Turkey advances in Libya humiliating U.N. and E.U. resolutions

Anastassios Tsiplacos - Managing Editor

Recently we heard of an Hellenic Navy’s vessel, participating in the EUNAVFOR MED “Irini” to uphold the United Nations-imposed arms embargo on Libya, which was monitoring the movements of a Tanzanian-flagged Turkish ship suspected of carrying military equipment (weapons, ammunition and other items) to Libya. The Tanzanian-flagged cargo ship “Cirkin” was accompanied by three Turkish frigates and was sailing southwest of Crete in the direction of northwest of Benghazi, 150 nautical miles from Tripoli.

The European services that coordinate the “Irini” Operation had been alerted of the cargo ship, accompanied by three Turkish frigates. The Italian commander of the European operational force ordered the Hellenic Navy’s frigate “Spetsai” that was sailing between Crete and Libya to approach the suspicious ship.

At around 6 a.m. on June 10, the Hellenic Navy’s Sikorsky S-70B helicopter flew over the suspicious cargo ship and requested the crew’s cooperation to a VBSS (Vessel Boarding Search & Seizure) operation on the basis of the mandate of the Operation “Irini”. There was no response from the cargo ship to the repeated calls from the pilots of the Greek helicopter. A few minutes later, one of the three Turkish frigates responded that the ship was under the protection of the Turkish Republic. In this way, the Turks refused the VBSS operation, indirectly confirming what its cargo really is.

So, the frigate “Spetsai” was ordered to discreetly monitor the course of the cargo ship as it approached the shores of Libya. There was just one Operation “Irini” vessel monitoring a huge area between Crete and Libya. Turkey, however, appeared to have a total of eight ships in the area, including the suspect vessel and the three frigates.

Commenting on the incident, EU’s High Representative Josep Borrell, said that Irini personnel tried to make contact with the “suspicious” Tanzanian-flagged which refused to respond, but its Turkish escorts declared the cargo was medical equipment bound for Libya. He also said the personnel contacted the Turkish and Tanzanian authorities to try to verify the information, and they also informed the United Nations. “We cannot do anything more than to transmit this information to the United Nations. It is the United Nations who gathers this information in order to control the implementation of the arms embargo. It is only in the cases in which the ship is not answering that we can take another kind of activities.” mr. Borrell said, however he refused to elaborate.

In late May, USAFRICOM reported that at least 14 MiG-29s and several Su-24s were flown from Russia to Syria, where their Russian markings were painted over to camouflage their Russian origin. These aircraft were then flown into Libya in direct violation of the United Nations arms embargo.

“We know these fighters were not already in Libya and being repaired,” said Col. Chris Karns, director of USAFRICOM public affairs. “Clearly, they came from Russia. They didn’t come from any other country.” Russia’s introduction of manned, armed attack aircraft into Libya changes the nature of the current conflict.

A few days before, we read that Turkey deployed an unknown number of the U.S.-made M60 main battle tanks to Libya in support of its ally, the Government of National Accord (GNA). According to Turkish sources, a convoy of low-bed trailers were seen transporting several M60 tanks in the vicinity of the Libyan capital, Tripoli.

For some time now, Turkey has consistently transferred several combat systems to the GNA, such as the Kirpi armored vehicle, which has failed to make a strategic impact to the conflict, and has even been judged combat ineffective by the LNA after several were captured and tested.

Although, it is not yet known if the tanks sent to Libya are the legacy M60 model or the vastly improved Sabra MK II variant, Turkey has likely sent trained personnel and crews to man the M60 main battle tanks as the GNA currently lacks the capacity to effectively operate them.

M-60T (Sabra Mk.II upgraded)

The Turkish Armed Forces owns more than 1,500 M60 Main Battle Tanks (MBT). Most of these have been upgraded by Israel’s IMI Systems to the Sabra Mk II standard.

Turkish Sabra MK II MBT is fitted with modular passive armour protection, which is upgraded to explosive reactive armour. It also includes an all-electric gun control system.

The tank is equipped with a Knight computerised fire control system supplied by El-Op (Electro-Optics) Industries Ltd.

The above incidents, and many more not widely known, indicate that the so-called EU’s Operation “IRINI” is not so adequate and/or willing, to fulfill its main mission to uphold the United Nations-imposed arms embargo on Libya. More on this later…

Why Libya’s civil war lingers…

Libya holds Africa’s largest crude reserves, according to the Libyan Petroleum Institute responsible for the extraction, refining, and export of petroleum. However, nine years of conflict and violence in the country since the 2011 ouster of ruler Muammar Gaddafi have hobbled production and exports. Till 2014, the North African country on the banks of the Mediterranean Sea was ranked among the top 20 oil-producing countries.

Libya is a sprawling chaos, and not just because of the fighting between Haftar’s LNA and the UN recognized government in Tripoli. Nor is it because of the scores of private/tribal/jihadist militias that terrorize what is left beyond the territories not controlled by Haftar and the Tripoli government. Libya, has become, like Syria, the battlefield for a proxy war between opposing forces that are now embroiled throughout the Middle East, the Gulf, and the Maghreb. The lines that were first drawn years ago when the so-called “Arab Spring” destabilized regimes throughout the region and led to the mess we see today, linger…

In the after COVID-19 era, the Libyan civil war continues to be a highly complicated geopolitical issue of extremely significant economic importance to Europe, and there are already many stakeholders involved. So many that it is difficult to come to an agreement. Some of those stakeholders seem to have an unstated but clear interest in controlling the energy flow to Europe for political gain.

The new adversaries, of course, include the USA and Russia. Siding with Russia, at this point are Syria, Iran, while Turkey and Qatar are courting and being courted by this group. The US has a staunch ally in Israel, strong allies in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. It has been a much more vocal and active supporter of Greece and Cyprus, and there is renewed cooperation with France.

The EU strives to find a coherent position, while at the same time is trying to remain in the picture of the Libyan crisis as a primary actor.

The UK is mired with all the after COVID-19 shock and Brexit business and has interests in maintaining a shadowy condition as a “guarantor” power for Cyprus.

China has its own problems with the US in another part of the world, and in this theater is just biding time.

As the UN continues to hold various unsuccessful rounds of negotiations, the original constellation of outside actors funneling money and weaponry to rival groups within Libya -in violation of a its Arms Embargo- underwent certain modifications.

