The Greece-Egypt Agreement took by surprise and infuriated Ankara, forcing it to react by raising tensions, endangering the coherence of the Alliance and the regional stability…

The Turkish-Greek crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean has entered a new tense phase after the signing of a maritime treaty between Egypt and Greece on Thursday, that partialy delimited the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) between the two countries in an area containing offshore oil and gas reserves.

While both NATO allies, Greece and Turkey have been at odds for years over sea, air and land rights, tensions have flared in recent months, with Greece warning it would wage war if Turkey moved to act on its energy designs, drilling or even exploring in waters in Greece claims.

Refusing to stop its belligerent behaviour, Ankara had announced its intention to conduct seismic explorations in Egypt’s EEZ too, triggering a strongly-worded response by the latter. Last week, Turkey announced it will search for gas in the Eastern Mediterranean in areas it claims are within its continental shelf, which bothered Egypt and Greece. Ankara’s most recent steps was a major factor that accelerated the signing of the maritime Agreement between the two countries.

Turkey’s intentions are a real threat for the integridy of NATO’s Southern Flank, remininscing the old 1974 day’s of its ATTILA invasion in Cyprus and the dissarray it caused back then to the Alliance.

Anastassios Tsiplacos - Managing Editor

On July 22, we wrotte “There are fears (in Athens) that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan might try an intervention in the Eastern Mediterranean in a bid to prevent an agreement on the delineation of an EEZ between Greece and Egypt, which is currently being discussed between officials of the two countries.” (see: Drums of war are beating more loudly in Eastern Aegean)

Greece, indeed, continued its diplomatic counteattack, after the recent deliniation aggreement with Italy. In a surprise move, Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias secretly jetted off to Egypt to seal the deal, finalizing a strategic alliance with Cairo, which diplomats in Athens said required 13 rounds of negotiations and 15 years to ultimately conclude, due to Cairo’s reluctanty to interfere in the Creco-Turkish disputes.

The deal is a response to the agreement signed in November between Turkey and Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) which sought to establish an EEZ to legitimise Turkey’s claims to offshore gas and oil reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean, much to the ire of Greece, Egypt and other nations collaborating on the EastMed pipeline project of their own. The Turkish-GNA agreement created a sea corridor between the two nations which cuts through the boundaries claimed by Greece and Egypt. Cairo and Athens have condemned Turkey’s deal as a violation of international law.

Egypt, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Greece and Cyprus last month jointly sent a letter to the Secretary General of the United Nations asking that the U.N. not register the Turkey-Libya maritime border deal in its list of international treaties.

Experts have raised doubts about the legal competence of President Sarraj to enter into such a deal, having only a temporary if not an expired mandate to head Libya’s presidential council. Media reports said Sarraj himself shared in some of those reservations before signing the deal under “Turkish pressure”. The five countries said last year’s deal gravely jeopardises regional stability and security. They contend the agreement disregards the rights of other Eastern Mediterranean states and contravenes international law by not recognising island rights in maritime zones.

The Greece-Egypt Agreement

Greece, which has not officially claimed an Exclusive Economic Zone, has however signed a total of two partial agreements with Egypt and Italy. The agreement with Egypt effectively plugs a number of gaps that Ankara sought to invest in to strengthen its relations with Presidetn Fayez al-Sarraj, head of the Government of National Accord (GNA) in Libya.

The agreement basically scatters away many of the cards that Turkey sought to forcibly seize in the Eastern Mediterranean, believing that reaching an understanding between Cairo and Athens would be difficult and will take a long time, during which it could entrench its ships in some gray areas of the economic zones of both countries. Ankara has indeed jumped on these areas and tried to exploit them for political and economic gains.

The agreement is based on UNCLOS, recognising the right of islands, as it should. Greece made some serious concessions to Egypt to get the deal signed, including limiting the scope of the maritime zones, in order to strengthen its diplomatic hand. But it needs to evolve further to cover the eastern part of the two EEZs, delineation of which is affected by Cyprus and Kastellorizo eventually. It is an excellent start, given the circumstances, reinforcing internationally accepted maritime principles.

Will Greece and Egypt rush into drillings? Both countries will need to complete EEZ delineation first -including Cyprus- and then divide their respective EEZs into exploration blocks. That would eventually enable the two countries to proceed with licensing rounds. Its only then that exploration and drilling can start.

Turkey taken aback…

The partial deal between Egypt and Greece had a really bomb-like effect in Ankara and elsewhere in Turkey and has made the architects of Turkey’s so-called “Blue Homeland” naval expansion doctrine angry, to say the least. “What are Greece and Egypt doing there?” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wondered, describing the agreement as “nonexistent.”

In the wake of Thursday’s agreement between Greece and Egypt, he denounced it as invalid and announced drilling operations in areas outlined in the Turkey-Libya accord which Greece said was nullified by its deal with Egypt. He also called off exploratory talks with Greece whose commencement on August 28 had been expected.

Conspiracy Scenarios

The amount of surprise was such that certain political circles in Turkey -some of them close to the inner circle of the Turkish President- circulate various scenarios wondering how Egypt agreed to the deal, despite the loss of maritime zones Turkey offered, and what concessions Greece made in return, and how and by whom both countries’ “losses” will be compensated. They believe that Russia, France, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) “strongly encouraged” this deal. According to some commentators, Germany has contributed to this as well. The country’s recent deployment of the frigate “Hamburg” to EUNAVFOR MED “IRINI”, and its concerns to protect its giant investments in Libya, which were not mentioned much until today, are clues of this. In the bigger picture of the conflict between NATO and the EU, which they analyze it as an EU-U.S./NATO conflict, while Egypt and Greece are making this deal with Russia, France and the UAE’s support, it means they are advancing towards the U.K.-NATO-U.S. position with Turkey on their target.

Turkey has accused Greece of trying to exclude it from the benefits of oil and gas finds in the Aegean Sea and Εastern Mediterranean, arguing that sea boundaries for commercial exploration should be divided between the Greek and Turkish mainlands and not include the Greek islands on an equal basis.

Last month, Greece and Turkey reached the brink of an armed confrontation after Ankara’s decision to send a research vessel escorted by warships to Kastellorizo to conduct oil and gas exploration. Turkey said it had agreed to temporarily suspend gas and oil exploration off the Greek island of Kastellorizo, depending on the outcome of negotiations with Greece and Germany, which has taken a mediating role in the spat, to reduce tensions with Greece and the European Union.

“Merkel asked me to stop drilling,” President Erdogan said, adding that he told her, “If you trust Greece, the others, we will take a break for a few weeks, but we do not trust them.” Erdogan concluded by saying that “[the Greeks] did not keep their promises”, while at the same time the “Barbaros” vessel continued exploring in Cyprus’ EEZ.

President Erdoğan, however, seems to have been aching all-along to end the pause, as continued exploration and drilling in the Εastern Mediterranean is part of his regional strategy of expanding de facto control by Turkey of the region’s maritime resources. He quickly used the announcement of the deal between Greece and Egypt to expedite the drilling activities.

EU-US anxious efforts…

“The United States encourages all states to resolve their maritime boundaries peacefully in accordance with the international law,” State Department’s spokesperson said after the signing of the maritime borders agreement between Greece and Egypt on Thursday. At the same time,

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo raised the crisis in a call with Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry of Egypt, discussing the “importance of supporting a U.N.-brokered cease-fire in Libya through political and economic talks,” according to the State Department, while sources said that they talked about the maritime agreement with Greece and its possible future implications.

