A geopolitical scheme which needs to evolve to a viable energy route…

The first month of 2020 is full of developments which may define the future of energy routes in South Eastern Mediterranean:

* On January 2, Greece, Cyprus and Israel will sign, in Athens, the agreement to build the EastMed pipeline.

* On January 4-5, the Foreign Ministers of Cyprus, Egypt and Greece will hold a meeting, with the added participation of France.

* On January 7 the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis will meet US President Donald Trump in Washington to discuss their two states cooperation on energy and security issues in the Eastern Mediterranean.

* On the same date, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo will travel to Nicosia where he will meet with President Anastasiades and Foreign Minister Christodoulides to reaffirm the robust U.S.-Republic of Cyprus relationship.

* Near the end of January the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis will meet with the French President Emmanuel Macron to discuss about the same issues.

Anastassios Tsiplacos - Managing Editor

On January 2, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Cyprus President Nikos Anastasiades will sign the agreement for the EastMed pipeline that will transport gas from the Southeast Mediterranean to Italy and the rest of Europe. Italy is also expected to sign the agreement at a later stage. EastMed pipeline is a huge project. If it is deemed technically feasible and economically viable, it will go ahead. There is also the prospect that East Med gas will be transferred by LNG ships. Depending on the quantities involved, the two transportation paths might prove supplementary. Italy is also expected to sign the agreement at a later stage. In any case, the message conveyed by this agreement is a loud one and its geopolitical symbolism is clear.

If geopolitics is an argument about the future world order, then the easternmost third of the Mediterranean Sea is shaping up to be a cauldron of quarreling visions and interests like no other. This region is bound to North by the coast of Cyprus, to the East by the shores of Syria, Lebanon, Israel and the Gaza Strip and to the South by Egypt. The current situation of Eastern Mediterranean gas development is still fluid, and the instability produced by the war in Syria and Libya is adding additional sources of complexity, that can undermine the projects discussed by governments and energy companies. However, the study of the interaction between markets, political and security dynamics offers a starting point for understanding strategies. In particular, the geopolitical interests of the Eastern Mediterranean countries are bound to affect geoeconomic decisions concerning flows and exchanges in traded gas. The stakeholders’ capacities however, to realize their preferred political options and use natural gas as a tool of foreign-policy objectives, are constrained by economic, technical and security concerns.

Regional Trilateral Summits’ history

Given the significant breadth of Turkish claims and its extremely maximalist positions on issues directly related to Greece and Cyprus, as well as Israel and Egypt, it was deemed necessary to formulate a comprehensive policy and to utilize the entire foreign policy toolkit: alliances, bilateral diplomatic contacts and the opening of parallel communication channels, exploring prospects for bilateral and/or trilateral economic and other cooperation, as well as sending a clear message about regional stakeholder’s red lines, while maintaining a strong capacity of deterrence.

Israel, the first country of the region to make major gas discoveries, was also the first mover in the economic and political game for its monetization, in terms of new export routes and infrastructure projects. In the following years, the Israeli, Cypriot and Greek energy ministers created joint task forces to evaluate the feasibility of several options. For exportation, they are considering the EastMed Gas Pipeline to carry gas from Israel and Cyprus to European markets through Greece, and a joint Israeli-Cypriot LNG plant near Vassilikos on the southern coast of the island. However, other projects are simultaneously being evaluated by each government according to its own energy-security agenda and national interests.

Each country has its own reasons for becoming part of this alignment, as there are converging views on energy affairs and, among the participating states, common perceptions of threat. Additionally, the creation of a pipeline that will transport natural gas from Israel via Cyprus and Greece to Europe is crucial for the continent’s energy security, as it adds to the reduction of dependence on Russian, Arab-Muslim and Iranian hydrocarbons, something that is seen positively by the US and the Western world as a whole.

The first trilateral summit between Greece, Israel and Cyprus took place on January 2016 and should be remembered for the leaders’ decision to create a committee for the planning of the EastMed, for the transportation of natural gas from Israel to Europe. In June 2017, Italy became part of this process and a working group for the supervision of the project was established. The agreement over the relevant text was achieved at the Beersheba summit of 2018. The two last summits (12/2018 and 03/2019) were actively supported by the United States, as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, for example, participated in the Jerusalem summit of March 2019.

It was the 20th of previous March when the 6th Trilateral Summit “3+1” at Jerusalem was concluded with the following statement: “Secretary Pompeo underlined U.S. support for the trilateral mechanism established by Israel, Greece and Cyprus, noting the importance of increased cooperation; to support energy independence and security; and to defend against external malign influences in the Eastern Mediterranean and the broader Middle East,” affirming “…their shared commitment to promoting peace, stability, security and prosperity in the Eastern Mediterranean region.” This resolution raised hopes high about the prospects of establishing a safe and prosperous environment for the exploitation and export of regional hydrocarbons’ sources, especially those of Israel’s and Egypt’s, to the “energy thirsty” Europe.

Then followed the 1st Ministerial Energy Summit, in Athens on August 7, encouraging regional cooperation energy projects. Meeting in Athens, the energy ministers of Greece, Cyprus, and Israel -Kostas Hatzidakis, Georgios Lakkotrypis, and Yuval Steinitz, as well as US Assistant Secretary of State for Energy Resources Frank Fannon- discussed their cooperation in the field of energy, while affirming their shared commitment to promoting peace, security, and prosperity in the Eastern Mediterranean region. During their meeting in Athens, the four Energy Ministers reaffirmed the support of their countries for the implementation of the EastMed gas pipeline, a project of major significance for the energy security of the EU that also establishes a strategic link between Europe and Israel.

