate objective is a return to the “Ottoman Empire” according to Turkey’s “defense line” parameters, or to an Islamic Caliphate according to the terms of the Muslim Brotherhood affiliates, including al-Qaeda and a newly resurgent ISIS.

The aforementioned U.S. Defence Department report comes as the Libyan conflict has escalated into a proxy war with foreign powers pouring weapons and mercenaries into the country, stressing that Russia has also sent hundreds of mercenaries to back Haftar’s siege of Tripoli. The Wagner Group, a private Kremlin-linked military company, sent snipers and armed drones to Libya last autumn. This year, in response to Turkey’s shipments of battle-hardened Syrians, Wagner increased its deployment of foreign fighters, also including Syrians, with estimates ranging from 800 to 2,500 mercenaries.

Russia denies any direct engagement in Libya, but there are at least 14 MiG-29 fighters in the al-Jufra base, as well as some Sukhoi-24 bombers, and also Pantsir anti-aircraft systems. Allegedly, in the bases still linked to General Haftar, there are also Serbian and Ukrainian mercenaries, connected to the Wagner networks of Russian contractors. They are mainly in the base of Gardabyah, but although denying any direct military interest in Libya, Russia has reportedly deployed its 900 “militants” in Libya in the bases linked to Haftar, as done also by Turkey.

It’s all about oil and gas

When Colonel Muammar Gaddafi was reintegrated in the “community of the good ones” in early 2004, after a curious British legal twisting on the Lockerbie attack of December 1988, a bonanza for oil and gas concessions started. The Italian energy company ENI and BP were among the first to have a big foot in the door. Studying some of those contracts the eloquent question was why companies were ready to accept such terms. The answer was maybe in the then rise in the price of oil and the proximity of Libya to the European market.

In August 2011, as Libya’s rebels and NATO jets began an assault on Tripoli, Gaddafi delivered a speech calling on his supporters to defend the country from foreign invaders: “There is a conspiracy to control Libyan oil and to control Libyan land, to colonize Libya once again.” he said in a message broadcast by a pro-regime television station. Two months later, the dictator was dragged bleeding and confused from a storm drain in his hometown of Sirte, before being killed. Nine years on, after the outbreak of a second civil war, Gaddafi’s proclamation is not far from the truth. As the battle moves to Sirte, gateway to the country’s oil crescent, a potential showdown over control of Libya’s oil wealth is looming.

Interestingly, in September 2011, the very day of the opening ceremony of the Paris conference dubbed “Friends of Libya,” a secret oil deal for the French company Total was published by the French daily “Liberation”. The “good opposition” had promised the French an interesting range of oil concessions. Oil production continuously fell with the rise of the war, attracting sponsors, militias and smugglers from all horizons. The situation in Libya has since been called “somalization”, but it would become even worse, since many more regional powers got involved in Libya than ever was the case in hunger-ridden Somalia.

Over the last nine months, the Libyan National Army (LNA) has held a stranglehold on oil exports. Haftar’s economic strategy has been successful thus far. He seeks to deprive the UN-recognized government of critical funds and make eastern Libya the financial capital. The LNA, however, has struggled militarily as of late, suffering defeat after defeat since June. Now the LNA is looking to negotiate using the oil fields for leverage, effectively keeping the economy hostage. Libyan oil exports have been reduced to around a tenth of their original production.

Washington said that it would sanction Haftar’s foreign backers if they obstruct the return of oil flow. Immediately after, Wagner mercenaries moved into southern oilfields and the coastal al-Sidr terminal. In a dashing move seized the Es Sider oil field and port, and reports indicate it has set up camp to monitor its new asset. While this move benefits mr. Haftar and the LNA, Russia is protecting itself. Securing the oil fields ensures that Russia can push for access no matter who wins the civil war. It should be noted that Es Sider influences the oil production for the US-based Hess Corporation and ConocoPhillips along with one of the largest energy producers in Spain, Repsol. The Es Sider oil field was also one of the main economic pipelines for the Government of National Accord.

Libya’s oil blockade lasts for 9 months now and the war-torn country’s oil output is hovering at just 100,000 b/d instead of the pre-crisis 1.2 million b/d. Without a peaceful solution on the horizon, its expected restart is delayed to fourth-quarter 2020, according to a recent Rystad Energy forecast.