With tensions running high between the two nations, EU member states and the U.S. State Department have urged Turkey to back off from its ambitious energy designs, at least for now. They are also pushing Greece and Turkey to return to the negotiating table in hope of trying to sort out age-old differences. It has been four years since the two countries have held regular diplomatic meetings.

Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias said, “While there was an initial understanding between us to start exploratory contacts, Turkey withdrew from this understanding.” He expressed the hope that “this is a temporary decision under the state of inexplicable anger, and I say inexplicable, because Greece took an absolutely legal action.” He reiterated that Greece is willing to defend its positions in any court, such as the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

Regional co-operation through Trilaterals

In a world of pandemics, forever wars, and great power showdowns, it might come as a surprise that region’s next crisis is emerging from disputes over maritime law. In the Eastern Mediterranean, a possible confrontation is under way between countries in the region for access to recently discovered gas fields. Conflicting legal claims to the fields are merging with old and new conflicts, and have led to the creation of a new geopolitical front in the Eastern Mediterranean that should cause stakeholders substantial concern.

Given the significant breadth of Turkish claims and its extremely maximalist positions on issues directly related to Greece and Cyprus, they deemed necessary to formulate a comprehensive policy and to utilize the entire foreign policy toolkit: alliances, bilateral diplomatic contacts and the opening of parallel communication channels, exploring prospects for bilateral and/or trilateral economic and other cooperation, as well as sending a clear message about regional stakeholder’s red lines, while maintaining a strong capacity of deterrence.

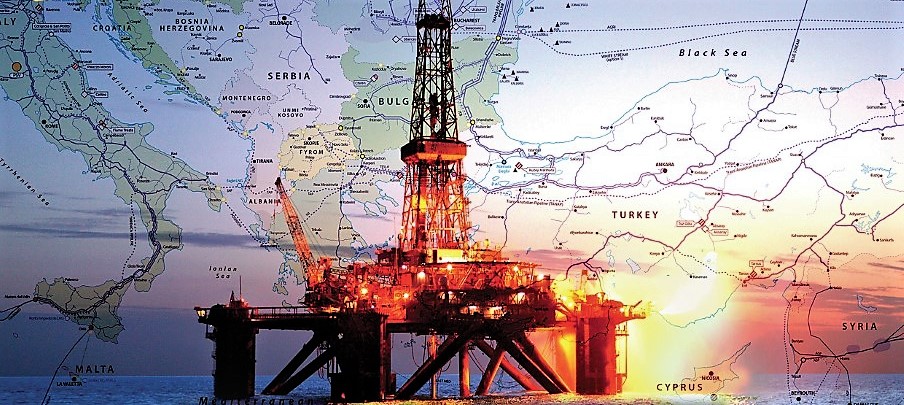

Israeli, Cypriot and Greek energy ministers created joint task forces to evaluate the feasibility of several options. For exportation, they are considering the EastMed Gas Pipeline to carry gas from Israel and Cyprus to European markets through Greece, and a Cypriot LNG plant near Vassilikos on the southern coast of the island. However, other projects are simultaneously being evaluated by each government according to its own energy-security agenda and national interests.

The recent agreement between Greece and Egypt was nurtured from the second major regional Trilateral between Egypt, Greece and Cyprus. Unlike previous trilateral summits, which focused on all the issues of cooperation between the three countries. The 7th Trilateral Summit on October 8th 2019 in Cairo, aimed at forming a strong energy-based alliance in the East Mediterranean. The joint declaration stated that the three countries underlined the importance of making additional efforts to boost security and stability in the region, and strongly called on Turkey to “end its provocative actions” in the Eastern Mediterranean condemning them as “unlawful and unacceptable”.

Common Aeronautical Exercises

To enhance their co-operation and send the message that the Trilateral “means business” Egypt, Greece and Cyprus have been intensively involved, during the last 6 years, mainly in bilateral exercises, in order to enhance the security character of their cooperation. Within the framework of this practice, the large-scale, “MEDOUSA” exercises, for air and naval forces of Greece and Egypt, take place in the wider region of Alexandria, Crete and the Eastern Mediterranean. For the first time on Egypt’s part the MISTRAL helicopter carriet participated in Greek waters, and actually Greek Chinook (CH-47D) and Apache attack helicopters both landed and operated from it.

The exercise scenarios are gradually being expanded and the participating forces are also increasing both in size and in the variety of the hardware involved.

The breakdown of the participating forces indicate the scale of the exercises. Greece usually participates with 2 frigates and their on-board helicopters, 1 submarine, 8 F-16s, 1 C-130, 1 AWACS aircraft, 1 CHINOOK helicopter, 2 AH-64 attack helicopters and Special Forces personnel. Egyptian forces participate with a MISTRAL class helicopter carrier, 2 frigates, 1 submarine, 2 missile boats, 6 F-16s, 2 RAFALEs, 1 E2-C AWACS aircraft, 1 helicopter and Special Forces personnel. Cyprus participates with an offshore patrol vessel, and Special Forces personnel.

NATO’s Southern Flank in danger of dissolvement…

Turkey’s intentions are a real threat for the integridy of NATO’s Southern Flank, remininscing the old 1974 day’s of its ATTILA invasion in Cyprus and the dissarray it caused back then to the Alliance. A confrontation between the two NATO members, Greece and Turkey, continues to trouble the Alliance’s Southern Flank after 46 years. Tensions flared up last month, prompting German Chancellor Angela Merkel to hold talks with the country’s leaders to ease tensions.

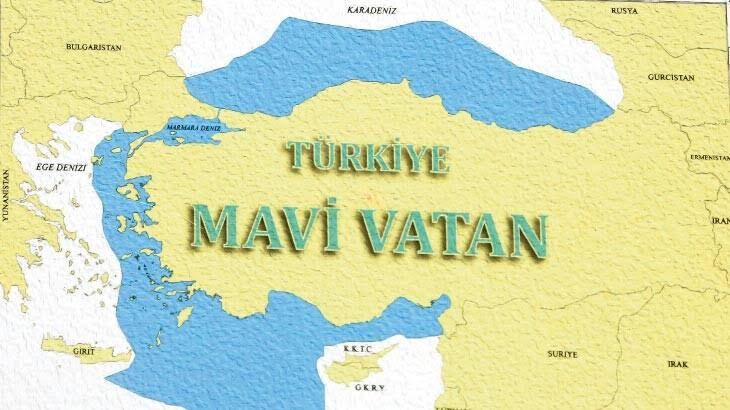

The main destabilizing factor for NATO’s Southern Flank is Turkey’s revision policy in the Middle East and North Africa. The ultra-nationalist “Blue Homeland” military strategy is clear in its goals. President Erdogan’s military doctrine targets the domination of the Aegean, most of the Mediterranean, and of the Black Sea.

Increasingly assertive, ambitious and authoritarian, Turkey has become the “elephant in the room” for NATO. A more aggressive, nationalist and religious Turkey is increasingly at odds with its Western allies over Libya, Syria, Iraq, Russia and the energy resources of the Eastern Mediterranean. However, Alliance’s officials also suggest that Turkey is “too big, powerful and strategically important…to allow an open confrontation.”