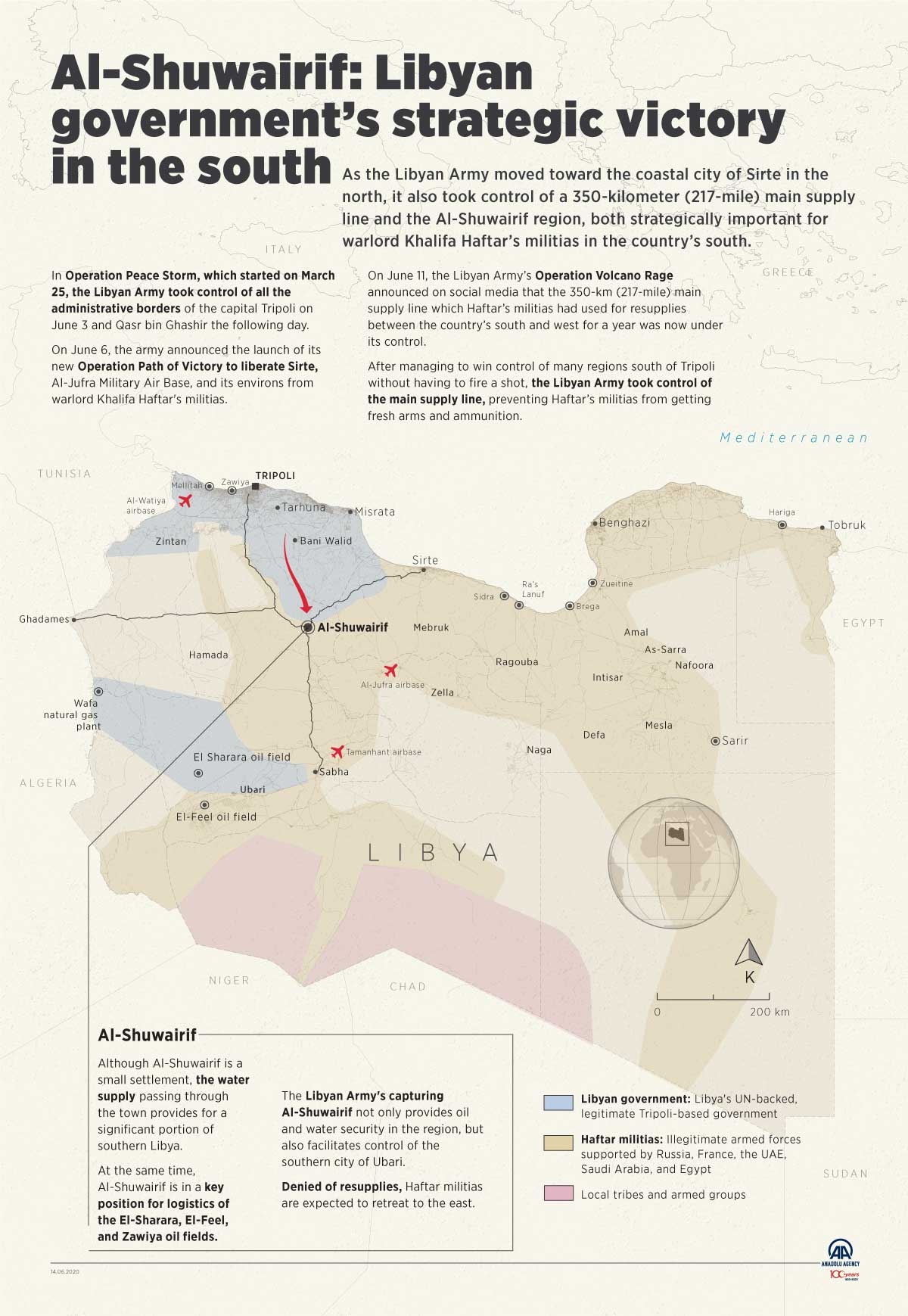

The Libyan problem has an important impact in the European Union as Libya is a major oil producer of sulfur-free crude. In this context, on January 17, just the day before International Berlin Conference, Ibrahim Cadran’s armed group called “Petroleum Facilities Guards” affiliated with General Haftar’s LNA, closed oil facilities in Sidra, Ra’s Lanuf, Briga, Zueitine, and Hariga, seizing large export terminals, including El-Sharara and El-Feel oilfields, to cut off major pipelines aiming to choke the UN-backed government of significant revenue. The oil production activities of Sharara and El-Fil oil wells in the south of the country had been earlier stopped by these groups in February 2019.

The production in the area accounts for 60% of oil exports. Libya’s state National Oil Corporation (NOC) recently announced that for the period 2016-2019 oil exports were down by 92.3%, losing more than $100 billion since the country’s oil blockade. Libya’s cumulative losses from January’s oil blockade have neared $5 billion. While international energy institutions say that most of Libya’s oil reserves have remained untapped, the conflict has hit extraction of oil from the existing resources.

Oil lifeline for the Libyan economy

Since the discovery of oil in the second half of the 19th-century oil revenues have been the lifeline of Libya’s economy. Libya’s hydrocarbon resources used to meet the demand of around 70% of national expenditure. As much as 93 % of the government revenues and more than 90 % of exports were met by oil revenue until Muammar Gaddafi regime was overthrown in 2011.

In 1970, Gaddafi had moved Libyan Petroleum Institution from the eastern town of Benghazi to the capital Tripoli in the west of the country. It reduced the influence of eastern regions, which has approximately 80% of the country’s oil reserves.

Specifically, El-Sharara oilfield produces more than 300,000 barrels of crude oil per day, forming roughly 1/3 of the oil-rich country’s production. The Sidra refinery can produce 350,000 barrels of oil per day. The daily production capacities of other refineries like Ra’s Lanuf are 220,000 Zueitine 100,000 and Briga 8,000 barrels.

The collapse of the Gaddafi regime allowed the eastern political groups to rally around and take control of the oil sector. Riots erupted against Gaddafi in Benghazi, where people were seething with anger for shifting the petroleum institute.

The country had recorded the production of 1.6 million barrels of oil in 2010, which dropped significantly due to instability and different groups fighting to take control of resources. Finally, Haftar’s militias made the situation much worse in the region. Since 2014, Haftar’s militias have been targeting the oil fields to strengthen their position in the ongoing war.

The country’s Central Bank has reduced its reserves to the lowest level in its history to meet the requirements of paying salaries to government employees and basic expenditures on food, health, and education. The lack of finances has led to severe economic crises in Libya. The country is facing high inflation, depreciation of the local currency, and the rise in public debt.

Last month, El- Sharara oilfield, the country’s largest, restarted production, the National Oil Corporation (NOC) said. “We hope that resuming production in the El-Sharara field will be the first step to restore life to the oil and gas sector in Libya, and a start to save the economy from collapse.” Nevertheless, while it looked like Libya was on track to bring its oil production back online, it has since become clear that the war for control of its oil is far from over. General Hafar, having lost the battle for Tripoli, sent his militia forces to shut down Libya’s two largest oil fields again.