In the most optimistic of scenarios, Libya’s 2020 exit production rate will be 700,000-800,000 b/d. But this estimate itself carries a downside risk: once oil production comes back online, it would take Libya another 3-4 months to ramp up production to the 1 million b/d mark.

The damage is not just limited to the short term. The prolonged blockade has negatively impacted both infrastructure and oil wells, so the eventual production ramp up will demand capex spending to rehabilitate wells and pipelines. For this purpose, Libya’s National Oil Company (NOC) estimates that between $500 million and $1 billion is needed just to reach the pre-blockade levels of 1.2 million b/d. (see: Why Libya’s Civil War lingers… in “OP “IRINI”: The Force that watched arms go by incompetent or unwilling to take action… “)

On August 21 the UN-backed government of Libya announced a ceasefire and the east-based rival administration also called for a truce in a move that could pave the way to reopening of Libya’s oil terminals, if the ceasefire holds. However, the first hopes were drowned after the opposition Libyan National Army dismissed the ceasefire proposal as a “deception”, saying that GNA-allied militias were preparing an assault on the strategic coastal city of Sirte. The proposal “represents nothing but throwing dust in eyes and deceiving the local and international public”, LNA spokesman Ahmed al-Mosmari said.

Nevertheless, General Haftar recently announced lifting the blockade on oil production and its export, hours after the Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC), in a statement, objected to “the politicization of the oil sector and its use as a bargaining chip for political gains.” In his speech, however, the general did not refer to the cease-fire initiative that has been underway in the country for about a month.

Libya transformed into air warfare laboratory

Libya has been transformed into a battle lab for air warfare, with involved countries testing their military capabilities against one another. The skies over the North African country have filled with Turkish and Chinese drones, Russian MiG 29s and Sukhoi 24s and Emirati Mirage 2000s reportedly, with Turkish F-16s and Egyptian Rafalles on standby.

Around May 2019 -just one month after Haftar launched an assault to capture Tripoli- Turkey introduced the Bayraktar TB2 drone to support the GNA, attacking Haftar’s forces, knocking out Russian Pantsir air defence systems supporting him and ultimately helping end the operation. Turkey has majored in UAV design and manufacture and likely used Libya in part as a test and adjust battle lab, and its systems are now “combat proven”. Its industry has also developed small, precision-guided munitions for UAVs.

Turkey’s use of the TB2 in Libya had been a gamechanger. Turkey decided it was okay to lose them from time to time, that they were semi-disposable and that novel approach caught their enemy off guard. They used to cost the Turks $1-1.5 million apiece to build, but thanks to economies of scale as production volumes rose, the cost has dropped to below $500,000, excluding the control station.

Compared with the Chinese-made Wing Loon II drone, which the UAE used to bomb Tripoli, TB2’s software and other technical changes has boosted its efficiency and reconnaissance capabilities that allowed them to find the right altitude to avoid the Russian Pantsir systems.

According to various reports, UAE Mirage 2000-9 aircrafts flying out of an Egyptian base had been supporting Haftar periodically since June 2019. Misrata airbase, which has hosted Turkish TB2 drones, was bombed multiple times last year by Emirati drones and jets until the Turks brought in Korkut and MIM-23 Hawk air defense systems. On July 5, fighter jets attacked al-Watiya air base, shortly after GNA-allied forces recaptured it and Turkey had brought in its MIM-23 Hawk air defense missiles there.

Evidence showed the jets took off from Egypt then flew over the Sahara Desert to avoid detection by Turkish frigates off the Libyan coast. Could it have been Egyptian Rafales? They are good but don’t have enough experience for an ultra-precise mission like this. French pilots flying Egyptian Rafales is unlikely in case one was captured, leaving the UAE Mirages as most likely. International defence analysts say that of all the Gulf states, the UAE is the most capable of this kind of mission. They have the combat experience and could do this (see: “Al-Watiyah’s hit exposed Turkey’s limitations…”).

On the other hand, Turkey may be considering basing its F-16s at the now-repaired al-Watiya air base, however deploying U.S.-built fighter jets may rely on the United States permission. Is the U.S. so concerned about Russia’s intervention in Libya it would support the deployment of Turkish F-16s to stop it? Or will it come down on the side of Egypt, which is a U.S. ally too?