The second major regional trilateral is between Egypt, Greece and Cyprus. During their 6th Tripartite Summit, at Elounda Crete back in October 2018, the leaders of the three countries certified their strategic co-operation that enhances the security, stability and prosperity of the Southeastern Mediterranean region. In addition they signed the agreement on the construction of the underwater pipeline that will start from the sea area within the Cypriot EEZ, transferring the natural gas from Cypriot Plot 12 “Aphrodite” to Egypt, which has the necessary infrastructure to process and convert it into LNG, with the aim of exporting it to Europe.

Unlike previous trilaterals, which focused on all the issues of cooperation between the three countries, the 7th Trilateral Summit on October 8th in Cairo, aimed at forming a strong energy-based alliance in the East Mediterranean. The energy dossier, particularly natural gas, was of utmost importance at the summit, in addition to bilateral trade and investment relations. The joint declaration stated that the three countries underlined the importance of making additional efforts to boost security and stability in the region, and strongly called on Turkey to “end its provocative actions” in the Eastern Mediterranean condemning them as “unlawful and unacceptable”, including exploring for natural gas in Cyprus’ territorial waters, which they called “a breach of international law.”

Soon after the Summit in Cairo, Cyprus and the Aphrodite consortium signed an exploitation license and a revised production sharing contract, aiming to start natural gas production in 2025, generating projected revenues of $9.3 billion for a period of eighteen years. The 25-year exploitation licence is the first of its kind signed with Cypriot EEZ licensees and it’s based on the final development and production plan of “Aphrodite”. Shell will be the buyer of Aphrodite’s natural gas.

On the basis of the plan, the natural gas from “Aphrodite” will be transferred via a subsea pipeline to Egypt’s Idku LNG plant from where it will liquified and exported to European and international markets.

Apart from the tripartite alliances, Eastern Mediterranean countries have agreed to create a regional gas market in an effort to transform their part of the Mediterranean into a major energy hub. Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Territories founded on January 14th a forum to ensure supply and demand, cut infrastructure costs and offer competitive prices. The East Med Gas Forum (EMGF) is undoubtedly a welcome development. Even though it is a political arrangement, it can but only contribute to cooperation in the region. Natural gas could be crucial to the future of East Med countries and any such initiatives that could promote its development can only be helpful. All countries around the East Med can benefit. Gas export projects could benefit from such cooperation, especially with regards to ensuring a conducive, regulatory environment, putting in place the required intergovernmental arrangements and removing political risk.

The US “East Med Act 2019” as a catalyst…

The “Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act of 2019”, will allow the U.S. to fully support these trilaterals through energy and defense cooperation initiatives. The bipartisan legislation also seeks to update U.S. strategy in recognition of consequential changes in the Eastern Mediterranean, including the recent discovery of large natural gas fields, and a deterioration of Turkey’s relationship with the United States and its regional partners. It also requires the Administration to submit to Congress a strategy on enhanced security and energy cooperation with countries in the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as reports on malign activities by Russia and other countries in the region. This legislation essentially upgrades the geopolitical roles of Greece and Cyprus. Considering the high priority given to the region, the Act also suggests that the trilateral alliance between Greece, Israel and Cyprus could serve as vehicle for the new dynamic in the region.

Nevertheless, although US President Donald Trump signed the appropriations bill that includes the “Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act of 2019”, according to reports, he objected to several articles of the bill, including parts of the EastMed Act and particularly with regards to Congress’ authority over issues of military assistance and participation in international forums (for more see “NATO in the Eastern Mediterranean: The haze of Energy War”).

With this Act, Washington is formally conveying the message that it is no longer basing its strategy in the region having Turkey at the forefront, but that it is investing in the area of diplomacy and energy on the trilateral cooperation scheme comprised of Greece, Cyprus and Israel, which is acquiring a vital role in the formulation of the US security policy in the region. Athens, Nicosia, as well as American supporters of the East Med Act point out that this law, which also stipulates the lifting of the embargo on the supply of American weapons to Cyprus, is not some kind of anti-Turkish move but rather reflects the new reality of multilevel cooperation that the US has with credible partners such as Greece, Cyprus and Israel, and western-oriented Arab countries like Egypt and Jordan.

The EastMed pipeline: A modern dream in an ancient region

The Eastern Mediterranean (EastMed) Pipeline Project refers to the construction of an offshore/onshore natural gas pipeline that connects directly Eastern Mediterranean gas resources of Cyprus and Israel to Western Greece via Cyprus and Crete. The fulfilment of the Project demands the additional construction of The Poseidon Pipeline that will connect Epirus Region (North Ionian Sea) with the Italian Region of Otranto. The project is being currently designed to transport up to 16 b.c.m./year through 1,300 km of offshore pipeline and 600 km of onshore pipeline, from the off-shore gas reserves in the Levantine Basin, of Israel (Leviathan Field with a capacity of 476 b.c.m.), Cyprus (Aphrodite Field/Block 12 with a capacity of 165 b.c.m.), as well as from potential gas reserves in Western Greece and Southern Crete.

The EastMed project is comprised of:

-200 km offshore pipeline stretching from Eastern Mediterranean sources to Cyprus

-700 km offshore pipeline conencting Cyprus to Crete island

-400 km offshore pipeline from Crete to mainland Greece (Peloponnese)

-600 km onshore pipeline through Peloponnese and Western Greece

At first glance the EastMed project is an impressive idea. The pipeline shall transport 10 b.c.m./year of gas from Eastern Mediterranean gas fields, to Greece and Italy. About 1,900km long, and reaching depths below 3km, it will be the world’s longest and deepest subsea pipeline. The estimated cost is €806.2 billion.