Turkey indeed, has moved from being the secular, enlightened NATO member to being the Islamic Republic of Turkey. It is transforming to the Sunni equiIvalent of Iran, with identical expansionist ambitions. The expansionist Turkish policies in Libya are an implementation of the global blueprint of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, namely, to establish a pan-national Islamist caliphate. Erdogan is using the traditional relations the secular Turkish state had with the West, especially with NATO, to legitimize his expansionist moves in the Middle East, North Africa and parts of Europe. While Ruhollah Khomeini’s revolutionaries stormed the American Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979, mr. Erdogan very patiently waited, making his interests seem almost aligned with those of NATO.

The outlook is rather grim. At the start of Libya’s war, no one expected the conflict to intersect with Eastern Mediterranean energy competition in such a significant way. Ankara’s strong support for the Libyan Tripoli-based government has not only tilted the power structure in Libya; its military moves, aiming to not only open up Africa’s largest oil reserves to Turkish companies but also to expand its sphere of influence in the Eastern Mediterranean, are a direct threat to Greece and Cyprus. A military incident between Greece and Turkey could occur in the Aegean, with the US absorbed in its domestic issues and Germany trying to intervene; and a clash between Ankara and Cairo in Libya is entirely possible.

The Eastern Mediterranean tinder box is not only a threat to its offshore gas future. A military conflict in the region, involving Turkey, will threaten several major commodity and trade chokepoints. A confrontation could lead to a major blockade of the Dardanelles (Istanbul), the Suez Canal (Egypt), and the route between Libya and the southern Italian islands. Ankara’s regional power play is not only of concern to the littoral states of the region, but also to GCC oil and gas exporters and EU-Asian trade.

NATO’s image is tarnished. During a period when the Alliance is taking steps to bolster its presence in the so-called “South,” its contradictory role in Libya in 2011, along with Greek-Turkish tensions and Turkish-French spats, cannot be sidelined. The positions of the NATO member countries differ in their assessment of Turkey’s actions. In 2020, a military confrontation between NATO members (Turkey-Greece-France) or allies of NATO (UAE, Egypt, Israel) in the Middle East is no longer unthinkable. Ankara’s approach in Libya suggests an aggressive Turkish military strategy intended to set up military bases in the region. Not long ago, for example, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs criticized France for failing to be impartial. French President Emmanuel Macron then posted a Facebook message in Greek exposing Turkish tactics in the Eastern Mediterranean. Mr. Erdogan’s regional gamble could end up being a major catastrophe.

What Greece expects from the Alliance…

Greece expects NATO to play its role with regard to Turkish activities in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean, Prime Minister Mitsotakis has indicated, saying that the alliance’s “hands-off approach” is no longer acceptable.

“I think within NATO it is very clear that this hands-off approach –that “oh we have two NATO partners so we’re not going to go into the details”– is no longer going to be accepted. I raised this with Secretary-General [Jens] Stoltenberg that we’re a NATO contributor and an ally and … when we feel that a NATO ally is behaving in a way that endangers our interests, we cannot expect from NATO a similar approach of “we don’t want to interfere in your internal differences.” This is profoundly unfair for Greece,” the Greek Prime Minister said during the online “Aspen Security Forum” on Wednesday.

“I think the alliance will find itself faced with the reality that an important member… behaves in a way that undermines the alliance and the interests of other members of the alliance. It’s an issue we can no longer afford to put under the rug,” he said, adding that Turkey’s “unreliable behavior” within the alliance, also raises security concerns. “Purchasing the S-400 system is an issue of concern to all of us, including the US because it compromises the F-35, which is an integral part of NATO,” he added.

The United States should be alarmed by Ankara’s activities in the Eastern Mediterranean but also its involvement in Libya, Mitsotakis said, adding that a visit to Washington last December gave him a sense that “there is a bipartisan understanding that the relationship with Turkey is not the same that is was three, four years ago. It’s not as predictable. Pieces of legislation sponsored by Senator [Robert] Menendez clearly are an indication that there is a much better understanding in Washington of what is really happening in the Eastern Mediterranean,” the Greek premier said in reference to the Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act of 2019.

NATO’s Secretary Jens Stoltenberg has repeatedly declared support for Turkish activities in Eastern Mediterranean as allegedly stopping Russian expansion in this region. Unfortunately, this approach only deepens the division in NATO and causes countries such as France or Greece to try to get along with Russia as the only entity that can influence Turkey. For the Kremlin, however, this is an ideal situation, a dissonance in NATO is in itself desirable, especially since it cannot be ruled out that it will end in war. However, entering the role of a mediator gives Moscow full opportunity to safeguard her own interests.

THE KEY PLAYERS OF THE CRISIS

Nine countries (Israel, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Russia, Italy, France and USA), five of them the oldest NATO members, have major to very high stakes in the “Big Energy Game” of Eastern Mediterranean’s region. The experience of recent years suggests that ensuring peace and stability in the region is first and foremost the responsibility of these regional powers. The key players, however, of the current crisis are Turkey, Egypt and Greece, the last being connected directly with the Republic of Cyprus.

(see: REPORT #4 S.E. Europe – S.E. Mediterannean. Multiple Energy Challenges and Complex Geopolitics)

TURKEY: Like a lorry in downslide without brakes…

“Political Vision 2023”, portrays Turkey as a rising global player, a powerful mediator for peace and stability in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean. The Vision’s statement specifically notes the place of energy in foreign policy, and highlights Turkey’s approach to energy trade as a “common denominator for regional peace.” It is clear that Turkish government openly associates the country’s political and economic stability with its regional energy-related interests. In addition, Turkey has set the ambitious target of becoming an energy hub, not only to generate additional revenue, but also to acquire more geopolitical influence in the region. Turkey is trying to assert itself across the swath of Iraq, Syria and all the way to Libya, with its eyes set on having power not seen since the Ottoman Empire more than 100 years ago. (see: The Ottoman Empire Strikes Back?).

Shortly before passing laws that allow Turkey to send troops and proxies to Libya, and before sending the first group of troops to back the Tripoli government, Turkey’s state-run Anadolu Agency published a document, written by foreign policy analyst Mehmet A. Kanc, that amounts to the announcement of an official new geopolitical strategy justification for its interference in the Eastern Mediterranean and Libya. Turkey’s plans for the region, as defined in the Andolu document run as follows:

“Turkey’s new defense territory covers on the one end the west and south of the Greek island of Crete and the headquarters of the Turkey-Qatar Combined Joint Force Command overlooking the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf and the Somali Turkish Task Force Command in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, on the Indian Ocean coast on the other….Turkey now wants to strengthen its defense line with a new link in Libya.”

For anyone looking to interpret Turkey’s moves in that region, this commentariat should be the beacon. Aside from asserting political, military, and economic interests on the basis of Ottoman-era borders, and laying claim to vast maritime territory from Cyprus to Somalia, Ankara is asserting an ideological supremacy that reflects steps it has been taking elsewhere.

Turkey’s claims to the Eastern Mediterranean and to Libya in the manifesto of its naval and geopolitical strategy follow from this “ideological defense line” against the Saudi presence and influence in the Levant and in Africa, where Ankara seeks to displace Riyadh-led Islam with its own religious and humanitarian leadership.

Turkey’s moves is a gradual effort to entrench its demands in the Eastern Mediterranean and to test the resolve of parties with interests in the region, such as the United States, Russia, Israel, Egypt, Greece, France and Italy. In its effort to find alternative energy sources for its internal consumption, as well as for the realization of its strategic aims to become a significant peripheral stakeholder, Turkey strives to subverse the current status in the region with high risk actions and statements.