Towards a ceasefire solution…

On August 21 the UN-backed government of Libya announced a ceasefire and the east-based rival administration also called for a truce in a move that could pave the way to reopening of Libya’s oil terminals. However, the first hopes were drowned after the opposition Libyan National Army dismissed the ceasefire proposal as a “deception”, saying that GNA-allied militias were preparing an assault on the strategic coastal city of Sirte.

Neverteheless, it seems that Turkey and Russia have moved closer to an agreement on a ceasefire and political process in Libya during their latest meetings in Ankara. In this respect, there was an inter-Libyan dialogue held in the coastal Moroccan city of Bouznika from September 6-10, which brought the rival parties together in the Libyan crisis.

At the same time during the last month, the interim government of Libya, supported by the army of General Khalifa Haftar, submitted its resignation to Parliament. Almost immediately afterwards, the Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj announced too that he intends to step down by the end of October.

The resignation of the head of the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA), Fayez al-Sarraj, took most of the stakeholdes by surprise, even though several leaks in the press about a week ago should have prepared them for it. While some view Sarraj’s resignation as a procedural step to pave the way for the next government of national unity, others see it as reflecting the failure of his attempts to prevent his being excluded from the scene, especially when Interior Minister and rival Fathi Bashagha was reinstated in his post.

Most political interpretations of this particular development were almost all unanimous that mr. Sarraj was subjected to strong pressures, related to international arrangements being prepared in several Western capitals, especially in Washington, for a quick settlement in Libya through reshaping the political scene before the coming U.S. elections. Many believe that Sarraj’s resignation was brought about by strong U.S. pressure with the purpose of appeasing international parties disturbed by the agreements he signed with Turkey, especially the maritime border demarcation agreement that angered the Europeans in general and France and Greece in particular.

Sirte, one of Libya’s key oil ports, has been the focus of the ongoing talks between the country’s warring parties for the last few months. Sources familiar with the ongoing talks have said that there is an initial understanding to demilitarize Sirte in order to turn it into a headquarters for a new “national authority” that will succeed the UN-recognized GNA. The sources also claimed that Russia and Turkey had reached a secret agreement to withdraw all foreign fighters supporting the LNA and the GNA from Libya. Moscow and Ankara are allegedly eager to help form a joint LNA-GNA force with tribal fighters from Libya’s three provinces, Cyrenaica, Tripoli and Fezzan.

Delegations from the LNA-backed House of Representatives, HoR, and the GNA are set to start a new round of direct talks in Morocco. The last round saw some progress, according to several sources. Today Libya appears to be closer than ever to a political settlement between the LNA and the GNA. Pressure from Russia, Turkey as well as the U.S. is forcing both sides to compromise.

Interests at Stake…

Eastern Mediterranean gas remains incredibly important for states in the region as they seek to enhance their energy security and drive economic development. The United States Geological Survey estimates that the Levant Basin – the waters of Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and Palestine – contains 122.4 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable gas. To date, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, and Palestine have discovered gas -which has stimulated cooperation between Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus. Turkey, however, disputes the right of the Republic of Cyprus to conduct gas exploration without the involvement of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC).

Nine states (Israel, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Russia, Italy, France and USA), five of them the oldest NATO members, have major to very high stakes in the “Big Game” of Eastern Mediterranean’s region. The experience of recent years suggests that ensuring peace and stability in the region is first and foremost the responsibility of these regional powers.

Gas production would be a veritable boon to cash-poor Cyprus and Lebanon. Egypt and Israel are cooperating in trading and re-exporting gas. Turkey has practised brinkmanship to defend what it believes to be its rights to conduct gas exploration around most of the island of Cyprus, but would similarly benefit from discoveries of its own. Italy’s Eni has the largest stakes in the region, with massive holdings in Egypt and exploration blocks off the Republic of Cyprus and Lebanon. Other Western companies – including BP (United Kingdom), Total (France), Kogas (Korea), ExxonMobil (United States) – have joined Eni in Cyprus, while BP (UK) owns the lone field in Palestine. BP has considerable holdings in Egypt, while Noble Energy (United States )-under Chevron’s group now- and Israeli companies own Israeli fields. Lastly, Russia’s Rosneft and Novatek have stakes in Egypt, Libya, Syria and Lebanon respectively (see: REPORT #4 ‘S.E. Europe – S.E. Mediterannean. Multiple Energy Challenges and Complex Geopolitics”).