On Monday 3 April 2017, the energy ministers of Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Italy met in Tel Aviv, warmly watched by the EU Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy. They gathered to sign a preliminary agreement to advance the EastMed pipeline. The agreement between the four countries has created a common route on three levels: commitment to a transnational agreement, negotiations at a technocratic level that will have elements corresponding to those of the Cyprus – Egypt agreement and the presentation of the study by the contractor. The co-Understanding Memorandum that was signed between the four countries consolidated their energy role in the project, but also upgraded them politically, strengthening them on the geopolitical chess board. It is evident that the EastMed does not represent a simple gas supply pipeline, but a comprehensive strategic plan involving capital and other means, as well as the creation of security conditions in the region.

However, export of gas from the Eastern Mediterranean is a particularly thorny area. The region has seen significant resources discovered in the past decade, such as Tamar and Leviathan in Israel, Aphrodite in Cyprus and Zohr in Egypt, but there are multiple conflicting demands and pressures. They count among them the need to supply the local market, uncertainty over the capacity of existing infrastructure, regional political constraints and, finally, the need to accommodate future exploration discoveries. So, what is the business case for the EastMed pipeline? Justifications include the ability to off-take and supply gas at multiple locations along the line, energy security and a geopolitical desire to tie together countries in mutually beneficial projects. No wonder the EU is interested in its becoming reality.

European dilemmas and decisions

The EU position with regard to Eastern Mediterranean gas developments is rather ambiguous. On the one hand, the discoveries in Cyprus, a member state, will directly affect the balance of its internal energy reserves. The resources in the Eastern Mediterranean could improve economic recovery in Cyprus and Greece, two of the most vulnerable Eurozone members. Furthermore, Levantine energy resources could, in theory, if additional gas fields are found, become an important means of diversifying gas supplies and reducing EU dependence on Russia. Actually, under the 2015 PCI scheme, the EU granted to the East Med Gas Pipeline promoters a financial contribution of €802 million, covering 50% of the feasibility study of the future pipeline. On the other hand, the EU has proved to have scarce leverage to back up its policy preferences in this region, especially where national imperatives dominate the decision-making process, in non-EU member states such as Israel and Turkey.

Despite these evident limits in the EU’s energy-security strategy, it also has a wider direct political interest in solving the Cyprus question and promoting regional stability. The refugee crisis too, triggered by the Syrian civil war, and the complex relations with Erdogan’s Turkey, are becoming contentious issues capable of destabilizing the EU and fueling euro-sceptic movements. For these reasons, a scenario characterized by a possible Israel-Cyprus-Turkey energy agreement with U.S. support, would also be welcomed in Brussels, even if this development could mean that additional gas reserves discovered in the Levantine Sea would pass through Turkey before going to the EU market, thus reinforcing (sic) Ankara’s role as a crucial transit state for EU energy diversification from Russia.

There are, however, different views inside the EU: given that the East Mediterranean region constitutes a credible alternative source with the potential to help EU diversify its energy sources and reinforce its supply and energy security, it would be wise for Europe that the Fifth Corridor of gas, namely the proposed EastMed, is not transported via Turkey, as the Fourth Corridor gas (TANAP and TAP pipelines), otherwise EU energy security will be compromised. Furthermore, given that Cyprus, as an EU and Eurozone member, has already proved its usefulness to Europe various fields, in view of the explosive situation in the Middle East and urgent need to combat terrorist attacks, Brussels utterly needs the alternative EastMed energy security advantage for itself. Indeed, Cyprus constitutes the easternmost defense bastion and border of Europe.

For the EU, the materialization of an Eastern Mediterranean gas hub, understood as a crossroads of physical flows, not as a trading platform, based on Cyprus-Greece resources and Egypt’s LNG infrastructure, would be beneficial for both energy and foreign policies considerations, and could help EU to avoid becoming hostage to either Russia’s monopolistic visions or Turkey’s regional aspirations. European Union planning and decisions related to natural gas discoveries in the Southeast Mediterranean include:

- The opening of the Southern Gas Corridor. Its purpose is to extend gas transport infrastructure from the Caspian basin, Central Asia, the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

- The development of the Mediterranean Hub. Its purpose is to diversify energy routes as well as sources of supply. The Mediterranean region, given the huge production prospects of Algeria’s natural gas and the new East Mediterranean gas fields, can play a key role as a new source, but also as a new supply route.

Within the context of the decision to open the Southern Corridor, as well as the development of the Mediterranean Node, the European Commission included in November 2017 in the list of Projects of Common Interest (PCI) the following:

– Cluster Infrastructure to bring new gas from East Mediterranean gas reserves (no. 7.3) including Pipeline from the East Mediterranean gas reserves to the Greek mainland via Crete (currently known as EastMed Pipeline) with a metering and regulating station at Megalopolis and dependent on it the following PCIs:

- Offshore gas pipeline connecting Greece and Italy (currently known as Poseidon Pipeline) no. 7.3.3

- Reinforcement of the South – North internal transportation capacities in Italy (currently known as Adriatica Line)

Finally, within the framework of the Southern Corridor the program (no. 7.5) for the development of natural gas infrastructure in Cyprus (currently known as “Cyprus Gas2EU”) has also been included. In the wider context of energy transfer, the programme Priority Corridor North-South Electricity Interconnections in Central Eastern Europe (NSI East Electricity), which includes the Cluster Israel – Cyprus – Greece (currently known as “EUROASIA Interconnector”) has been included, which comprises:

- No. 3.10.1: Interconnection between Hadera (Israel) and Kofinou (Cyprus)

- No. 3.10.2: Interconnection between Kofinou (Cyprus) and Korakia, Crete (Greece)

- No. 3.10.3: Interconnection between Korakia, Crete and the Attica region (Greece)

Why not LNG?