Nowadays, the bone of contention is the port city of Sirte and al-Jufra airbase in the central region. Sirte is adjacent to the so-called “oil crescent” comprising Libya’s key oil terminals, and the GNA and Turkey intend to gain control over them.

Hydrocarbons are the pivot in this issue, as it is in this whole conflict. All the stakeholders are hydrocarbon producers, or wanabees. At a first glance, hydrocarbons permeate the playing field. Crises in these hydrocarbon producing regions, in many ways rule the world. All major players are Oil and NG producers, and their proxies “sit astride” transit routes, or dream of the conquest and piracy of the sources of others, who are more than willing to taste the plunder.

Libya’s civil war and Turkey’s Presence in Tripolitania

The Mediterranean is the natural end of the Chinese project of the “New Silk Road.” It is also the point of contact between Europe and the Arab world. The Mediterranean region is also the axis of the new economic and strategic Israeli expansion, as well as the unavoidable channel of connection with Africa, which will be at the core of the already easily predictable geoeconomy of the near future.

We should also note the new U.S. posture towards the Pacific to encircle China and hence the relative decrease in the U.S. pressure on the Mediterranean region.

The Eastern Mediterranean epitomizes the shifts in the global order: American retrenchment, coupled with the continuing ineffectiveness of the European Union, has created space for local actors to engage in hard-power politics. This has worked in Turkey’s favor–for now.

Nowadays, those who give the cards in the Mediterranean are Algeria, Egypt, Turkey, as well as obviously the Russian Federation and China. When the cats are away, the mice will play. Even the oil and gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean region change many of the current economic and political games and trigger new alliances.

Greece, for example, has officially and recently announced it cannot rule out the use of force in a possible conflict with Turkey. Just think that they are two NATO countries (see: REPORT #5 NATO in Eastern Mediterranean: The Haze of Energy War…).

As shown in a note drawn up jointly by Turkey and the Libyan GNA, what is at stake here are the 24 new blocks for oil and gas exploration existing in a region that would deprive Greece of some Dodecanese areas and would almost completely close the Aegean Sea, thus making it a strategic object in Turkey’s hands (see: Turkey plans an “Energy Invasion” in Eastern Aegean Sea…).

Currently a proxy war is being fought in Libya: Turkey and Qatar against Egypt, UAEs and Saudi Arabia, who want everything but Turkish hegemony over Libya and vice versa. Libya, however, must be considered within the framework of a set of political, economic and military relations that are now very broad and concern the interconnection between Libya and Africa, including sub-Saharan Africa.

The EU has allowed the permanent and stable crisis of the Libyan territory, after a hammering and manipulative series of trivial defamation operations against Gaddafi and his greatest ally, namely Italy. There is also the hypothesis, which is now even more than a hypothesis, that Turkey would like to build military infrastructure together with NATO in Southern Libya, which would be the real game changer of the current balance of forces on the territory. In recent months, Turkey has brought 9,600 mercenaries to Libya and other 3,300 ones are training in Syrian camps. Certainly Italy, too, will participate in this operation, within the framework of the Atlantic Alliance, but only to play second fiddle compared to Turkey, which has no interest in having Italy as a partner, neither economically nor militarily, and certainly not in Libya.

Turkey Turns the Tide in Libya?

Turkey’s military intervention in Libya has recently enabled a series of victories for the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), to the detriment of Khalifa Haftar and his backers in Cairo, Abu Dhabi, and Moscow. The reversal of fortune for the GNA, which forced mr. Haftar to propose a ceasefire, marks a major shift in the trajectory of the Libyan civil war and will likely cement Turkey’s role as a key arbiter in the ultimate resolution of the conflict. Should the recent developments prove durable, Turkey will exert significant influence in the North African country.

Faced with a consortium of rival countries –Greece, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt– all intent on capitalizing on the off-shore energy resources in Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey last year launched a strong counteroffensive. In November 2019, Turkey and the GNA signed a military Memorandum Of Understanding. Contrary to other outside actors operating covertly in Libya, the Turkish Parliament openly voted to approve a one-year mandate for military assistance to the GNA, and in January 2020 Turkey declared it was deploying troops in the country. Since then, it has also employed a growing number of mercenaries from Syria to fight in Libya; estimates are of at least 100 Turkish officers coordinating the GNA military campaigns alongside thousands of Syrian mercenaries. Over the last several months, Ankara has also used its Navy and Air Force to assist the GNA, and the most notable effect in bolstering the GNA’s military efforts has come from the use of its drones over Libya.

In parallel to the November 2019 military agreement, Turkey and the GNA signed a maritime delimitation agreement, which underscored Ankara’s desire for an extensive continental shelf in Eastern Mediterranean.

Turkey’s efforts to assist the GNA should be understood in the broader regional context. Ankara’s growing sense of isolation in the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as its tense relations with the UAE, propelled it to raise the stakes in Libya. Its relationship with the GNA, and the maritime delimitation agreement in particular, aims to obstruct plans to build the EastMed pipeline, which was slated to export natural gas from Israel though Cyprus and Greece and on to Europe.

Turkey also acted decisively off-shore, by obstructing the exploration of gas by private companies in the contested zones of the Mediterranean and launching its own exploration missions. The government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has won popular support at home for this posture, which is part of its “Blue Homeland” doctrine calling for a more aggressive defense of Turkey’s off-shore sovereign rights.

By obstructing developments inimical to its national interest, Turkey has demonstrated its ability to be a “veto” power in the Eastern Mediterranean. But to capitalize on its strategic gains Ankara should now prioritize multilateral diplomacy, or risk being mired in regional conflicts. The danger is that mr. Erdogan, buoyed by these early gains, will invest even more resources in hard-power tactics, at the expense of coalition-building and diplomacy. This would only harden anti-Turkey alliances, on land and off-shore.

Hence, what does Turkey want from al-Sarraj’s Libya? First and foremost a primary economic and strategic role in the future Libyan reconstruction. Secondly the autonomous drilling of the above stated oil maritime areas in the Eastern Mediterranean region, disputed between Turkey, Greece and Cyprus. The GNA has long authorized the Turkish Petroleum Company to carry out exploration in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Should the GNA ultimately gain control of Libya’s oil facilities -which remain largely under Haftar’s forces- Turkey would reap substantial economic benefits, as it lacks energy resources of its own and would likely secure lucrative contracts for Turkish companies to assist in Libya’s reconstruction. Last month, Turkish Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Fatih Donmez said Turkey may start oil exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean in three or four months, “within the framework of the agreement reached with Libya.”

The success of Turkey’s latest gambit is by no means a foregone conclusion, given the myriad twists and turns of Libya’s post-2011 trajectory, and the possibility that pandemic-related economic woes could force Ankara to temper its ambitions.