TURKEY: Like a lorry in downslide without brakes…

“Political Vision 2023,” portrays Turkey as a rising global player, a powerful mediator for peace and stability in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean. The Vision’s statement specifically notes the place of energy in foreign policy, and highlights Turkey’s approach to energy trade as a “common denominator for regional peace.” It is clear that Turkish government openly associates the country’s political and economic stability with its regional energy-related interests. In addition, Turkey has set the ambitious target of becoming an energy hub, not only to generate additional revenue, but also to acquire more geopolitical influence in the region. Turkey is trying to assert itself across the swath of Iraq, Syria and all the way to Libya, with its eyes set on having power not seen since the Ottoman Empire more than 100 years ago.

Shortly before passing laws that allow Turkey to send troops and proxies to Libya, and before sending the first group of troops to back the Tripoli government, Turkey’s state-run Anadolu Agency published a document, written by foreign policy analyst Mehmet A. Kanc, that amounts to the announcement of an official new geopolitical strategy cum. justification for its interference in the eastern Mediterranean and Libya. Ankara’s plans for the region, as defined in the Andolu document run as follows:

Turkey’s new defense territory covers on the one end the west and south of the Greek island of Crete and the headquarters of the Turkey-Qatar Combined Joint Force Command overlooking the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf and the Somali Turkish Task Force Command in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, on the Indian Ocean coast on the other. Turkey now wants to strengthen its defense line with a new link in Libya.

For anyone looking to interpret Turkey’s moves in that region, this commentariat should be the beacon. Aside from asserting political, military, and economic interests on the basis of Ottoman-era borders, and laying claim to vast maritime territory from Cyprus to Somalia, Ankara is asserting an ideological supremacy that reflects steps it has been taking elsewhere.

Turkey’s claims to eastern Mediterranean and Libya in the manifesto of its naval and geopolitical strategy follow from this “ideological defense line” against the Saudi presence and influence in the Levant and in Africa, where Ankara seeks to displace Riyadh-led Islam with its own religious and humanitarian leadership (see: “The Ottoman Empire Strikes Back?”).

Turkey’s moves is a gradual effort to entrench its demands in the Eastern Mediterranean and to test the resolve of parties with interests in the region. In its effort to find alternative energy sources for its internal consumption, as well as for the realization of its strategic aims to become a significant peripheral stakeholder, Turkey strives to subverse the current status in the region with high risk actions and statements.

More than anything, Turkey’s entry into the Libyan conflict, posturing off the coast of Cyprus and the eastern Aegean, are an indication of the lengths to which Ankara is willing to go to prevent the emergence of a new order in the Mediterranean. Turkish escalation is designed to make it unprofitable -politically, diplomatically, and commercially- to attempt to ignore or exclude Turkey’s interests.

If anything, those who observe Turkey today should take it into account, with the perspective of what the duo of Erdogan and Bahceli -backed by some staunchly expansionist radical officers- envision for the country in 2023, its centennial as a republic.

The goal is “Turkey made great again”, with the aspiration to control a key global commerce route that connects the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean Sea; that is Asia with Europe through the Red Sea, the Suez Canal and North Africa. Turkey’s presence in Libya and its large military base in Somalia serve precisely this ambition. Turkey does not just want to control the southern gateways to Europe, but also influence political developments inside Europe; it does that both through the presence of Turkish migrants in countries like Germany, and the exploitation of refugees in threatening to cause a new migrant crisis.

Energy relations with Russia

Energy demand has been one of the main burdens on the Turkish economy, with Ankara paying tens of billions of dollars annually to meet the country’s energy need. Relations between Russia and Turkey, once Moscow’s biggest consumer of natural gas, have been patchy for the past years and are beset by a number of issues, including conflicts in Syria and Libya.