Capital costs will remain a big driver and the potential to utilise spare capacity in existing LNG facilities in Egypt, assuming political and commercial issues can be overcome, creates a significant advantage for LNG. In addition, the costs of mega-projects have a habit of increasing and there are some tough issues around all intergovernmental agreements the division of costs, revenues and tax receipts/reliefs to be negotiated. Undoubtedly, this would be a mammoth task for the region to overcome.

With all this in mind, it is not surprising that grand pipeline schemes often don’t get built. Examples of pipeline plans that have not come to fruition and it is doubtful they ever will, include the Iran-Iraq-Syria gas pipeline and the Basra-Aqaba line. There are exceptions, of course. A system in the region that did get built as planned was the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BCT) oil pipeline, a good example of a pipeline driven by politics and security of supply. BCT was competing with proposed expansion projects and thus was difficult to negotiate and expensive, but is now an important fixture in global oil infrastructure. There are also examples of pipelines successfully operating in parallel with other offtake routes, for example the long history of concurrent operation of LNG and gas pipelines from Algeria. LNG provides access to a greater range of markets and the volumes of gas in Algeria were sufficient to force a diversification of outlets.

Back to economics…

Nevertheless, the proposed EastMed gas pipeline face headwinds. It is mainly a political driven project and even though the formation of EMGF can provide it with strong and concerted political support, it is not enough. The project still needs to secure buyers in Europe for its gas and companies prepared to invest in it,. That may happen only if it can deliver gas at prices that can compete with existing low prices in Europe. With global economic growth slowing down and ample global supplies, gas prices are trending even lower. This is a challenge for expensive-to-develop East Med gas projects. Gas exports from Egypt’s LNG plants, Idku and Damietta, are possible because liquefication costs are low.

The question is whether there is the prospect of sufficient gas to underpin a 12-15 b.c.m. line across the Mediterranean at a competitive price. Probably not yet. Or at least not enough to keep the line full for a significant proportion of its operating life.

This depends on markets that control demand and prices, so that companies can provide the required investment and technology to enter into purchase, sales, and construction contracts. Political intentions alone will not move projects forward. Therein lies the true challenge: East Med gas is expensive to develop and global gas prices are and will remain low, making exports difficult. Europe has plentiful supplies of cheap natural gas at prices this pipeline would not be able to compete with. Not to mention that during 2020 the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) from Ajerbaijan’s “Shah Deniz”, via Turkey’s TANAP, together with the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IBG) and the Turkstream 2 from Russia through Bulgaria, shall begin their operations and will flood Central Europe with natural gas.

The agreement to be signed on 2 January is an intergovernmental agreement, mainly of a political nature, that will provide the legal framework facilitating eventual construction and operation of the EastMed gas pipeline. However, implementation of the project requires investors prepared to invest in the project and buyers of the gas in Europe. Neither of these is in place. This is an expensive project estimated to cost about $7 billion, but most experts consider this to be optimistic, expecting it to be closer to $8-10 billion. With the cost of gas in Israel, before it enters the pipeline, greater than $4.50/million b.t.u. (British Thermal Unit), the price of gas in Europe needs to exceed $8/million b.t.u. before the pipeline becomes commercially viable. In addition, the EU will publish by March 2020 the European Green Deal pushing towards cleaner energy, away from fossil fuels and with more ambitious climate goals by 2030 which, will make new gas projects more challenging.

Political Support for the EastMed pipeline but still an uphill…

For Israel, the U.S. and Cyprus, as well as Greece, the EastMed does not represent a simple gas supply pipeline, but a comprehensive strategic plan involving capital and other means, as well as the creation of security conditions in the region. The strong ties between Athens, Jerusalem, and Nicosia go well beyond the promotion of open communication links in the field of energy. The geopolitical/security perspective is crucial, but at the end of the day it is up to the market to define which project is preferable based on its needs.

This does not mean that the interests of states and companies converge in all cases. In the case of Egypt, for example, it seems to be against the East Med pipeline, but the creation of mechanisms such as the “East Med Gas Forum” shows each party’s level of dedication, including that of major stakeholders like the US, France, and Italy when it comes to reaching a point of mutually acceptable and beneficial agreements.

The East Med energy corridor, after all, includes the EastMed gas pipeline but also potential LNG exports from the region to Europe. Eventually, it may also include exports from Greece, should hydrocarbon discoveries be made. LNG from Egypt’s existing liquefaction plant at Idku is already been exported to Europe based on existing contracts, and exports from the second at Damietta may follow later in 2020.

At the end of the day, whether the EastMed pipeline materialises will not be decided by pure economics, but alongside the politics of this ancient region. And it may take a long time to pay back, pipelines however do have a habit of having a twist at the end of their tale.

The Geopolitical Environment

Last month Turkey signed an Accord with Libya’s internationally recognized government that seeks to create an Exclusive Economic Zone from Turkey’s southern Mediterranean shore to Libya’s northeast coast. Ankara says the deal aims to protect its rights under international law, and that it is open to signing similar deals with other states on the basis of “fair sharing” of resources. Τurkey has thrown a spanner into the works of efforts by Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Egypt to develop East Mediterranean gas, putting a barrier across the proposed EastMed pipeline. The $7-9 billion pipeline would have to cross the planned Turkey-Libya economic zone. Analysts say Turkey has effectively sent a message that it will not be ignored in the East Mediterranean, isn’t going to let EU members access what it sees as its maritime waters, and doesn’t want energy exporters like Egypt and Israel gaining leverage over Turkey, a net energy importer and transit state.

Egypt and Israel, that have invested heavily in energy exploration in the region, are alarmed by the Turkey-Libya move, which may threaten their ability to export gas to Europe. Egypt has called it “illegal and not binding”, while Israel has said it could “jeopardize peace and stability in the area”. Greece and Cyprus, which have long maritime and territorial disputes with Turkey, say the Accord is void and violates the international law of the sea. They see it as a cynical resource-grab designed to scupper the development of East Mediterranean gas and destabilize rivals. President Erdogan answered he would go ahead to have energy ships start drilling for oil and gas off Crete, with Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis warning the Turkish leader provocations in the Aegean and East Mediterranean won’t go unanswered.