Turkey’s ability to maintain a durable presence in Libya signals its dominance among the outside powers seeking to influence the sparsely populated but oil-rich nation, since longtime dictator Muammar Ghaddafi was ousted in 2011.

In view of having a base shared with al-Sarraj’s Navy, the ideal base for Turkey is certainly Abu Sitta. Nothing to do with the usual complaining by Italy, always waiting for an agreement that will never seriously come with Tripoli’s Navy. In Abu Sitta, in fact, an Italian military ship is at anchor, which coordinates, with 70 soldiers, the work of the Libyan Coast Guard to fight against illegal migration. Who will be heard more in Tripoli, the Italian government or Turkey’s new neo-Ottoman imperialism? The answer is very easy (see: The Othoman Empire Strikes Back).

The Tamenhant Airbase scenario

The recent meetings of the Turkish ministerial delegation with the al-Sarraj government of the Turkish field officers in Libya revolved around determining zero hour for the launch of a military operation that will certainly go beyond what has so far been announced, which is to first take the city of Sirte, then move to expand to the area of the oil crescent.

According to Libyan military sources, the Turks want to control the Tamenhant airbase in south-western Libya in order to make it a crucial hub for further aggressive moves. Controlling that base would pave the way for taking control of Libya’s major oil fields, especially the Sharara field and El-Feel field in which Russian energy giant Gazprom holds a stake of one third.

Tamenhant Base is located 30 km northeast of the southern city of Sebha and about 750 km south of the capital Tripoli. It is one of the most important military air bases in the south of Libya, covering an area of 35 square kilometres. Its strategic location overlooks the road linking Sebha and the Al-Jafra region in central Libya and linking the cities of the Libyan south to the north of the country.

In 2017, Haftar’s LNA took control of Tamenhant Base. The base includes an operational runway and aircraft maintenance workshops, which make it no less important than Αl-Watiya Base which was recaptured by the Turkish-backed al-Sarraj government militias in March.

The real purpose of pushing more Syrian mercenaries in the southwest is to gain control of the Tamenhant airbase to cut it off from the armed forces present in Jafra, Sirte and Burqan al-Shati. The Turkish military realise that controlling the sources of oil exports is impossible unless they control their three gateways. The Tamenhant airbase constitutes the southern gateway to the oil fields and terminals.

To the extent Turkey’s intervention elicits heavier Russian involvement in the Libyan arena – as evidenced in recent days by Russia’s deployment of fighter jets to assist Haftar’s forces – developments on the ground could also ultimately draw in greater American engagement. Thus, while for now Turkey has managed to turn the tide in the Libyan war, the implications of Ankara’s recent successes will likely extend far beyond Tripoli’s shores.

The American-backed Turkish ambitions also constitute a threat to NATO, as these ambitions collide with the interests of other member states, especially France. It seems that this shift in the Turkish expansion plan in Libya is the one that has angered France, which sees southern Libya as part of its interests that extend to the rest of the Sahel and Sahara countries, pushing it to intensify its criticism of Turkey’s regional ambitions.

The Russia-Turkey equilibrium

Both Russia and Turkey want to take advantage of a dysfunctional and shrinking European Union, a solipsistic America and a China focused on consolidating power in its own neighbourhood first.

Libya, however, is just one of a handful of touchy subjects for Ankara and Moscow. Russia and Turkey have in the past five years often found themselves in “this halfway point between war and peace”. Moscow backs Syrian President Bashar Assad in his stand-off with Turkey in Syria’s Idlib province, where Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin brokered a March ceasefire.

In the energy sector, a recent report found that in the last two months Turkey has been importing more gas from Azerbaijan than from Russia, despite the two launching the $7.8 billion TurkStream pipeline in January. Moreover, seven Turkish companies are in a large debt to Russian state energy giant Gazprom. The Turkish energy companies accumulated debt of nearly $2 billion after failing to fulfil agreements with the company. The debt in question stems from the 2019 delivery of Russian gas, based on separate long-term contracts with Gazprom, at between $250 and $300 per 1,000 cubic meters. The debt issue could amplify Turkey’s economic concerns risking already tense ties between Ankara and Moscow.

Moscow has sought to expand its influence in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and supported that mission through military escapades. Strengthening the Russian military position in North Africa will undoubtedly provide Russian President Vladimir Putin with a much tighter grip over Europe and possibly even deep-rooted influence and control in the wider MENA region. Libya’s energy resources and the presence of several deep-water ports will give Putin the logistical and geo-strategical advantage he is attempting to achieve.

According to reports, Russia recently transferred more than a dozen fighter jets to al-Jufra. Turkey anticipates that Russia has plans to turn al-Jufra into a military base. The spectre of Russia establishing a military base in Libya also haunts the U.S. and NATO.

Although there is a congruence among Ankara, Brussels and Washington that any moves to establish a Russian military base in Libya must be pre-empted, as that would foreclose NATO’s planned intervention in Libya and future expansion plans in Africa, that apart from weakening the Alliance’s dominance while Russia strengthens its presence in the Eastern Mediterranean and challenges Turkey’s historical pre-eminence in the region. Nevertheless, there are various estimates which support the notion that there is already a pact between messrs. Erdogan and Putin to guarantee only to Turkey the Al-Watiya base, which would become -also with Russia’s agreement- a base shared by Turkey and the U.S. AFRICOM.

Much of the effort by the GNA appears to have been accomplished without major fighting and there are hints of a secret deal or a compromise of sorts that has been made by the backers of both Haftar and the GNA. These allegations are based on experts’ observations that the withdrawal of Haftar’s air forces from al-Watiya was already being negotiated between the two sides, as well as his land forces, had already left Bani Walid, again without firing a shot. The way mines were laid by Haftar’s LNA made experts to think that the agreement had been reached well before military moves. In exchange for it, Russia would obtain the Qartabiyah air base near Sirte, as well as a naval base, again in Sirte, to give Russia the only thing it really wants to obtain from its Libyan adventure, i.e. a base in the Central Mediterranean region.

Recently, emerged signs of a Russian-Turkish coordination to work out a new map of influence sharing in Libya. The ministers of foreign affairs of both countries agreed on the need to create the right conditions for a peace process in Libya. The statement of the Russian Foreign Ministry, which quoted both ministers, Mevlut Cavusoglu and his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov, gave the impression that the two countries are following to a large extent the same pattern of their joint arrangements in northern Syria. Right from the beginning of the current developments in Libya, observers have been unanimous to say that the Russians and the Turks will be the ones deciding on any negotiations regarding arrangements in Libya.