Russia was Turkey’s top gas supplier in March last year but as its sales dropped as much as 72% it now ranks as the fourth-biggest supplier, according to Turkey’s Energy Market Regulatory Authority. Since prices for Gazprom’s gas are several times higher than for liquefied natural gas (LNG), imports are booming from the United States and through the Transanatolian Pipeline (TANAP) from Azerbaijan.

Energy giant Gazprom is rapidly losing Turkey, once considered one of its most promising and largest markets, from 2008 to 2014 when the demand for gas in the country grew by 30%, due to the company’s high prices. While the price of gas exported by Gazprom to Turkey’s Petroleum Pipeline Corporation (BOTAS) was around $228 per 1,000 cubic meters in the second quarter of the year, spot gas prices in Europe fell below $100 in the same period.

The extension of contracts for 8 bcm of natural gas with Gazprom expires in 2021, while the market situation allows Turkey not to renegotiate them, which could leave the recently built TurkStream gas pipeline half empty.

Turkey is looking to reduce further its reliance on Russian gas, and for the first time in almost two decades, Turkey may not receive gas at all from Russian gas giant Gazprom for at least two weeks.

According to Turkish state-owned BOTAS, the TurkStream pipeline stoped completely on July 27. BOTAS is the purchaser of all gas through the pipeline, which started up this year in January. The pipeline was to remain down for a couple of weeks until mid-August due to repair work on the pipeline. The other gas pipeline from Russia to Turkey, the Blue Stream, was also shuttered in May, and even though it was only supposed to be down for a couple of weeks, the pipeline is still shuttered today. From its part, Gazprom has not commented yet when Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines are set to be re-launched, as well as whether BOTAS would face fines due to the pipeline’s suspension and lack of offloads by the Turkish company. BOTAS and the Turkish Energy Ministry remain silent too.

In the end, Turkey is taking 70% less gas from Russia compared to this time last year, pushing the gas giant down on the list of Turkey’s main gas suppliers, behind Azerbaijan and Iran. Turkey has also been substituting LNG for the Russian gas, now that LNG prices have fallen. It plans to buy at least 1/3 of its needs this year in the form of LNG to replace the more expensive fuel from Russia, with cargoes coming from the United States, Nigeria, Algeria, Qatar and also Russia.

On August 21 Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that the Fatih drilling vessel discovered the country’s largest energy source in its history -320 billion cubic meters of natural gas in the Black Sea. The discovery is projected to ease the financial burden for a number of years, as President Erdogan said authorities were planning to have the natural gas reserve ready for Turkey in 2023. The discovery is not likely to end Turkey’s dependence on foreign alternatives but he said the reserves found were “only part of much richer resources”, given the fact that Turkey has one of world’s top drilling and seismic operation fleet and also holds operations in the Eastern Mediterranean.

However, despite the triumphant tone of the announcement, the markets have not reacted well. Shares in Turkey’s Tupras refinery and petrochemicals company Petkim have seen a steep fall. Experts say the highly optimistic predictions for the new Sakarya gas field are only preliminary and leave unanswered questions about whether the natural gas can be fully extracted or whether the announcement was geared towards President Erdogan winning back public support.

A three-year deadline for a start-up date appears too ambitious. Such a deadline would require a world-class and near-unprecedented project execution, a difficult feat considering Turkey’s lack of experience in deep-sea gas production.

MAVI VATAN: “Mare Nostrum”

The coining of the term “Mavi Vatan” (Blue Homeland) ultimately represents more than an act of political branding. Within the framework of Turkey’s new energy (in)security architecture owing to the emerging trilateral partnerships in the Eastern Mediterranean, which it feels threaten its own efficient exploitation/transmission of the gas discoveries, Ankara is increasingly anxious. As a result, it is clear that Turkey has adopted the strategy developed by arch-nationalist army officers. As a first step, this new doctrine envisages the domination of the Aegean Sea, of most of the Mediterranean and of the Black Sea. To this end, Turkey has invested in expanding both the size and sophistication of its navy, as well as it drillships and exploratory vessels. This highlights the extent to which Turkey has strengthened its military under the ruling AKP, which has been in power since 2002.