Turkey’s organized plan, presented by the Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) to the Turkish government, was drafted in cooperation with the ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense. It foresees an intensification of the Turkish navy’s presence throughout the Eastern Mediterranean basin. It also stipulates continuous exploratory and drilling activities within the EEZ of Cyprus, while also calling for pressure to be brought to bear on Qatar to withdraw state-owned Qatar Petroleum from the consortium with US company ExxonMobil, which is active in block 10 of Cyprus’ EEZ.

In response to Turkey’s moves, Athens has embarked on a wide-reaching diplomatic offensive. More specifically:

– technical talks begun in Rome today (30/12) on the possibility of demarcating an EEZ between Greece and Italy.

– on January 2, Greece, Cyprus and Israel will sign, in Athens, the agreement to build the EastMed pipeline.

– this will be followed by a trilateral meeting between Greece, Cyprus and Egypt in Cairo on January 4-5, with the support of France.

– on January 7, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis will hold crucial talks with US President Donald Trump at the White House.

– on the same date, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo will travel to Nicosia to reaffirm the robust U.S.-Republic of Cyprus relationship.

– on January 8 or 9 technical talks on EEZ demarcation are scheduled with Egypt.

– near the end of January the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis will meet with the French President Emmanuel Macron to discuss about regional developments.

– the next East Med Gas Forum (Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt, Italy, Palestinian Authority, US) will take place later in January.

What are the wider repercussions?

As well as putting Turkey on a collision course with Greece and Cyprus, it ratchets up tensions between Ankara and the EU, adding to ongoing disputes over migration policy and wider questions over Turkey’s role in NATO. It also raises the stakes with Egypt, which has been at odds with Turkey since the Egyptian military overthrew Islamist President Mohamed Mursi in 2013. Many of Mursi’s Muslim Brotherhood backers now make their home in Turkey. In Libya, Egypt is more closely aligned with Haftar, meaning Cairo and Ankara are on opposite sides over the maritime deal.

Israel will soon send some gas to Egypt to convert into Liquified Natural Gas for reexport, so relies less on Greece and Cyprus.

Russia is another piece in the puzzle. While it and Turkey are at odds over Syria, they coordinate on energy policy, and Moscow is keen for Turkey to transship energy. But the Turkey-Libya deal also puts them on opposite sides in Libya, where Russia leans towards Haftar.

What does the Accord mean for East Mediterranean gas?

The East Med basin is estimated to contain natural gas worth $700 billion, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. At one point it was regarded as a boon for the region, one that could deliver massive revenue, help forge a resolution to the Cyprus dispute and build closer ties between Israel and its neighbors.

The key, however, to unlocking the gas’s value is exports and there’s no easy way to do that. The proposed pipeline is costly and would run 3,000 meters deep in parts. The Turkey-Libya deal adds another obstacle to making it achievable. While there are precedents for pipelines crossing other countries’ Exclusive Economic Zones, Turkey won’t make it easy. What’s more, Ankara will use the deal to step up its claims to explore for energy in waters off Cyprus, where for months it has sent drilling ships, and in recent days flown exploration drones.

Analysts already had doubts about the viability of East Med gas because of the export difficulties and the price it would ultimately be delivered at, with Europe awash with cheaper gas from Russia and Qatar. The Turkey-Libya move only further complicates that difficult picture.

On the other hand, with Cyprus, Greece and Turkey members and signatories of Energy Charter, the pipeline cannot be stopped, if it ever came to implementation. Whoever, has EEZ rights over the seas between Cyprus and Crete can only make environmental objections and may request rerouting of the pipeline, but according to the Energy Charter Treaty cannot stop it. Turkey is making a big move to try to force negotiations on a number of issues, that may prove very hard to resolve.

Nine states (Israel, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Russia, Italy, France and USA), six of them the oldest NATO members, have major to very high stakes in the “Big Game” of South East Mediterranean’s region. The experience of recent years suggests that ensuring peace and stability in the region is first and foremost the responsibility of these regional powers. At the same time, the business interests at stake in the wider area are also significant. More specifically active in the field of Israel’s natural gas production are companies such as: American Noble Energy, Hellenic Energean, the Israeli Delek Group, Isramco Negev 2, Ratio Oil Exploration. The Italian ENI operates in the Egyptian EEZ -exploiting the Zohr gas field. In Cyprus’ EEZ, exploration is being carried out by Noble Energy – Delek Group and Shell joint ventures in Block 12, ΕΝΙ in Block 8, an ENI & Kogas joint venture in Blocks 2,3 and 9, ENI and TOTAL in Blocks 6, 7 and 11, as well as the consortium of ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum in Block.

The Security Challenges

The recent history of the Mediterranean has taught us that there are no unilateral, political or military, solutions to stabilise the region. Several ongoing issues threaten the exploration, production, and transit of energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially the security environment, territorial disputes, and the macroeconomic climate. Recent developments, together with the uncertain future of the wider area (Balkans, Middle East, North Africa), suggest the need for enhanced security. Ongoing territorial disputes between several Eastern Mediterranean countries, especially the Turkey-Greece-Cyprus disputes over their respective EEZs, could hinder exploration and development in the region, particularly in the offshore Levant Basin. Disputes over maritime boundaries jeopardize joint development of potential resources in the area and could limit cooperation over potential export options.