The truce designed by Putin and Erdogan both in Idlib and, later, in Libya, conceals a strategic plan of considerable importance: the splitting up of Syria and then of Libya into regular and clear zones of influence, excluding the United States and its European and Western allies that will have no room in Syria nor even less in Libya.

Nevertheless, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu postponed unexpectatedly their visit to Turkey set to take place on Sunday due to last minute’s political differences between the two countries. Turkey’s Foreign Ministry stated that the meetings would take place “at a future date,” adding that Turkish and Russian presidents have “…agreed to continue working together to establish a lasting cease-fire in Libya.” Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, however, declined to comment when asked why the meeting between the two sides had been postponed. However, a Turkish official told Reuters on Monday that Ankara and Moscow postponed the talks over the GNA’s push to retake the strategic coastal city of Sirte and added that discussions were continuing behind closed doors.

Nevertheless, despite the differences over the capture of Sirti in Libya and the recent abrupt postponement of RussoTurkish talks on Sunday, the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov announced on Tuesday that

Ankara, Moscow and Tehran have agreed to hold a joint videoconference of the presidents of the three countries to be followed by a summit in Tehran. Mr. Lavrov added that Russia’s approach to the Syrian conflict could be applied to Libya, as its main aim was to prompt the conflicting parties to hold talks and provide the necessary conditions so that they could find common ground.

The French Wedge

A Libyan political source said that a Russian-French alliance is being formed in Libya, a move that seems to have disrupted Ankara’s plan for an agreement with Moscow that would enable it to take control of Sirte. The Russians and the French view Sirte with the same importance; both want the port and the base of Al-Qardabiya. Observers made a link between the postponement of the planned official visit to Turkey by Russian Ministers of Foreign Affairs and Defence, and a statement issued by the French presidency on Sunday, strongly criticising the Turkish intervention in Libya. The timing of both developments may indicate that there has been a last-minute coordination between Moscow and Paris.

Turkey’s ambitions will not stop its campaign to take over the coastal city of Sirte in central Libya, along with the industrial zone of oil terminals, but is also planning to lay hands on the Fezzan region in the south. The only problem is that southern Libya is the traditional zone of French influence and interests in Libya, which makes one wonder if Paris will move to defend its interests militarily or simply stop at issuing angry statements of condemnation. Despite the importance of the city of Sirte to Russia, Turkey was hoping to conclude a deal with Russia similar to the one that led to the withdrawal from West Tripoli, hence allowing Turkey to gain control of this coastal city. In Turkish calculations, Russia’s relinquishing Sirte does not seem impossible, since Ankara can offer Moscow the airbase of Al-Jufra, described as the most important base in Libya, while keeping the base of Al-Qardabiya to itself.

These calculations, however, seem to have not taken into consideration France’s interest in the city, particularly its port that Paris was planning to make its nearest gate to Africa.

Russia is aware that the recent French escalation, which was preceded by having French Rafale fighters fly over the city, would spoil any deal with Turkey that might take place. The Rafale overflights carried a message to Moscow, namely that if France had agreed to forcing the LNA to withdraw from the western region, it was because such a withdrawal was in line with the outcomes of the Berlin conference. France, however, is not willing to tolerate the surrender of Sirte and would not hesitate to move to counter any attack on the LNA forces in the city.

Italy: In search of realistic and coherent strategy

With its rather irrelevant Libyan policy, Italy has already been removed from the list of old and new powers that are currently redesigning the Mediterranean region. Italy does not even give a sign. Particularly against its oil and strategic interests. Yet the oil, migration, economic and even traditional interests should make any Italian government think that Italy, too, should take part -and possibly play a greater role- in the project for splitting up Libya.

There are expressed opinions that say it should pursue again the Italian national interests and stop using its Armed Forces as a sort of Red Cross or Civil Protection, as well as avoid believing, or pretending to believe blindly and optimistically in the “magnificent and progressive fortunes” of international Conferences. It should also think that Libya is not only the memory of a pre-Fascist colonial past, but the axis of its inevitable and huge interests in the Maghreb region and throughout Africa.

For Italy, Libya is obviously its oil. ENI has seven extraction-processing areas available but, according to 2019 data, Italy receives 7 million oil tons from Tripoli (and Sirte), equivalent to 12.1% of its total energy imports.

For Italy, Libya is only the starting point and often criminal regimentation of many migrants. Here the core of the issue is the real understanding of this phenomenon. The Libyan-Italian Memorandum of Understanding on Migration (LIMUM) was signed last February and later extended for additional three years. The LIMUM envisages the Italian support to the Libyan authorities, which can stop the boats and ships leaving from the Libyan coast and then make migrants return to their shelters on Libyan territory. In Abu Sitta, in fact, an Italian military ship is at anchor, which coordinates -with 70 soldiers- the work of the Libyan Coast Guard to fight against illegal migration.

Hence what can be done? To find an agreement between all EU countries, which are now very happy to palm off all the irregular migrants from Libya to Italy, so as to create -irrespective of the real presence of al-Sarraj’s GNA that would have many fewer problems to solve- a series of civil and organized control-selection-permanence camps to stop and identify part of the sub-Saharan migration, in the necessary time cycles.

No agreements are reached with the countries of the region. They are all too happy to get rid of a share of “human overproduction” and they will never accept to have to keep a “dangerous crowd” who, at the most, will only be used as blackmail for Westerners who, in the end, will receive it anyway.

Hence migration control camps out of the reach of al-Sarraj’s government and the major tribes operating as intermediaries of illegal migration. With a view to defending them, a NATO-based Control Force will be created, albeit with Rules of Engagement that do not seem to be drafted written -as has sometimes happened- by inexperienced people. It will be necessary, however, to choose a local champion that -together with the Italian Armed Forces, now getting out of their internationalist and pacifist dream or nightmare, will make Italian government pursue its real interests in Libya, regardless of its being one or many.

Obviously, with a view to protecting the Italian oil, Italy will need not only the intelligent work of ENI, which knows very well how to move on its own in those circumstances, but also a control unit involving both the Intelligence Services and Special Corps, as already provided for by Law No. 198 of December 11, 2015. A control unit that must “do politics”, i.e. choose, pay, direct and train a fairly significant group of local militants to oppose -also with weapons- the interests of other countries, possibly even allies, operating in that system.

All the Special Forces operate in crisis theatres permanently and with offensive and intrusive operations. Certainly also Italy has done so, albeit in areas where there was a wide network of protection and coverage by NATO and other allied countries. Now time has come to take action on its own.

CIA’s Special Activities Division has its own Special Operation Group (SGO), which operates in underground actions in major crisis theatres, with extensive legal rules and regulations.

The French Commandement des Operations Speciales (COS) operates permanently, and especially in Africa, together with the Brigade (or Service) Action of the Direction Generale de la Securite Exterieure (DGSE).