More than anything, Turkey’s entry into the Libyan conflict and posturing off the coast of Cyprus are an indication of the lengths to which Ankara is willing to go to prevent the emergence of a new order in the Mediterranean. Turkish escalation is designed to make it unprofitable -politically, diplomatically, and commercially- to attempt to ignore or exclude Turkey’s interests. While Turkish exploration ships close to Cyprus have made no significant discoveries, they have made Ankara’s intentions abundantly clear.

If anything, those who observe Turkey today should take it into account, with the perspective of what the duo of Erdogan and Bachceli -backed by some staunchly expansionist radical officers– envision for the country in 2023, its centennial as a republic. The goal is “Turkey made great again”, with permanent footholds in Iraqi Kurdistan, Syria, large chunks of the Eastern Mediterranean seabed, and Libya.

MAVI VATAN: “Mare Nostrum”

The coining of the term “Mavi Vatan” (Blue Homeland) ultimately represents more than an act of political branding. Within the framework of its new energy (in)security architecture owing to the emerging trilateral partnerships in the Eastern Mediterranean, which it feels threaten its own efficient exploitation/transmission of the gas discoveries, Ankara is increasingly anxious. As a result, it is clear that Turkey has now adopted the strategy developed by arch-nationalist army officers. As a first step, this new doctrine envisages the domination of the Aegean Sea, of most of the Mediterranean and of the Black Sea. To this end, Turkey has invested in expanding both the size and sophistication of its navy, as well as its drillships and exploratory vessels. This highlights the extent to which Turkey has strengthened its military under the ruling AKP, which has been in power since 2002. What the “Mavi Vatan” turn means for the future of Turkey’s participation in NATO, or Ankara’s relationship with its Western partners, is far from clear. There are, however, two real dangers ahead:

The first is a possible confrontation with Greece which, like Turkey, has been a member of NATO since 1952. The “Mavi Vatan” doctrine makes it clear that Turkey does not recognize the Lausane Treaty’s arrangements over the Aegean. Turkey claims many Greek islands and Greece’s EEZ. There have been threats about drilling for gas near the Greek island of Crete and Kastelorizo. Flushed with confidence after his victories in Syria and Libya, President Erdogan has remained steadfast in spite of threats of sanctions and increased diplomatic isolation. It is possible that he may well decide this is a good time to challenge Greece, especially as such an exploit would play well at home.

The second danger lies in Libya: Arguably the most striking demonstration of “Mavi Vatan” worldview can be seen in Turkey’s evolving policy towards it. Turkey has its own ties to Libya, as well as economic and geopolitical interests that go beyond this regional competition.

In December 2019, Ankara signed a MoU with representatives of Tripoli’s government. The agreement, which charted a mutually expansive maritime border between the two states, has been heralded across Turkey’s political spectrum as a triumph in the name of the country’s “Mavi Vatan”. Until January 2020 Turkey is recorded to have sent 100 of its officers and at least 2,500 militants from jihadist groupes operating in Syria under the orders of MIT, the Turkish Intelligence Service, who quickly overturned the military result on the ground against General Haftar.

Ankara makes no secret of wanting to establish a naval and an airbase on Libyan territory. Along with any attempt to expand the GNA-controlled zone by moving toward Sirte, these bases could trigger a more forceful Egyptian reaction, possibly supported by Algeria and even the Russians, UAE and possibly France. A new crisis, therefore, is brewing and unless Washington starts paying attention, it could mutate into yet more, wholly avoidable, long-term discord.

In the mind of Recep Tayip Erdogan

Domestic economic and political considerations are certainly at play in President Erdogan’s aggressive foreign policy, with public disquiet over Turkey’s struggling economy brewing and the strength of the political opposition building, while COVID-19 reaps unknown numbers of lives. His regime needs constant action to hide what is happening really inside the country, and it is very happy to see discussions about the victorious Turkish army running around the world, as a distraction.

The economy of Ankara is on the verge of collapse

Inescapable as death and taxes, with the arrival of summer Turkey has plunged into its cyclical currency crisis. This time, however, the epilogue could be different from that of 2018 and especially last year, when it was the billions of Beijing -headed by an old swap miraculously went to the collection with Swiss punctuality – to save the Ankara Central Bank from the bleeding of its foreign reserves in an attempt to defend the lira from speculative attacks.

Today, in fact, not only the country is in far worse financial conditions than those of the recent past but, above all, COVID-19 is bringing the tourism sector to its knees, one of the few that can guarantee tax revenues. In short, the strong risk is that Turkey will fall into a state of absolute instability .

Speaking last month, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan hailed a sharp fall in interest rates and praised measures taken to block “malicious” attacks on the Turkish lira. Such steps, he said, were “strengthening the immune system of our economy against global turbulence.”

That could not be further from how most economists see the Turkish picture. The collapse in tourism as a result of the coronavirus pandemic has left a gaping hole in the country’s finances. Foreign investors have fled, pulling out almost $13bn from the country’s local-currency bonds and stocks over the past 12 months.

In the face of those outflows, the country has burnt through tens of billions of dollars of reserves this year in a bid to maintain an unofficial currency peg -a move that marks a rupture with a two-decade policy of allowing a free float. But, in a sign that those efforts are floundering, the lira has lurched towards a record low against the dollar, even as authorities spent billions trying to defend it.

Inflation and external vulnerabilities remain high in Turkey, made worse by currency weakness, while the economy is expected to contract this year, Moody’s said in an annual report: “The potential for renewed geopolitical tensions and prolonged stagflation are factors that could lead to a repeat of the 2018 currency crisis or more challenging conditions,” the ratings agency said. Concerns among investors about policy direction and transparency have resulted in further depletion of the central bank’s foreign currency reserves this year, increased dollarisation of the economy and a weaker lira, Moody’s said.

The lira hit a record low of 7.269 per dollar in early May, prompting the government to do a deal with regional ally Qatar for $10 billion in currency swaps. Turkey’s attempt to prevent the lira from sliding “risks pushing the country into a financial and balance of payments crisis,” the editorial board of the Financial Times said.

Inflation has accelerated to 11.4 percent, significantly higher than the central bank’s benchmark interest rate of 8.25 percent, as the government sought to stimulate the economy with cheap lending from state-run banks.

Turkey’s junk ‘B1’ sovereign credit rating, which carries a negative outlook, would probably be downgraded should the authorities fail to pursue an effective policy framework that supports external funding needs, mitigates pressure on inflation and puts the country on a sustainable path of economic growth, Moody’s said.

Turkey’s banking system has $48.5 billion of short-term wholesale funding coming due over the next 12 months, making banks vulnerable to constrained market access.

President Erdogan, however, is the master of creating crisis, using the weaknesses in his antagonists, duping rivals, employing divide and rule policies. It seems that mr. Erdogan saw the 4th anniversary of the attempted coup as a symbol for launching a series of acts that aim to cement his power. Above all, his equation is simple: In order to survive politically, he has to constantly raise the stakes in a daredevil gamble. He may or he may not, however, the Turkish President is focusing on headline-grabbing issues, in an attempt to captivate the minds of his electoral base. The only thing likely to erode that base of support would be a large number of Turkish personnel killed in his overseas adventures, or/and a major geopolitical defeat that cannot be hiden.