What the “Mavi Vatan” turn means for the future of Turkey’s participation in NATO, or Ankara’s relationship with its Western partners, is far from clear. There are, however, two real dangers ahead: The first is a possible confrontation with Greece which, like Turkey, has been a member of NATO since 1952. The “Mavi Vatan” doctrine makes it clear that Ankara does not recognize the Lausane Treaty’s arrangements over the Aegean. Turkey claims many Greek islands and Greece’s EEZ. There have been threats about drilling for gas near the Greek island of Crete and Kastelorizo. Flushed with confidence after his victories in Syria and Libya, President Erdogan has remained steadfast in spite of threats of sanctions and increased diplomatic isolation. It is possible that he may well decide this is a good time to challenge Greece, especially as such an exploit would play well at home.

The second danger lies in Libya: arguably the most striking demonstration of “Mavi Vatan” worldview can be seen in Turkey’s evolving policy towards it. Turkey has its own ties to Libya, and economic and geopolitical interests that go beyond this regional competition (see:Will Turkey dare to dissolve NATO’s Southern Flank?). Turkey has two goals on Libyan soil: firstly, stopping the Egyptian, Emirates and Saudi operations against Turkey’s economic and oil expansion in the Mediterranean. The other Turkish policy line is that of perceiving a threat of the strategic partnership between Israel, Greece and Cyprus -to which at least it reacts- with the US and probable EU support which, if any, would probably bring obstacles to the Turkish expansion in the Mediterranean.

Turkey is seeking to reap the rewards from its intervention in Libya to bolster its faltering economy, as its backing of the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) in the country’s civil war, puts Ankara on top of the list to bid for multibillion dollar contracts. Turkish businesses say they are looking forward to playing a key role in the rebuilding of the oil-rich North African country. Turkish officials have made trips to Tripoli to meet GNA officials to discuss cooperation in areas such as construction and energy. There is going to be a big business opportunity of around $50 billion.

Consequently, Turkish economy will get a significant boost once the security situation improves in Libya and Turkish firms can start working there. “Al-Arabiya Net” reported recently that the Governor of the Libyan Central Bank, Al-Siddiq Al-Kabir, has deposited $8 billion in Turkey’s Central Bank for about four years without interest, to help stabilise the Turkish lira. Moreover, Turkish officials have made several trips to Libya in recent months to discuss energy cooperation and investments, as well as security issues.

How Turkey got Libya through “crisis of the month” strategy:

The more invasions, the more Ankara is the go-to country for all conflicts in the Middle East. This has been accomplished through Ankara’s carefully executed policy of stoking a new crisis each month to get what it wants. Crisis-a-month is how Ankara is able to get the US, EU, NATO, Russia and Iran to all value Turkey more than they seem to want to work with other countries in the Middle East. Turkey accomplishes all this by heating up different conflicts each month and then demanding concessions. Ankara sells itself as the key to every conflict in the Middle East by first invading and then claiming it can solve the conflict. Libya is the jewel in the crown. The aggressive survey of Oruc Reis in Eastern Aegean is of paramount importance too.

Turkey uses these crises to pressure Europe, Egypt and Greece for concessions and also to work with Russia and USA at the same time. Ankara has also shown that the Arab states, despite their complaints about its continued escalation, are largely unable to stop Turkey and will continue to be distracted by the numerous crises that it heats up every month.

A short while ago, the President of the Presidency Council of the Libyan Government of National Accord, Fayez al-Sarraj announced his intention to step down from his post at the end of next October. This decission was not welcomed by President Erdogan. His obvious annoyance piqued the curiosity of political observers, who attributed that anger to either the political dimension of Sarraj’s decision or its economic significance. It is common secret that for Turkey President Sarraj’s power to sign economic agreements, was very important. Some observers suspect the existence of economic understandings, most likely, between Sarraj and Ankara that have not been implemented yet and they do not exclude the possibility that they could be related to the ports, especially the port of Misrata.

Moreover, Turkish officials have already confirmed that there were talks with the Libyan authorities about starting oil and gas exploration operations in onshore and offshore fields, in addition to talks about other energy-related fields such as electricity production.

In the event of Sarraj stepping down before Ankara could secure guarantees for the implementation of its future projects, Turkey will be forced to start all over again with the next government.