The SA is largely autonomous in the collection of all types of intelligence and choice of operations.

The British E Squadron operates with the Secret Intelligence Service and is made up of elements coming from the SAS and the SBS.

In short, whether Italy wants to protect realistically its interests, it will be necessary to pull claws out -with both secret and overt operations- to conquer the part of Libya needs to organize and pursue its interests.

Egypt’s message to Turkey: “We are keen on peace in Libya but ready for war”

Egypt, however, entered this Libyan game. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s announcement of the Cairo initiative to resolve the Libyan crisis, followed by “disbanding militias, handing over their arms, pulling out foreign forces, electing a ruling presidential council representing all Libyans and drafting of a constitutional declaration to regulate elections for later stages”, was soon followed by a massive deployment of troops on the Egyptian-Libyan border. Cairo realises that its initiative has confused the Ankara-Tripoli alliance. This alliance holds together only because of the continuation of war in Libya.

Cairo has not expected its initiative to be this easily welcomed by many parties. In fact, it had prepared for the scenario of its initiative being rejected by the GNA Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj and the GNA’s militias and allies. But the Egyptian proposal seems to have garnered the support of important international players, who urged all Libyans to take it seriously and warned them against jumping on the rash option of continuing the war.

Russian President Vladimir Putin had a phone conversation with his Egyptian counterpart Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. President Sisi presented Egypt’s consistent strategic stance towards the Libyan crisis, as embodied by the Cairo Declaration initiative and which was in accordance with the various international efforts as well. For his part, Putin praised the Egyptian initiative.

Earlier on, Egypt had announced an anti-Turkey alliance that includes Greece, Cyprus, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and France to confront Turkish moves in Libya and the Mediterranean. The announcement was made during a virtual meeting with the foreign ministers of these countries on May 11.

In a joint statement issued shortly after the meeting, the five-party alliance said it will focus on confronting the Turkish moves in the territorial waters in Cyprus, where Turkey has been carrying out “illegal” drillings in the Mediterranean under Cyprus sovereignty.

The alliance statement also criticized Turkish actions in Libya, calling on Turkey to stop the flow of foreign fighters from Syria to Libya and the MoU on the delineation of maritime borders in the Mediterranean and the understanding on security and military cooperation, both signed in November 2019 between Turkey and the internationally recognized Tripoli-based Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) headed by Fayez al-Sarraj.

Cairo believes that the opportunism of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will make him persist in his reckless endeavour by continuing to favour and support the military option. Ankara is aware that the major world powers will not look favourably at its breach of the rules of world geopolitics. So if its intervention in Libya was tacitly blessed by some Western powers, in order to achieve specific goals, its going all out militarily and bringing in mercenaries did not sit well with other major powers, especially France and Italy.

President Al-Sisi’s initiative is obviously designed to regain control of the situation in Libya, after Khalifa Haftar’s evident defeat, in open conflict and competition with Turkey and possibly against the aims of Qatar and probably of France itself, whose Intelligence Services’ Brigade Action greatly supported Haftar’s LNA and continues to do so.

The idea underlying Al Sisi’ strategy, but also Russia’s, is that Libya should be pacified and rebuilt following the current political-military fault lines, without waiting for an impossible future reunification.

Moreover, the very recent Egyptian plan suggests -in agreement with al-Sarraj himself- the removal of all foreign mercenaries present in all factions and then the creation of a “Presidential Council” elected by all the Libyan people equally representing the three historical regions, namely Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan, under the U.N. control, and also including women, young people and old tribal leaders.

A vague, complex, cumbersome and currently impracticable project which, however, shows that Egypt wants to wait for better times to do what it has always wanted to do: to gain influence over the part of Libya bordering on Egypt and differently regulate both the migration of Egyptian workers to the Libyan oil wells, and the oil issue itself, both with al-Sarraj and with those who will reconquer Cyrenaica, if Haftar failed again.

Sisi’s Cairo Declaration was welcomed by the Arab Gulf states and Russia, while the GNA backed by Turkey remains disinterested and hopes to make some more territorial gains so as to be able to negotiate from a position of strength. By contrast, the LNA commander, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, immediately announced his adherence to the cease-fire. Haftar and his backers have suffered a series of battlefield setbacks in western Libya.

Towards another peace truce…

The GNA and Turkey estimate -rightly so- that any respite at this point will be utilised by Haftar and his backers to recoup and plan anew to return to the battlefield to make another bid to rule Libya. They eye Cairo’s declaration to be more about seeking to salvage what remains of Haftar’s project. As Egypt, the UAE, France and Russia have invested billions of dollars in this project, they are attempting to create some sort of momentum to slow down the significant military losses on the ground as UN-backed forces project power over Sirte and the oil fields in the east.

As a result, the establishment of lasting peace and stability in a failed state-status geography such as Libya, can be made possible by the presence of an authority capable of ensuring the security of its borders, institutions and citizens. In the current situation, it is difficult to say that there is an international and local conjuncture that would allow such an authority to be established. Under these circumstances, deploying diplomatic channels and sitting at the table can only produce a brief period of stability, such as a ceasefire. On the other hand, there can be no solution to protecting local actors, who see the competition as a zero-sum game from the structural pressures caused by anarchy in the country. Rather than laying the groundwork for lasting stability, short-term ceasefires allow the losing side to recover and attack again. It should be read in this context that general Haftar, who has previously heeded the calls for a ceasefire, has raised the issue of a ceasefire in the recent months. Furthermore, unless the structural problems are addressed, these initiatives will be a continuation of the artificial peace and stability environment created by the elections in 2012 and 2014 and by the political agreement in 2015.

Looking at the current situation in the international arena, it is not possible to establish such cooperation. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), France and Egypt, for instance, have openly expressed their support for the peaceful resolution of the crisis, but are deeply disturbed by the engagement of Turkey in Libya and are in favor of continuing the fight against “radical” elements, referring to the GNA’s troops. In parallel with this rhetoric, they continue to contribute to the military capacity of Haftar. Russia, on the other hand, has a similar attitude. Moscow, which has held talks with representatives of the GNA on the one hand and declared that it favors the creation of a permanent ceasefire, and the deployment of planes to the airbase in Cufra on the other hand, demonstrates its belief in the resolution of the crisis by military means. It will not be enough for one of these stakeholders to radically change its current position.