The move to turn the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque, against all odds, signals plans for a snap election. Turkey’s strongman u-turn from his last year’s opposite stance, points to uncertainety, to say the least, ahead of the next general elections scheduled for 2023. Polls increasingly show Turkey’s new political parties founded by former Erdogan allies, eating away at the support his ruling AKP had.

Erdogan’s declaration is meant to serve as a national boost at a time when Turkey is in an extremely precarious political and fiscal position. Turkey has waded into the Syrian quagmire, it has the Kurdish problem to contend with, it is conducting risky adventures in Libya, and it is stirring unrest in the Eastern Mediterranean. In Erdogan’s view, turning Hagia Sophia back into a mosque is a Turkish victory and a source of national pride during a time of great turmoil.

To Erdogan and Csavusoglou, Hagia Sophia is evidence of Turkish Muslim hegemony over the Muslim world. Its transformation into a mosque emphatically declares that position. Is the timing of this move with the anniversary of the aborted July 2016 coup accidental?

The fact of the matter is, the foreign policy he has helped shape will offer more problems than solutions in tackling the current world, as well as Turkey’s, disorder. President Erdogan calls it “forward defence” -fitting the policy line his partner Bachcheli has been advocating all along- and coins another key expression: “Military first”. The trio of traditional Turkish military might, its recent technological advancements (drones, airlift capabilities, professionalised army, its modernised fleet) and effective use of Islamist fighters in the form of mercenaries or as proxies, proved a formidable force in overturning the balance of forces on the ground. Turkish victories in Syria and Libya, however, have been made possible mainly by Washington’s and Europe’s unwillingness to stand up to mr. Erdogan, which only feeds his sense of invincibility.

President Erdogan knows that Westerners are now obsessed with “China in Africa”. He therefore thinks they will keep quiet while Turkey takes the big piece of Africa not yet fully colonized by China.

Turkish Navy and Air Force

Currently, Turkish navy ships have been a constant presence off the Libyan coast. To help ensure GNA’s victory, Turkish vessels are thought to have given sensor support to Turkish drones as they attacked Haftar’s LNA and destroyed Russian Pantsir air defense systems backing him. Vessels that Turkey has already deployed in the Mediterranean have also been busy escorting cargo ships to Libya loaded with arms and supplies for fighters in Tripoli.

The main Turkish naval units are 16 frigates: 8 ex-US Oliver Hazard Perry class, 4 MEKO 200TN Block I and 4 MEKO 200TN Block IIA/B, 9 Corvettes: 3 ADA class built in Turkey under the MILGEM National Ship Program, and 6 D ‘ESTIENNE D’ORVES class of French origin, 12 submarines: 4 Type 209/1200 (2 upgraded), 4 PREVEZE class Type 2009T1/1400 and 4 GUR class 2009T2/1400 mod and 21 missile boats. \par

The 8 ex-US Oliver Hazard Perry class frigates were delivered in 1998-2001. They are the only naval assets with an area air defence capability equipped with SM-1R mid-range anti-aircraft missiles. The 4 Track IIA/B frigates of German origin entered service during 1995 to 2000. The four MEKO 200 Track I frigates, also of German origin, entered service during 1987-1989. The three Turkish-built ADA class MILGEM corvettes, entered service during 2014-2018 and the 6 D ‘ESTIENNE D’ORVES’ class were acquired second-handed from France during 2001 to 2002. Deliveries over the past decade have included:

- 4 ADA class MILGEM corvettes

- Completion of the modernization program for 4 GIRESUN class frigates (formerly Oliver Hazard Perry class). This involved the installation of a ESSM RIM-162B missile Mk 41 vertical launch missile system (22 km range), retaining the Mk 13 launcher for the SM-1MR missiles (37 km range) and installation of a new GENESIS combat system.

- Completion of a modernization program for the Track II A/B frigates. This entailed the installation of two Mk 41 vertical launch system 8 cell modules and replacement of the Mk 29 Mod 4 rotating launcher, installation of a new 3D SMART-S Mk2 air and surface surveillance main radar and installation of a new GENESIS Combat Management System.

- Completion of the modernization program for the 2 type 209/1200 submarines with the installation of the American Raytheon INS system, German Zeiss periscopes and the underwater version of the ARES-2 electronic support system (ESM) by Turkish-Aselsan.

- The first type 214TN AIP submarine “Reis” was comissioned in early 2020.

Under construction today are: - The first (out of a planned acquisition of four) Turkish-built ISTANBUL class frigates under the MILGEM national ship program. Estimated delivery of the first ship is in 2021.

- 5 type 214TN AIP “Reis” Class submarines although the program is suffering from major delays. Deliveries are planned of one per year for each new submarine until 2025.

- An ANADOLU class “Mistral” aircraft-helicopter carrier, (planned of carrying 6 F-35B (VTOL) fighters, however their delivery was canceled due to the rejection of the whole F-35 project, over the S-400 dispute with USA), 4 attack, 8 utility and 2 anti-submarine helicopters.

The Turkish Air Force’s major fighter aircrafts belong to 2 main types: F-16 and F-4. Deliveries over the last decade were of 30 F-16 Block 50+ Advanced during 2011-2012. In 2005 it was planned to upgrade 162 F-16 aircraft (99 Block 40 and 73 Block 50) to F-16 CCIP (Common Configuration Implementation Program) standard. Their capabilities are almost identical to those of newly-acquired F-16 Block 50+ Advanced. Also being structurally upgraded since 2015, are 35 F-16 Block 30 that are currently further modernized.

During 2001-2003 Turkey completed the upgrading of its F-4E aircraft to F-4E 2020 Terminator standard. Today, 42 aircraft of this type are operational. The Turkish Air Force has 4 E-7A (737-700) Peace Eagle AEW&C aircraft (delivered 2014-2015), and 7 KC-135 Stratotanker Aerial refuelling aircraft that were delivered used from the USA during 1995-1998.

Turkey participated in the production program of the stealth F-35 and ordered 100 fighters. However, Turkey and the United States have been at odds over Ankara’s purchase last year of the S-400s, which Washington maintains are incompatible with F-35 technology. On the heels of the delivery, the United States cut Turkey’s participation in the F-35 fighter jet programme. The U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee has authorised the U.S. Air Force to withhold six F-35s fighter jets originally delivered to the Turkish government, but never left the U.S. soil, that were sold to Turkey after modifications.

President Erdogan announced last November that Turkey’s TF-X 5th generation fighter jet would be ready for flight in the next five or six years. However, Turkey’s inability to produce a fully indigenous engine is affecting the project’s progress.

EGYPT: Armed and ready…

Egypt has the largest gas reserves in the region, at 75.5 trillion cubic feet. Zohr’s discovery was catalytic as it confirmed that, the region of the South East Mediterranean contains huge deposits of natural gas. The above discoveries have been combined with the existense-exploitation of additional deposits in the Egyptian EEZ, more specifically in the wider maritime region outside the vast Nile Delta. Italian Eni is especially strong in Egypt, where it operates the supergiant Zohr field and others. BP is also well positioned in the country. Egypt already has two major LNG terminals in the Mediterranean, the Idku (east of Alexandria), where the gas pool of Shell, Texas-based Noble Energy Inc. and Israel’s Delek Drilling LP continue to hammer out a contract to service the liquefied natural gas plant, and Damietta (west of Port Said).