At the same time, the security requirements of the already existing or to be constructed Critical Energy Infrastructures (CEI) are highlighted. Offshore drilling rigs, either fixed or floating, underwater drill sites, underwater pipelines for connecting the rigs to the drill sites, pipelines transporting the gas produced from platforms to the coast, and finally the EastMed Pipeline and EuroAsia Interconnector, make up a very extensive energy infrastructure grid, extending across the South Eastern Mediterranean and reaching Crete, the Greek mainland and onwards to Italy and the rest of Europe.

Areas of Strategic Importance: Cyprus and Crete

When attempting to plan the defence and security of an enormous region such as the Southeast Mediterranean, where a complex grid of offshore/onshore energy infrastructures is already being developed and is expected to develop further, one cannot avoid focusing on the two major island-“aircraft carriers” that dominate the region’s routes: Cyprus and Crete. The strategic values of these two islands are obvious as, among others, the routes of the proposed EastMed and EuroAsia Interconnector will pass through their areas. The “Achilles Heel” for the EastMed pipeline is the vast expanse that lies between Cyprus and Crete, which pose a challenge for security along the length of the energy routes.

Cyprus: The easternmost defense bastion of Europe

The strategic importance of Cyprus for the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean regions had been recognized since antiquity. A very recent historical example is the presence of the two Sovereign British bases on the Island (Dhekelia, Akrotiri). The first includes port facilities and the second an extensive air base. The preservation of these particular bases and of other facilities, such as the radar on the summit of Mt. Troodos, the highest peak in Cyprus, was defined as an inviolable term by Britain prior to its consensus in 1960, on the Proclamation of Independence for the state of Cyprus which until then had been British territory. More specifically, the southern and eastern coasts of today’s Republic of Cyprus, which are about 60% of the island, completely control the area between Cyprus, Egypt and Israel where the energy infrastructure and natural gas fields are currently located.

In the southern part of the island there is the “Andreas Papandreou” AFB at Paphos. The base was constructed in the 1990s as part of the implementation of the joint declaration of the “Single Greece – Cyprus Defence Area” doctrine. The base was constructed in order to accommodate Greek fighters staging in Cyprus. Today, it is used as the main base for the Cypriot National Guard’s Air Arm, where all its air assets are stationed (armed and attack helicopters, search and rescue helicopters, etc.). The base with its hardened aircraft shelters can accommodate the relocation of a reinforced aircraft squadron. Also, on the territory of the Republic of Cyprus is the Larnaca international airport with the capacity to serve large-sized commercial, as well as military, aircrafts.

To the east, near the city of Limassol, is the “Evangelos Florakis” naval base, which at the moment can only accommodate small sized vessels. That is why Cyprus, within the framework of the European Union PESCO (Permanent Structure Cooperation) initiative, shall upgrade and expand the naval base and shall also modernize the air base and the Zenon operation centre in Larnaca. France recently signed an agreement with the Republic Of Cyprus to co-fund the building of a new docking area at Mari, to allow larger French Navy’s warships to dock and service. Work has already started to upgrade the naval base. Cyprus will be an intermediary station for the French navy, following the loss of the bases France held in Lebanon and Syria, and especially for the Task Force formed around the “Charles de Gaulle” aircraft carrier, patrolling the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Republic of Cyprus has also two major commercial ports in the cities of Limassol and Larnaca, with the one in Limassol being the main port of trade for Cyprus and also an international transit trade hub.

The question is whether Cyprus is adequately defended, as it possesses no combat aircraft nor any major naval units. Nevertheless, Cyprus exploits its strategic position through the installation of anti-aircraft and anti-ship systems. In terms of anti-aircraft systems, the Cyprus National Guard has 6 self-propelled BUK M1-2 type air defence systems of Russian origin, 6 self-propelled TOR M1 short-range air defence systems also of Russian origin and finally 12 Skyguard a/a systems, which each of these consists of the FDC (Fire Direction Centre), 2 quad ASPIDE-330 rocket launchers and 2 twin GDF-0052 35 mm guns.

For strikes against enemy naval units, Cyprus has since the mid 1990’s acquired 3 EXOCET MM40 Block II surface to surface coastal batteries, with a maximum range of 70 km. Each battery consists of a self-propelled Command and Control Centre linked to a Score surface radar unit, the launcher unit consisting of a quad MM40 Block II missile launcher mounted on a Renault TRM 10.000 6X6 vehicle, plus an additional self-propelled NS-9003/A passive acquisition unit made by Israeli ELISRA. The passive acquisition units, acquired around 2000, have been mounted on STEYR 14M18 (5 ton) trucks and allow the location and acquisition of targets, with the minimum operating time of the Score radar to prevent its location by enemy countermeasures.

The US “Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act of 2019” seeks to lift the prohibition on arms sales to the Republic of Cyprus, establish a United States-Eastern Mediterranean Energy Centre to facilitate energy cooperation between the US, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus and authorise $2 million for International Military Education and Training (IMET) for Cyprus. So, Nicosia will be able in the near future to aquire high-tech weapon sustems, as well as the political alliance -even protection?- of the United States, over Turkey’s intransigense and growing aggressiveness.

According to US State Department, on January 7, the Secretary will travel to Nicosia where he will meet with President Anastasiades and Foreign Minister Christodoulides to reaffirm the robust U.S.-Republic of Cyprus relationship. While there, the Secretary will also meet with Turkish Cypriot Leader Akinci. The Secretary will reaffirm to leaders of both communities continued U.S. support for UN-facilitated Cypriot-led efforts to reunify Cyprus as a bizonal, bicommunal federation in line with UN Security Council Resolutions.

Joint military exercises

Of great interest is the fact that Egypt, Israel, Greece and Cyprus have been intensively involved in the Eastern Mediterranean during the last 8 years, mainly in bilateral exercises. The bilateral “MEDUSA” the largescale, for air and naval forces, exercises between Greece and Egypt began in December 2015, and the last “Medusa 9” was held in late November.