Al-Watiya’s airstrikes uncovered Ankara’s inefficiencies…

This bombardment was of operational importance because it was a major blow to the Turkish Armed Forces. The attack on al-Watiya can be seen as a test to gauge the capabilities of the Turkish air defense system in Libya. The system failed the test, which indicates that the area south of Tripoli is not under full aerial control of Turkey, and that the air space dominance over the region is contested. The biggest disaster for Ankara, however, was on the political level. For the first time Turkey got paid back in the same currency it’s using, sending Ankara the message that from now on it will receive such retorts. And this message was received not only by Ankara, but also by all the rest stakeholders in the region. It is no coincidence that President Erdogan did everything he could to downplay the incident. The conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque was probably hastened, precisely to cover up the event communication-wise and to balance the political blow from al-Watiya (see: “Al-Watiyah’s hit exposed Turkey’s limitations…”).

Despite this setback, however, Turkey seems determined to press-on to attempt to occupy Sirte and al-Jufra. In this endeavor it can only count on Qatar. Russia recognizes Ankara’s important role in western Libya, but opposes turning all of Libya into a Turkish protectorate. In essence, the Kremlin is seeking a compromise on its conflicting interests with Turkey in Libya, as has happened in Syria. This is because for Presidetn Putin the “big picture” is far more important; that is, to achieve a deeper chasm in NATO’s Southern Flank by enstranging Turkey all the more to the West. That is why he took down his Orthodox banner on the issue of Hagia Sophia, speaking of an “internal affair of Turkey.” The Moscow Patriarchate was left to let fly barbs against President Erdogan (see: REPORT #5 NATO in Eastern Mediterranean: The Haze of Energy War…).

In the mind of Recep Tayip Erdogan

Domestic economic and political considerations are certainly at play in President Erdogan’s aggressive foreign policy, with public disquiet over Turkey’s struggling economy brewing and the strength of the political opposition building, while COVID-19 reaps unknown numbers of lives. His regime needs constant action to hide what is happening really inside the country, and it is very happy to see discussions about the victorious Turkish army running around the world, as a distraction.

Turkey’s economy on the verge of collapse

Inescapable as death and taxes, with the arrival of autumn Turkey has plunged into its cyclical currency crisis. This time, however, the epilogue could be different from that of 2018 and especially last year, when it was the billions of Beijing -headed by an old swap miraculously went to the collection with Swiss punctuality- to save the Ankara Central Bank from the bleeding of its foreign reserves in an attempt to defend the lira from speculative attacks.

Today, in fact, not only the country is in far worse financial conditions than those of the recent past but, above all, Covid-19 has brought the tourism sector to its knees, one of the few that can guarantee tax revenues. In short, the strong risk is that Turkey will fall into a state of absolute instability.

Inflation and external vulnerabilities remain high in Turkey, made worse by currency weakness, while the economy is expected to contract this year. Concerns among investors about policy direction and transparency have resulted in further depletion of the central bank’s foreign currency reserves this year, increased dollarisation of the economy and a weaker lira.

To make matters worse, credit rating agency Moody’s downgraded Turkey’s debt rating to “B2”, warning of rising geopolitical risks as factor for the new rating, as well as the foreign currency long-term deposit ratings of 12 banks, the long-term counterparty risk ratings (CRR) and the long-term counterparty risk assessments (CRA) of six banks, and the long-term senior unsecured rating of one bank by one notch and the long-term foreign currency CRR of three banks by two notches. The credit rating to “B2” from “B1” puts Turkey on par with Egypt, Jamaica and Rwanda.

Fitch ratings agency following suit, downgraded also the outlook on Turkey’s Long-Term Issuer Default Ratings (IDRs) to negative from stable and affirmed the IDRs at “BB-“.

The revision of the outlook was mainly due to Turkey’s depletion of foreign exchange reserves, weak monetary policy credibility, negative real interest rates, and a sizeable current account deficit partly fuelled by a strong credit stimulus -which have exacerbated external financing risks, Fitch said.

Turkish economic activity has slowed sharply after investors pulled out of the country on fears that the economy was overheating.

President Erdogan is the master of creating crisis, using the weaknesses in his antagonists, duping rivals, employing divide and rule policies. It seems that mr. Erdogan saw the 4th anniversary of the attempted coup as a symbol for launching a series of acts that aim to cement his power. Above all, his equation is simple: in order to survive politically, he has to constantly raise the stakes in a daredevil gamble. He may or he may not, however, the Turkish President is focusing on headline-grabbing issues, in an attempt to captivate the minds of his electoral base. The only thing likely to erode that base of support would be a large number of Turkish personnel killed in his overseas adventures.