Tensions between Turkey and Egypt have been high in recent years, as Erdogan has sought to delegitimise the Sisi regime, which came to power after the ouster of Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi in 2013. Egypt, Greece, France, and the UAE have made efforts to create a grander pro-Haftar coalition involving Tunisia and Algeria. When this failed, they doubled down on the EMFG grouping, and in May released another joint denouncement of Turkey’s interventions in the region. President Erdogan’s direct help to al-Sarraj, with weapons and with anti-Assad fighters, tilted the balance in favor of the GNA. Its forces reached the outskirts of the cities of Sirte and Jufra, which demarcate the line separating the belligerents. Egypt is alarmed by this success and is seriously considering a military intervention.

Both Egypt and Turkey, however, are close allies of the United States. President Donald Trump is not interested in a crisis on the eve of the presidential elections, and has asked both leaders to calm down. Furthermore, there are a lot of major stakeholders who do not need a shooting war in the Eastern Mediterranean and/or the Middle-East. After all, if it came to a true military confrontation between Turkey and Egypt, then you can be pretty sure that NATO, CENTCOM, Israel and Russia would all have major concerns.

Earlier this month, Egypt said that part of a seismic survey planned by Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean potentially encroached on waters where Cairo claims exclusive rights. Ankara’s most recent steps was a major factor that accelerated the signing of the maritime agreement between the two countries, designating an EEZ in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Egyptian Navy and Air Force

The main Egyptian naval units are: 2 French built “Mistral” classhelicopter carriers – amphibious assault ships, 8 submarines, 9 frigates, 4 corvettes and about 45 missile boats. Deliveries over of the past decade have included 3 German class 209/1400 submarines with one remaining, 1 French Fremm class frigate, 1 French Gowind class corvette and a second-hand Pohan G class corvette of South Korean origin.

Moreover, Italian sources reported that Cairo plans to sign with Italy the largest military deal with a European country worth about €10 million ($11.2 million), including two Bergamini-class FREMM frigates, which are ready since they were originally built for the Italian navy, in addition to four other frigates that will be built specifically for Egypt.

The Egyptian Air Force’s major fighter aircraft belong to four main types: F-16, Mirage 2000, Rafale and F-35. Specifically, Egypt has ordered 24 French Rafale fighters, deliveries of which begun in mid-2015 and currently 14 aircraft are operational. That same year the country also ordered 46 MI -35, of which 15 have been delivered and are already in operational use. Egypt also uses 18 Mirage 2000, 40 F-16 C/D Block 32 delivered in 1986-1988, 138 F-16 C/D Block 40 delivered in 1991-2002 and 20 F-16 C/D Block 52 delivered between 2013-2015. Finally, the Egyptian Air Force also has 9 E-2C Hawkeye 2000 AEW&C aircraft, which were upgraded to the 2000 edition during 2003-2007.

On March 18, 2019, the Egyptian Air Force inked a $2 billion deal to buy 24 Russian-made Su-35 fighter jets, including related equipment, according to Egypt’s State Information Service (SIS), that reported back then that the deal entered into force in late 2018, and the fighter jets will be handed over in 2020-2021, with the first five reportedely being already delivered. The jets will be added to the Egyptian Air Force’s list of Russian-made weapons, including the Mikoyan MiG-29M, Ka-52 Alligator and S-300VM “Antey-2500”.

GREECE: Implementing Red Lines…

Greece is a rather newcomer to the “Energy Game”, however with great prospects of becoming energy hub. On January 2 Greece, Cyprus and Israel signed an InterGovernmental Agreement for the EastMed natural gas pipeline in Athens. Its geopolitical/security perspective is crucial. Especially Article 10 of the agreement that contains provisions on measures to protect the pipeline. The relevant provisions are considered very important, as such clauses are not included in similar agreements.

Moreover, this year the TAP Pipeline, is expected to start. ExxonMobil too, has a partnership with Total and Hellpe for exploration south of Crete. And ofcourse the FSRU in Alexandroupolis, which is particularly important to unlocking the Balkan energy island and expanding opportunities for exports into Greece of LNG, as well as for all of the countries to its north, that are 100% dependent today on Gazprom and Russia’s use of energy as a political weapon. Greece is an important key to unlocking that situation.

Greece lives in a complicated neighborhood vis-a-vis Turkey; but also a complicated neighborhood vis-a-vis North Africa and the Magreb, the refugee problem and the Eastern Mediterranean. Greece is back in terms of the Eastern Mediterranean. You see that in the thriving Greece-Israel relationship, the very successful Greece-Israel-Cyprus Trilateral, as well as the Trilateral of Greece-Egypt-Cyprus, which was the basis for the formation and the eventual signing of the Agreement that partialy delimites the EEZ between Greece and Egypt.

The “Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act of 2019” allows the U.S. also to fully support these trilateral partnerships, through energy and defense cooperation initiatives, essentially upgrading the geopolitical roles of Greece and Cyprus. In this respect, Greece is also obliged to defend Cyprus from any attack by Turkey, as formalised in the 1993 Greece-Cyprus joint proclamation of Single Area Defence Doctrine. Athens has clearly stated that it will support the Republic of Cyprus in any way has requested this support, for example by imposing further sanctions against Turkey or/and by any other means if necessary.

It is this upgraded geopolitical role, especially the expansion of military cooperation between the United States and Greece, which Ankara cosniders it could stretch the US-Turkey relationship even more. The US and Greece last year signed the revised Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement, providing for increasing joint US-Greece and NATO activity at Larissa, Stefanovikio, and Alexandroupoli’s port as well as infrastructure and other improvements at the Souda Bay naval base in Crete. (see: Big U.S. investments in strategic sectors of mutual benefit). In this respect, Turkey eyes suspiciously that:

- The Pentagon has activated the use of military bases and facilities in Greece’s northern port city of Alexandroupoli amid rising tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly after Ankara issued a Navtex for seismic surveys in a sea area between Cyprus and Crete.

- The remarks by US Ambassador to Athens Geoffrey Pyatt who sided with Greece over the contentious maritime boundaries agreement signed between Turkey and Libya, by saying that all Greek islands, regardless of size, are entitled to continental shelf and exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

The Greco–Turkish frictions

After 1923 Greece and Turkey determined their place in the international system mostly through the prism of their bilateral relations. This was a result of Turkey’s longstanding decision to remain anchored to the West and to Europe. Greece was a key factor in these ties. The situation changed under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Greece is no longer the main priority in Ankara’s foreign policy. Turkey is now viewing Greece with the logic of the old Ottoman Empire: Greece is too big to ignore and too small to pose a threat. In fact, Greece annoys Turkey because it is influencing EU-Turkey relations, while potentially verging into Turkey’s area of interest.

Athens from its part, wants its European Union partners to prepare “crippling” economic sanctions for use against Turkey if it goes ahead with its planned offshore gas and oil exploration off Greek islands. Athens says that the EU is Turkey’s biggest trading partner. If it wants, it can create a huge problem for the Turkish economy.

Greece and Turkey have been engaged in an “exploratory dialogue” for 20 years now and the positions on both sides have been fully clarified: Greece wants its disputes with Turkey to be resolved on the basis of the International Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which favors Greek positions, while Turkey wants to circumvent International Law, which it has not endorsed -precisely because International Law does not favor Turkish claims. It is obvious, therefore, that Turkey has been relentlessly pursuing the policy of pressure, the strategy of coercion and the diplomacy of brinkmanship in order to create the conditions that could lead to a military incident and then seek to hold negotiations “with the gun on the table.”