The exercise scenarios are gradually being expanded, and the participating forces are also increasing both in size and in the variety of the hardware involved.

Over the years, Cypriot and Israeli forces too have been participating in a series of large scale bilateral exercises (“Onisilos – Gideon”, “Nikokles – David”, “Jason”).

Commenting on the above exercises, one may note that they go beyond the usual level of combined exercises to exchange experiences and strengthen bilateral relations. Their scenarios are extremely complex with a very large number of participating forces and hardware, indicating that all four countries are intensely promoting their military cooperation to a

great extent and very frequently, to prepare for combined military action if necessary, but also to send convincing messages to anyone who might attempt to prevent this kind of co-operation, which includes cooperation-consensus on the exploitation of the energy resources in the Southeastern Mediterranean.

Last but not least, another particularly strategic parameter for Cyprus is the fact that, owing to its insular nature and its distance from both the Asian and African coasts, the island has a disproportionately large EEZ and FIR in relation to its land area. Cyprus’ really large EEZ is due to the provisions of the new 1982 Law of the Sea convention. The very large Nicosia FIR is one of the benefits of the British legacy, as its limits were defined at a time (1947) when Cyprus was still British territory.

States such as Israel with a very small airspace and a limited FIR, need a much larger airspace for their Air Forces to practice in, which requires application and approval by the air traffic management authority of the state controlling the neighbouring FIR. Today of course this is possible due to the excellent Israel-Cyprus relations.

The Fortress Crete

The strategic importance of Crete for the central and the eastern Mediterranean region had also been recognized since antiquity. During the Second World War, it was strongly fought over by the Germans and the British, and was eventually captured by the Germans after they conducted the greatest and bloodiest airborne operation until that time.

Nowadays, Crete hosts the Souda Bay Naval and Air Bases where U.S.A. and, generally, NATO forces are accommodated. Souda Bay is the second in importance naval base for the Greek fleet after its main Skaramangas naval base on the island of Salamina, adjacent to the port of Piraeus. The Souda port facilities are huge with the larger installation being Quay K-14 constructed with NATO funds. Its length, about 300 m, and width, about 100 m, allow an aircraft carrier to berth and it is the only NATO naval base to provide such facilities in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The U.S. Defense Budget for 2019 includes 2 sums of $47,850,000 and $2,220,000 for future infrastructures at the U.S. Suda Bay Base. These sums are a big investment and obviously show its high importance to the U.S. and NATO, as well as their will to extent their presence. Last October’s signing of the US-Greek updated Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement (MDCA) by the Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in Athens, together with the upgrade of the Strategic Dialogue between the two countries, will enable these investments.

The Air Base of Akrotiri, Chania, which serves the Souda base is home to the Hellenic Air Force’s 115th Combat Wing with two squadrons of F-16 Block 52+ fighters. These aircrafts were obtained from the outset with external conformal fuel tanks, in order to be capable of long range operations and can carry out missions reaching Cyprus. The Akrotiri AFB is itself part of the broader Souda infrastructure complex, serving thousands of flights per year by American and NATO transports, fighters and every other type of aircraft. It has been used extensively in all operations in the Gulf region (Desert Strom – Desert Shield in 1991, Iraqi Freedom in 2003 etc) and it was the base for NATO and Allied fighter jet sorties in 2011 against the supporters of the dictator Gaddafi in Libya. The significance of the Air Base is bolstered by the fact that U.S. monitoring operations are being executed at large, gathering imagery intelligence (IMINT), telemetry intelligence (TELINT), and signals intelligence (SIGINT) (for more see “ENERGY WARS: The Security of Energy Routes in the South East Mediterranean”).

Finally, the island also has several civilian and military airports, such as Heraklion International Airport, Sitia Airport and the airfields at Tymbaki (southwest of Heraklion on the South Mediterranean coast) and Kastelli (south-east of the city of Heraklion). At the latter location, the construction of the new international airport of Crete has begun to replace the one at Heraklion which is already congested.

Greece gives great importance to the security of Crete. As already mentioned a complete combat wing is stationed on the island, equipped with F-16 Block 52+ fighters and there are always Hellenic naval vessels at port at Souda. Additionally, the island is home to an airborne brigade, and particular attention has been given to its anti-aircraft protection. Crete is home to a long range air defence squadron equipped with the S-300 missile system of Russian origin, whose anti-aircraft umbrella is complemented by 6 self-propelled TOR M1 systems, also of Russian origin. Finally, located in Eastern Crete, on Mt. Ziros, is a major Air Force radar installation which is one of three area control centres in the Greek territory with a range of more than 450 km.