The move to turn the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque, against all odds, signals plans for a snap election. Turkey’s strongman U-turn from his last year’s opposite stance, points to uncertainety, to say the least, ahead of the next general elections scheduled for 2023. Polls increasingly show Turkey’s new political parties founded by former Erdogan allies, eating away at the support his ruling AKP had.

President Erdogan’s declaration is meant to serve as a national boost at a time when Turkey is in an extremely precarious political and fiscal position. Turkey has waded into the Syrian quagmire, it has the Kurdish problem to contend with, it is conducting risky adventures in Libya, and it is stirring unrest in the Eastern Mediterranean. In Erdogan’s view, turning Hagia Sophia back into a mosque is a Turkish victory and a source of national pride during a time of great turmoil.

To Erdogan, Hagia Sophia is evidence of Turkish Muslim hegemony over the Muslim world. Its transformation into a mosque emphatically declares that position. Is the timing of this move with the anniversary of the aborted July 2016 coup accidental?

All the more, in order to gain more time, “good news” like the one from the gas discovery in the Black Sea come in handy. The announcement continues the diversionary strategy. But there is still a lot of time until 2023. Maybe more than mr. Erdogan is still on diversions.

The fact of the matter is, the foreign policy he has helped shape will offer more problems than solutions in tackling the current world, as well as Turkey’s, disorder. He has been squandering Turkey’s almost 70-year-long accumulation of diplomatic capital, including its strategic alliances, international prestige and its progress in long-term geopolitical aspirations. President Erdogan calls it “forward defence” -fitting the policy line his partner Bachcheli has been advocating all along- and coins another key expression: “Military first”. The trio of traditional Turkish military might, its recent technological advancements (drones, airlift capabilities, professionalised army, its modernised fleet) and effective use of Islamist fighters in the form of mercenaries or as proxies, proved a formidable force in overturning the balance of forces on the ground. Turkish victories in Syria and Libya, however, have been made possible mainly by Washington and Europe’s unwillingness to stand up to mr. Erdogan, which only feeds his sense of invincibility.

Turkish supplies of weapons and military equipment to Libya in violation of the UN-imposed arms supply embargo include of BMC Kirpi II, BMC Vuran and ACV-15 armoured vehicles, T-155 Firtina self-propelled howitzers, Oerlikon 35 mm towed anti-aircraft guns, KORKUT self-propelled air-defense gun systems, MIM-23 Hawk low to medium altitude ground-to-air missile systems, AN/MPQ-64 Sentinel radars, and 9K11 Malyutka anti-tank guided missiles. These weapons are supplied to the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord or directly used by Turkey forces to support it in its battle against the Libyan National Army.

Nevertheless, the purchase of the Russian S-400 air defence system has been proved the most ineffective arms procurement in Turkey’s defence history. The move has deprived Turkey of the 5th generation F-35, while the $2.5 billion S-400 systems are kept in deep-freeze. Even if and when S-400s are activated, they will only function at a very small percentage of their capacity because they can’t be connected to the electronic surveillance network in Turkey.

On the other hand, there are now reports that Greece is in negotiation with the United States to purchase F-35 jets, along with others that say the UAE is inching closer to a similar agreement. Greece is in also talks with France to purchase the Rafale aircraft. With these procurements, the military balance in the Aegean will most probably tilt in Greece’s favour, especially at a time when Turkey is deprived of the F35.

CHINA offers Erdogan a lifeline for his politico-economic troubles

China and Turkey have signed 10 bilateral agreements, including on health and nuclear energy, since 2016, according to the Turkish parliament’s official website. Furthermore, Peking intends to invest $6 billion in Turkey by 2021, doubling its investment made between 2016 and 2019.

The strategic partnership between China and Turkey give Turkish President Erdogan a lifeline for his political and economic woes. Strengthening Sino-Turkish relations appears to benefit both sides. China has found a highly strategic foothold in Turkey: a NATO member with a large market for energy, infrastructure, defence technology and telecommunications at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and Africa.