In a world that says, “Do not fight, talk!” in every possible tone, Greece and Turkey are expected to hold talks, and they should indeed. On one condition: that Turkey is willing to talk. However, the road to dialogue between the two countries has been littered with more obstacles: with the presence of the “Barbaros” in Cyprus’ waters and in statements made by Erdogan that Turkish plans in the Eastern Mediterranean will continue “until the end.”

Talks could, under certain conditions, lead to negotiations. Greece would enter talks on the condition that the only issue to be negotiated is continental shelf and EEZ delineation in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Turkey, on the other hand, has been raising a wide range of issues. These include Ankara’s claims to several Greek islands, the Muslim minority in the northern region of Thrace, the demilitarization of the eastern Aegean islands and, most important, Turkey’s joint exploitation of Greek and Cypriot resources -in Turkey’s view, Greece and Cyprus are one, and in a way they are.

Greece & Turkey have come to the brink of war 3 times since 1974

Long-simmering tensions between NATO allies Turkey and Greece have flared again. President Erdogan has long decided to end with the Greek “annoyance”. The application by Turkish Petroleum (TPAO) on May 30 for an exploration permit in the area between the Greek islands of Crete and Rhodes was tantamount to an informal ultimatum: Let’s settle all disputes between the two countries. Or, as the country’s president warned, Greece would “pay the price” of having to take on Turkey.

For now, neither appears willing to be the first to trigger a face-off in the Eastern Mediterranean and Aegean seas that would have dramatic consequences for the entire region and beyond. Yet by putting their navies on standby, the potential for further escalation is clear. Here’s a look at how the two neighbors got to this point.

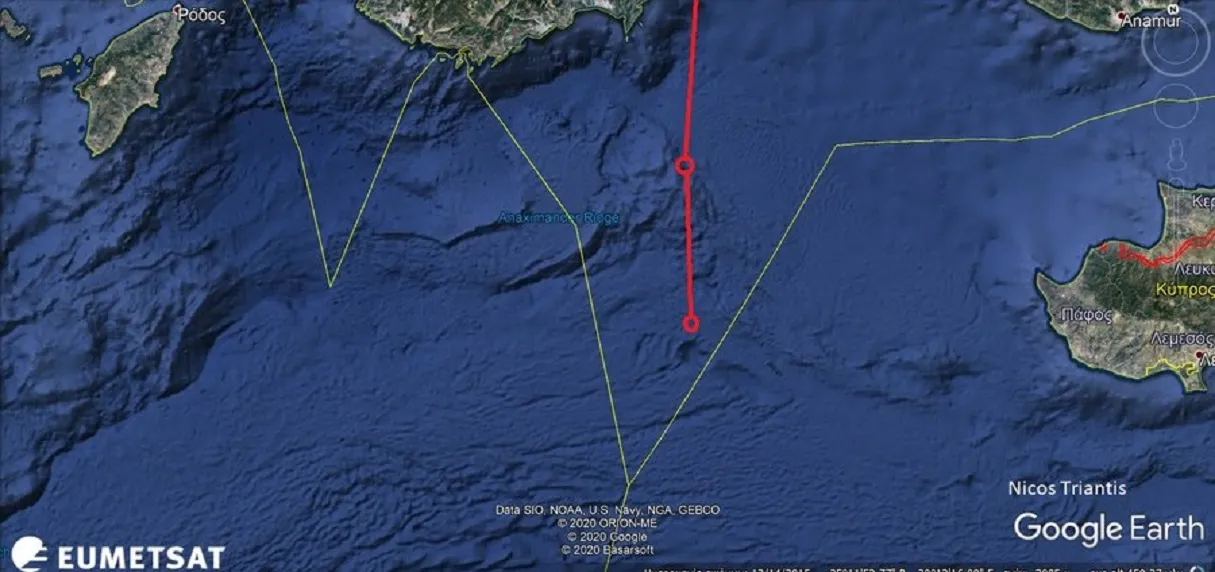

Here’s a look at how the two neighbors got to this point: On July 2, Ankara issued the contentious navigational telex for seismic surveys between Cyprus and Crete. It was a decision to accelerate and it was driven by a number of factors: the German presidency’s unusually interventionist initiatives to de-escalate tensions annoyed Ankara; the bombing of the Al-Watiya Air Base in western Libya by so-far unidentified planes; the deteriorating ties with France; the discussion on fresh sanctions against Turkey at the informal EU foreign ministers meeting in late August; and the extensive damage to this year’s tourism season due to Turkey’s exclusion from the EU’s safe travel list until August 31 due, to coronavirus concerns.

The swift deployment of the Greek fleet held back the course of events, allowing an opportunity for diplomacy. The lesson was clear. Although Turkey has been conducting similar seismic surveys within the contours of Cyprus’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ) since 2013, the violation has generated no meaningful reaction. (see: Drums of war are beating more loudly in Eastern Aegean)

In terms of the International Law of the Sea, Cyprus’ position is far stronger compared to Greece’s. Contrary to the Greek continental shelf, Cyprus’ EEZ has been demarcated with international agreements. If there was an international reaction, it was due to the risk of a hot incident and not because international law had been violated. Greece has strong armed forces and it stated that any violation of its sovereign rights would encroach on its “red lines.”

Turkey was forced to pause its activities but not to retreat. President Erdogan appeared to accept Berlin’s proposal for de-escalation. He offered to suspend the operations of the “Oruc Reis” vessel for one month and thereby make some room for negotiations. He has effectively revived his ultimatum while coming across as complying with European mandates. The concurrent announcement of exploration inside Cyprus’ EEZ demonstrates that the Turkish threat has not gone away. Furthermore, Turkey is trying to create the impression that its drilling plans inside Cyprus’ EEZ are legitimate. It was enough, for Turkey, that it has paused its activity within Greece’s continental shelf.

Time for a new East Mediterranean strategy…

At the point where things have reached, it is vital for Greece to abandon two traditional syndromes definitively and not just for the time being: First, military entrenchment within the Aegean. Secondly, understanding its foreign policy exclusively and unilaterally in EU terms. The European dimension is a given, but the events themselves have forced Greece in recent years to perceive itself as a Mediterranean power. The game in the Eastern Mediterranean, however, is played on other terms. It is not limited to the classic post-war diplomacy of cautious steps, if not inaction. Turkey is already doing that and it is promoting its status at every chance possible. Furthermore, Ankara has developed quite a degree of self-confidence in terms of its naval prowess.

Greece obviously cannot shrink away from all that. It needs to protect its own vital interests and at the same time project its influence in the wider region. Even more, because currently Turkey has made more adversaries than it can afford. Ankara has made the serious strategic mistake of “over-extension”, provoking everybody on its periphery to team together against it. Turkey in the post-war era, never had more enemies around it, never had more serious problems internally, and never projected such a negative image abroad.

An unprecedented alliance has been forged against Turkey in the region by various diverse countries such as Egypt, Israel, the Gulf Arab states (except Qatar) and France. Now Greece should be at the forefront of this anti-Turkish rally. Athens’ problem is currently how to neutralize Turkey as a bully state in our region. There are many other states that have exactly the same position.

Greek governments have sought to increase the country’s leverage by launching cooperation schemes with Cyprus, Egypt and Israel. Such initiatives have intensified in recent years, which is a welcome fact. However, they are not enouph to solve the actual problem. This is an urgent matter. Solutions do exist and they have to be examined with the maximum possible degree of political consensus.