The Major Security Questions

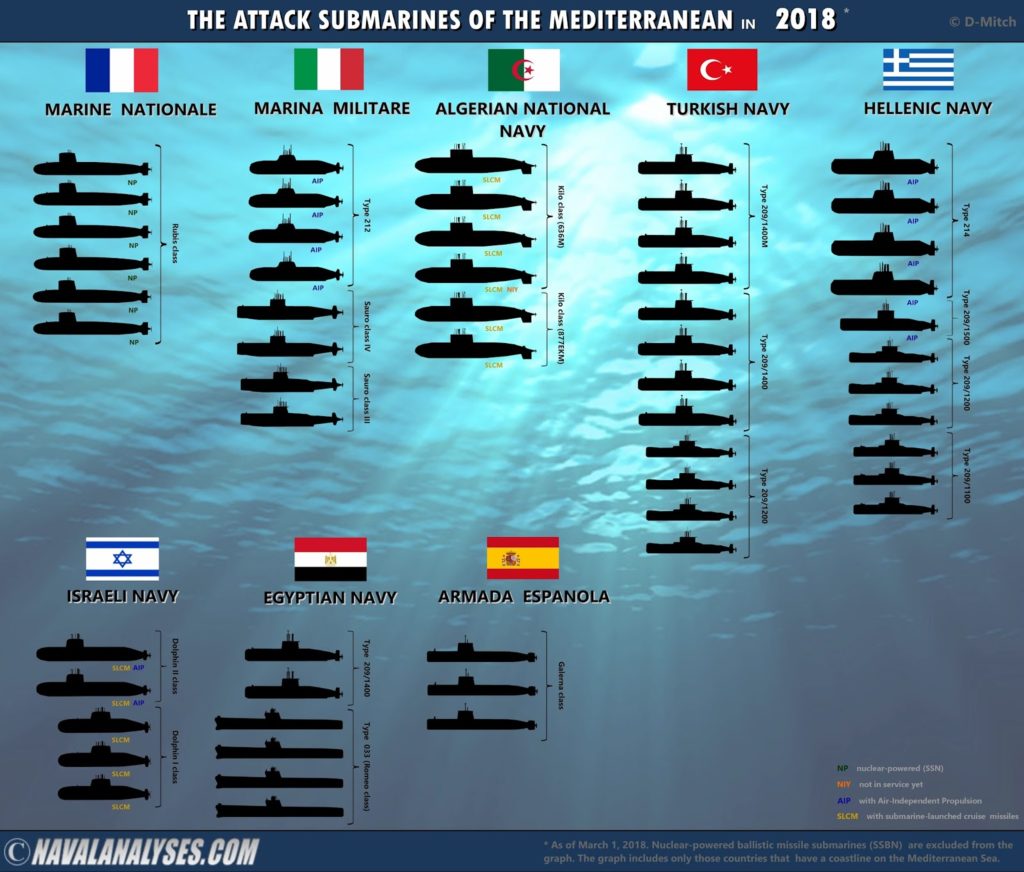

Military might and military means have become more important for littoral states and stakeholders regarding several critical issues ranging from energy competition to political signaling. Thus, the Eastern Mediterranean is witnessing more ambitious defense modernization programs and a significant increase in game-changing naval developments. Over the past decade, and while gas fields were consecutively being discovered, the countries of the region, as well as the major stakeholders, were entering into a peculiar sort of arms race. This was no coincidence. Valuable national resources discovered at sea require naval and air forces for their safeguarding.

All stakeholder states seem to be able to safeguard the part of their EEZ, where the energy resources are located and where their own production infrastructure is being developed. However, a major security issue arises concerning the vast sea area between Cyprus, the Dodecanese and Crete. Through this area will pass the routes of the proposed EastMed and EuroAsia Interconnector pipelines and in conclusion it shall be the area via which the energy transfusion to Europe shall take place. Therefore, significant security issues arise primarily during the preparatory-planning phase as well as during the future pipeline construction phase. Pipelines at such depths, once laid, are relatively safe of asymmetric threats, as there is no such international precedent, but such a possibility should not be ruled out. Surveillance and providing security over such a large maritime area requires:

- Constant aerial surveillance: Navy co-operation and surveillance aircraft, such as Greece’s P-3Bs which are being upgraded, designed to cover large distances, are a good but extremely expensive solution. Constant surveillance using long-range UAVs may be a solution with a reasonable cost. Today, available UAVs such as the Israeli Heron and Hermes 900, the American highly sophisticated MQ-9 Reaper/Predator B as well. UAVs can remain over an area being monitored for over 24 hours.

- Local presence or readiness of naval units of appropriate size for patrols on the high seas even in adverse weather conditions, but also capable of dealing with a variety of different types of threats. The most suitable ships are considered to be the size of a frigate or larger, having extensive air-defence capabilities.

Looking at the fleets of the regional stakeholders (Italy, Egypt, Israel, Greece, Cyprus and U.S.A.), it is easy to see that only the Italian, French and U.S. navies have ships that meet all these requirements. For any other naval unit to sail in the Eastern Mediterranean in relative safety from aerial threats, it should be accompanied by fighter jets, which practically means conducting a joint and prolonged aeronautical operation. This could potentially be implemented by having fighter aircraft in a state of high-readiness at a nearby air base (e.g. “Andreas Papandreou” in Cyprus) while at the same time adequately monitoring both land and airspace.

In times of tension or crisis, things would become even more difficult. In this case the continuous presence of an aircraft carrier that ensures the immediate availability of fighter aircraft is the greatest deterrent. Here, too, the US, French and Italian navies are the only ones with this capability. The effort to protect naval forces and energy infrastructure with fighter aircraft requires the mobilization of a very large number of aircrafts to ensure their continued presence while at the same time having available aerial refuelling and AEW&C aircraft. U.S.A., France, Italy, the U.K., Israel and Egypt as well as Greece (with restrictions) have such equipment. Any prolonged tension or crisis, however, will exhaust the national capabilities relatively quickly. Therefore, the combined presence of equipment from countries with common interests which, obviously for this reason too, practice together extremely demanding and complex operational scenarios, would particularly facilitate their implementation. Finally, the mutual provision of the facilities for stationing – servicing combat aircraft in other countries’ air bases would greatly diminish this problem.

The inclusion in the fleets of the region’s countries of Air Independent Propulsion submarines complicates the problem further. These submarines can remain on patrol for many days without having to surface, forcing their potential rival to conduct particularly complex anti-submarine operations, in order to counter this particular threat. Naval co-operation aircraft with increased detection and anti-submarine capabilities, the availability of naval units capable of transporting two instead of one anti-submarine helicopters, as well as the increased anti-submarine capabilities of surface vessels, will “make the difference”.

(for more read: Report#3 “Energy Wars: The security of the energy routes in the South East Mediterranean”)