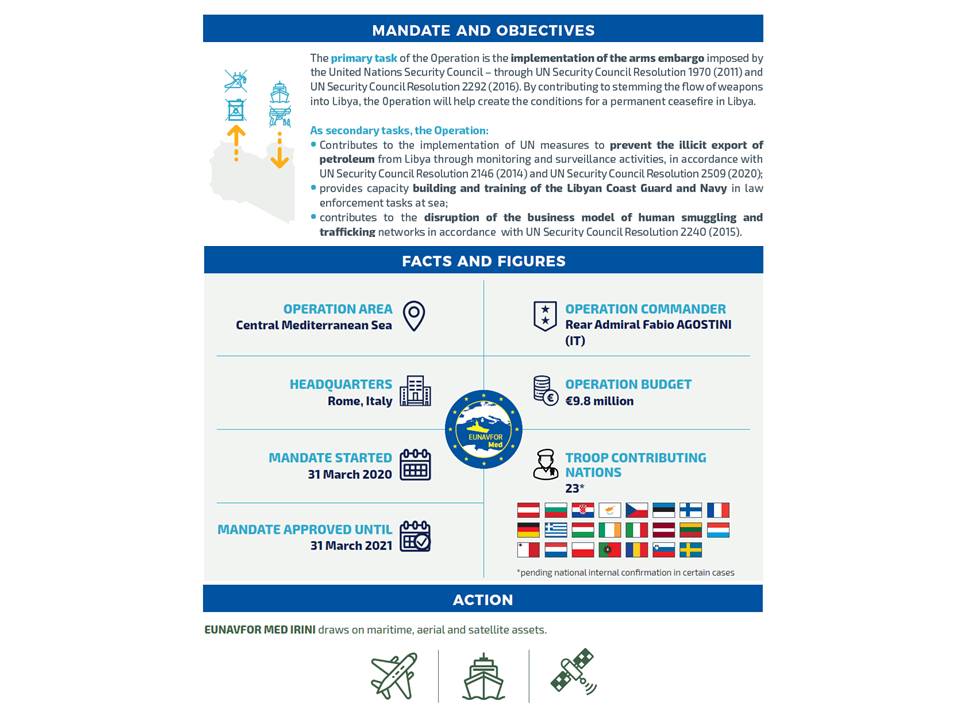

EU launches Operation EUNAVFOR MED “IRINI”

The Berlin Libyan Conference ended leaving the impression of a public policy exercise set by Germany in an effort to reclaim its leading role in Europe. As much as Germany tried to imitate the historic “Berlin Conference” of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference, or West Africa Conference that regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany’s sudden emergence as an imperial power.

However, the modern Berlin Conference did not yield a result which would justify its purpose, as no cease fire was agreed. The Conference was successful in the sense that the organizers managed to get both belligerent parties, not to speak directly to each other but to speak separately with all other actors, which is quite something. The Conference concluded with a document, a kind of roadmap showing how to achieve a durable cease fire, and this is also positive.

The Berlin Conference unanimously agreed, as Chancellor Angela Merkel said, to respect the arms embargo set by the UN and to control it more effectively than it has been in the past. Such a decision clearly implies that the Conference decided to keep equal distances from the belligerent parties, despite previous open support to Libya’s UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) under Prime Minister Fayez Sarraj.

The European Union is trying to remain in the picture of the Libyan crisis as a primary actor. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and EU High Representative Josep Borrell committed to play an important role in the Libyan civil war and to contribute “…to the monitoring of the ceasefire and the respect of the arms embargo.” As a result, the Council reached a political agreement to launch a new operation in the Mediterranean, aimed at implementing the UN arms embargo on Libya by using aerial, satellite and maritime assets on 17 February 2020.

“IRINI “a Greek word for “peace”, which succeded the previous EUNAVFOR MED “SOPHIA” launched on 22 June 2015, as part of the EU’s comprehensive approach to migration, and ceased permanently on 31 March, has as its core task the implementation of the UN arms embargo through the use of aerial, satellite and maritime assets. In particular the mission was organised to carry out inspections of vessels on the high seas off the coast of Libya suspected to be carrying arms or related material to and from Libya in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 2292 (2016).

As secondary tasks, EUNAVFOR MED IRINI also:

– monitor and gather information on illicit exports from Libya of petroleum, crude oil and refined petroleum products

– contribute to the capacity building and training of the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy in law enforcement tasks at sea

– contribute to the disruption of the business model of human smuggling and trafficking networks through information gathering and patrolling by planes

The Force Command will be assigned to Italy and Greece every six months alternatively. The rotation of the Force Commander will take place together with the rotation of the flagship. Currently, IRINI is led by Rear Admiral Fabio Agostini as EU Operation Commander, and its headquarters are located in Rome, Italy.

On 4 May, the European Union Operation EUNAVFOR MED IRINI commenced its activities at sea. The Operation was organized to use 4 vessels contributed by France (firgates Jean Bart and Aconit), Greece (frigate Spetsai) and Italy, one Maltese boarding team and three directly assigned patrol aircrafts from Germany, Luxembourg and Poland.

The European Satellite Centre (SatCen) provides satellite imagery support. It is a decentralised agency of the European Union working under the supervision of the Political and Security Committee and the operational direction of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

The staff employed come from the following countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Estonia, France, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Czech Republic, Romania, Slovenia and Sweden.

Other special assets necessary to carry out the operation’s tasks, such as submarines, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and Airborne Early Warning aircraft, are also expected to support the operation, offered by Member States on an occasional basis.

Particular attention is paid to COVID-19 countermeasures. The Operation Commander has issued guidelines to the participating countries to reduce the risk of contagion in the Headquarters and on board ships and aircrafts. The latter have to be declared “COVID-19 free” by the flag State before they can be included in the Operation.

Good intentions are not enough…

It was, perhaps, prophetic that EUNAVFOR MED “IRINI” was launched on April 1 “Fools Day”. Right from its start, came under fire by Libyan officials of the Government of National Accord as it didn’t include monitoring the eastern region’s borders, from which arms are being provided to Haftar’s forces.

The Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar also, accused the EU that the Operation IRINI holds no legal grounds, as it is run without any official request from the legitimate GNA. He explained that the control on access by sea cannot be considered an arms embargo, rather a block on legitimate government activities, whilst lending support to Haftar’s forces and indicated that some European countries are not willing to be part of “IRINI”, calling the operation’s member states to review their stances in supporting warlord Haftar against the GNA.

The recent incident of the Hellenic Navy’s vessel, which was monitoring the movements of the Tanzanian-flagged Turkish ship suspected of carrying military equipment, sailing southwest of Crete in the direction of northwest of Benghazi, accompanied by three Turkish frigates, strongly indicates the ineficiensy of the Force to complete its mission, owed mainly to the indifference and/or weakness of European Union to impose its intentions in the area.

The incident raises a number of issues such as whether Operation Irini can in practice monitor the embargo. Turkey appeared to have a total of eight ships in the area the day of the incident, while the Operation Irini’s deployed units was just the Greek frigate.