This practically means that the most effective way for Greece to defend its sovereign rights and at the same time to avoid war -or even a hot incident- with Turkey is to take the initiative to upgrade the current trilateral schemes to a defense Mediterranean Alliance together with France, Egypt and Israel with a distinct anti-Turkish tinge. It is not an initiative with a given successful outcome, however the conditions today are more mature than ever and it is definitely worth the effort.

The “NAVTEX WAR”

Turkey issued a NAVTEX reserving an area between the Greek islands of Rhodes and Kastellorizo for gunnery exercises on Aug. 10 and 11. The Navtex issued at 11.26 a.m. on Thursday, the very day Greece and Egypt signed the maritime borders’ Agreement delimiting an EEZ between them.

Early on Monday morning Turkey issued a new NAVTEX to conduct seismic research operations over the next two weeks, with duration till August 23, south of the island of Kastellorizo for gas exploration by the “Oruc Reis”, however out of the recently delimited EEZ area between Greece and Egypt.

At the same time the surveyor vessel sailed towards the designated area, while the Turkish fleet started naval exercises in an area southeast of the islands of Kastellorizo and Rhodes, an activity announced on August 6.

Athens responded to Turkey’s decision to issue the new NAVTEX with a counter-NAVTEX, calling on all vessels to disregard Ankara’s message. The Greek Navtex said that an “unauthorized station” has broadcast a message referring to “unauthorized and illegal activity” in an area that overlaps the Greek continental shelf. All mariners are requested to disregard [the] Navtex,” the message said.

Turkey responded to the Greek counter-NAVTEX issued earlier Monday, with an advisory saying that three Turkish research vessels are “conducting seismic survey in Turkey’s continental shelf… in accordance with international law.” According to the latest Turkish NAVTEX, an “unauthorized station” has broadcast a message “in Turkish Navtex service area” refering to Greece’s earlier advisor

Amid the escalation, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis chaired an emergency meeting of the country’s top decision-making body on foreign affairs and defense matters, KYSEA, to discuss the developments. Greek Minister of State Giorgos Gerapetritis stated afterwards “We are at full political and operational readiness. The majority of the fleet is ready at this moment to do whatever is needed. Our ships that are sailing in crucial areas were already in place days ago. If necessary there will be a greater development of the fleet. It is clear that we are not seeking any tension in the region. On the other hand our determination is a given.”

Athens, although has placed its Armed Forces on high alert and monitors every tiny move of the Turkish fleet and the “Oruc Reis” surveyor ship, is weighing its diplomatic options while trying to keep channels of communication with Ankara open despite the contrary stance of the Turkish government.

The period of 11-23 August is critical…

There is the certainty that Ankara wants to test Greece’s resolve by sending the its surveyor vessel to a maritime block, overlaping its continental selfe, in an effort to de facto nulify the Greece-Egypt Agreement. TPAO’s effort to conduct energy exploration with the aid of the Turkish Navy, , is evidence of Ankara wanting to escalate tension in the direction of militarizing the crisis.

President Erdogan struggles to destabilize the region in an effort to win time, being squeezed between Turkey’s economic woes growing and the lira nosediving, the stalemate in Libya, the war fronts in Indlib, Iraq and Azerbaitzan, as well as the new status quo the Greece-Egypt Agreement establishes in the Eastern Meditarranean. The more pressure he feels on a political and geopolitical level, the more unpredictable, or even dangerous the situation will become.

Washington and Moscow, have expressed their deep concern by Turkey’s intended plans, saying that such provocative actions increase tension in the region, do not have a clear idea of how things will evolve. At the time of writting, the US State Department has condemned Turkey’s Monday announcement that it will be conducting energy exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean in an area that overlaps Greece’s continental shelf.

The European Union has also expressed its concern over the rapidly deteriorating situation, however in the same cautious and restrained tone it has been accustomed to. “Latest naval mobilisations in eastern Mediterranean… will lead to a greater antagonism and distrust. Maritime boundaries must be defined through dialogue and negotiations, not through unilateral actions and mobilisation of naval forces.” foreign policy chief Josep Borrell and other EU officials stated on the current crisi, calling the developments “extremely worrying”.

Ankara strives to subverse the current status in the region with high risk actions and statements. It was certain that the Turkish President would send the surveying ship, accompanied by warships towards the announced area, in his own time, testing Greece’s resolve to defend its declared red lines and its Allies as well. If there is no an actual accident, it is almost certain that he has already drawn his exit plan, in terms of communication to generals on one side and the Turkish public on the other.

It remains to be seen how far Turkey will push its attempts to disrupt the process of gas exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean, this time. The future direction of events is likely to depend on the extent of President Erdogan’s growing personal insecurity as well as internal and international pressure.

Nevertheless, the only thing that truly could stop mr. Erdogan from realizing his intentions is the real threat of force, or even war, from Greece as well as other states threatened.

The Hellenic Navy and Air Force

The “axis” strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean, led the Greek state to year after year dispose over 2% of its GDP in military expenditures for NATO, becoming the steadiest buyer of weapons in the euroatlantic alliance.

Greece is traditionally a major naval power. Anyone who has studied the country’s history can easily grasp that fact. No further explanation should be necessary. Meanwhile, renowned analysts have pointed out that Greece would run into trouble every time financial stress took a toll on naval spending. Today, the Hellenic Navy has found itself lagging behind due to the financial crisis. Sure, it can still fulfill its mission, however it is in urgent need of a brave modernization program. The details are known to those who ought to and who want to know. And at a time of open source information, these details are obviously not a state secret.

The main Greek naval units are: 4 “Hydra” class type MEKO 200HN frigates, of German origin, which entered service from 1992 to 1998, 6 KORTENAER “S” frigates of Dutch origin, modernized in the years 2007-2010, 3 KORTENAER “S” frigates that have not been not modernized, 11 submarines and 17 missile boats (5 British SUPER VITA, 4 modernized French Combattante III, 5 also French Combattante IIIB and 3 former German S148). Deliveries over the past decade have includes 5 AIP submarines: 4 “PAPANIKOLIS” class type 214 and a completely upgraded type 209/AIP and 2 “ROUSSEN” class, Super Vita type missile boats. Another two Super Vita boats are being built in Greece, but the program has suffered very long delays.

The Hellenic Air Force’s major fighter aircraft belong to 3 main types: F-16, Mirage 2000/2000-5 and F-4. Deliveries over of the past decade have been 30 F-16 Block 52 + Advanced during 2009 – 2010. Very recently, it was decided to modernize 85 F-16 (55 Block 52+ and 30 Block 52+ Advanced) to F-16V (AESA radar) standard. In addition, the country is modernizing 5 P-3B naval co-operation aircraft. The Hellenic Air Force also uses 17 Mirage 2000B/EGM-3 (delivered 1988 – 1992), 24 Mirage 2000-5Mk 2 (delivered 2007 – 2009), 32 F-16C/D Block 30 (delivered 1989 – 1990), 39 F-16 C/D Block 50 (delivered 1988 – 1992), and 34 F-4E upgraded to Peace Icarus 2000 standard, during 2003-2004. Finally, the Hellenic Air Force also has four Erieye EMB-145H (delivered in 2008) AEW&C aircraft.

After the exclusion of Turkey from the F-35 project the Greek government, seeking to exploit the air power void in the region (only Israeli Air Force has this type), has already submitted a “Memorandum of Interest” to explore the possibility of buying the over-expensive state-of-art American F-35 airplanes.