It was not the first time this happened. On June 10 “Cirkin”, the Turkish vessel suspected of smuggling weapons to Libya, had “switched off its tracking system, masked its ID number and refused to say where it was going” the French Armed Force Minister Florence Parly said, while accusing the Turkish navy escorts of using NATO call signals to cover for the Tanzanian-flagged cargo ship and flashed their radar lights three times at the French warship “Courbet”, on a NATO mission to check whether the Turkish cargo ship was smuggling arms to Libya.

A senior Turkish military official said on Wednesday it was “completely untrue” that the Turkish navy had harassed a French warship, denying the accusations. The Turkish military official told Reuters the French warship did not establish communications with the Turkish ship during the incident.

In fact, Operation Irini has not received any substantial support so far from the European Union member-states. France, for instance, has stated that Turkey is pursuing “…an even more aggressive and insistent stance, with seven Turkish ships deployed off the Libyan coast and violations of the arms embargo.”

Relations between Turkey and France are already strained on a number of issues ranging from Syria to oil exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean. President Macron wants talks with NATO allies to discuss Turkey’s increasingly “aggressive” and “unacceptable” role in Libya. The French foreign ministry has accused Turkey’s navy of “…acting in a hostile manner towards its NATO allies” to prevent them from enforcing a United Nations arms embargo on Libya.

However, despite criticism of Ankara’s efforts of thwarting peace truce by breaking the UN arms embargo, France has not sent any frigate so far but has stated that its frigates could intervene within 72 hours!

Italy, which is leading EUNAVFOR MED Irini, conduct joint maritime drills with Turkish submarines in the Mediterranean Sea. Turkish-Italian relations appear to have strengthened after Turkey’s intelligence service played a role in the rescue of a kidnapped Italian aid worker in Somalia.

Italy has also refused to condemn Turkey’s territorial claims in the Eastern Mediterranean, which has erupted into an ongoing dispute between Ankara and a group of countries in the region looking to capitalise on offshore gas and oil, despite the fact that initially participated to EastMed pipeline project.

Germany has unenthusiastically agreed to provide a marine surveillance plane as support of the operation.

Malta also, has formally given notice to the European Commission that it will no longer commit any military assets to the EU’s Operation IRINI, it will no longer provide its boarding team, and it will veto decisions on Operation IRINI that concern spending procedures for disembarkation of migrants, port diversions, and the eligibility of drones.

“IRINI” is effectively operating with just one vessel, the Hellenic Navy’s frigate “Spetsai” tasked to monitor a huge area between Crete and Libya.

Even EU’s High Representative Josep Borrell, expressing concern over the escalation of tension in the Eastern Mediterranean, hinted last month that “IRINI” was a failure as it didn’t have the needed capabilities to kick off work, confirming that the Operation is facing challenges in terms of equipment and finance, adding that the current capabilities are barely sufficient to start off the operation and cover the first months of the process. Recently called for the strengthening of Operation Irini in a videoconference of EU defense ministers: “Operation Irini has hailed ships, since it was launched, on more than 130 occasions. More than 100 in relation with the arms embargo, 29 in relation with the oil embargo, which are fueling the Libyan conflict. For sure, it can do more and better.”

Mr. Borrell also said that together with NATO “…are discussing how to establish a new arrangement of cooperation -not participation- between Operation Irini and NATO, once again in our shared interest. I hope that this cooperation agreement can be set up on the next days.”

Two NATO diplomats, however, raised doubts about whether Turkey would let such an arrangement happen, and because the 30-nation military alliance operates on the basis of unanimity, NATO’s support cannot be guaranteed.

Asked what the response might be, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg answered “we are looking into possible support, possible cooperation, but no decision has been taken. There is dialogue, contacts, addressing that as we speak.” He noted that NATO did provide support to the EU’s previous naval operation “SOPHIA”, which had a different mandate to “IRINI”.

EUNAVFOR MED “IRINI” UNITS

HS “SPETSAI” (F-453)

HS SPETSAI (F-453) is a MEKO200HN class Frigate, the second vessel of her class in service of the Hellenic Navy. She was built in Skaramagkas Hellenic Shipyards and commissioned in 1996. The vessel’s name is derived from the island of Spetses, which contributed to the National Independence War of 1821 with its formidable flotilla.

HS SPETSAI is a multiple purpose Frigate. She can operate in a multi-threat environment and is capable of fulfilling all required tasks in the framework of EUNAVFOR MED Operation Irini. The ship has taken part in numerous multi-national and NATO operations, exercises and training activities.

The ship can accommodate a single Sikorsky S-70B Aegean Hawk helicopter.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Length: 117 m

Beam: 14.8 m

Draft: 6 m

Displacement: 3.350 tns

Speed: 32 kts

Propulsive Power: CODOG (2 Gas Turbine LM2500 & 2 Diesel MTU20V)

P-3C ORION

The Bundeswehr (German Federal Defence Forces) has eight aircraft of this type. They are based at Naval Aviation Squadron 3 “Graf Zeppelin” in Nordholz, Lower Saxony. P-3 ORION borns as fighter plane is designed for submarine hunting. Mostly, it is used for long-range reconnaissance and monitor sea areas closely from the air.

Radar, laser range finder and the infrared video-camera combination of type MX-20HD make the large reconnaissance aircraft the “flying eye” of the navy.

The crew consists of at least eleven soldiers. These are pilot and co-pilot, a tactical coordinator and a navigation officer who takes over the radio traffic at the same time. System technicians, on-board mechanics as well as three above and two underwater operators complete the crew.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Lenght: 35,6 m

Wingspan: 30,4 m

Height: 10,1 m

Empty weight: 34650 kg

Max take-off weight: 64,4 t

Speed: 750km/hr

Endurance: 14 hrs

Drive: 4 turboprop engine

POLISH An-28B1R BRYZA

Missions performed:

– Search and Rescue activities

– Air reconnaissance missions

– Identification of ships, tracking and cooperating with Polish Navy vessels

– Ecological monitoring of Polish EEZ (Economic Exclusive Zone)

– Executing recce and photographic intell missions

– Transport missions

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Lenght: 13,10 m

Wingspan: 22,06 m

Height: 4,9 m

Max take-off weight: 7.000 kg

Speed: 350 km/hr

Endurance: 3,5 hrs

LUXEMBURG Swearingen-Fairchild Aircraft

The aircraft is fitted with a suite of equipment to allow it perform

maritime surveillance. Furthermore, the Merlin has been employed in the previous EUNAVFOR MED Operation SOPHIA from 2015 to 2020

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Lenght : 12,85 m

Wingspan: 14,10 m

Height : 5,13 m

Max take-off weight : 6.000 kg

Speed : 556 km/hr or 300 knots

Endurance: 6,30 hrs