Turkey’s insecurity and provocative actions may prove the fuse for a major conflagration. How the rest stakeholders eye these developments and what their reactions may be…

Anastassios Tsiplacos - Managing Editor

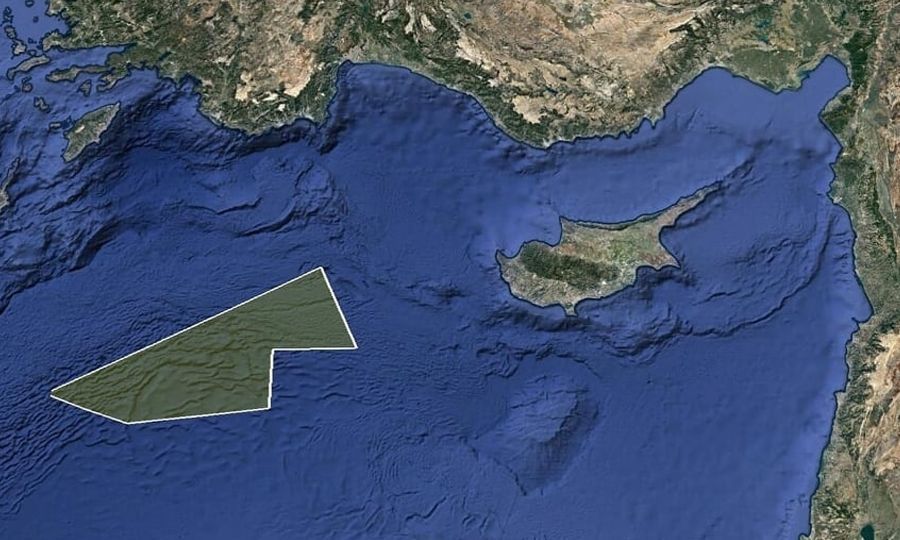

Greece has been placed on high alert in response to Turkey’s move to issue a Navtex reserving a large part of the Greek continental shelf south of the island of Kastellorizo for seismic surveys by the Oruc Reis research vessel until August 2.

Turkey’s plan is seen in Athens as a dangerous escalation in the Eastern Mediterranean, prompting Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis to state that“Greece is following all developments with absolute readiness,” stressing that “questioning the sovereign rights of Greece and Cyprus is questioning the sovereign rights of Europe,” warning that European Union sanctions could follow if Ankara continues to challenge Greek sovereignty.

The Greco-Turkish face-off

Turkey has boots on the ground in Syria, Iraq and Libya. Its navy is flexing its muscles in the Mediterranean. The next flashpoint could be not far from Turkey’s borders as Ankara is embroiled in a dangerous faceoff with Greece and where the drums of war are beating more and more loudly.

Under the “Mavi Vatan” or “Blue Homeland” grand strategy, Turkey’s increased investments in the naval capabilities are a deliberate effort to expand its reach into the Aegean.

Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said recently Turkey would start seismic research and drilling operations for natural resources in the part of the Eastern Mediterranean covered by the November agreement with the GNA. He added that Turkey was open to sharing with companies from third countries such Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States and Russia.

For its part, Greece has long argued that all of the 3,000 islands along Turkey’s western coastline -even those that are a few kilometres from Turkey’s shore- define the boundaries of Greece’s territorial waters and national airspace. This debate subsided when Turkey’s began the EU accession process a decade ago, but it is once again at the forefront of Greek foreign policy.

Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias answered that if Greece comes under armed attack from its Turkish neighbour, it will invoke a section of the 2009 Treaty on European Union that obliges member states to provide aid and assistance to another EU country facing armed aggression.

Greece also seeks to leverage EU opposition to the Turkish presence in Cypriot territorial waters to bolster its claims against Turkey in the Aegean. For now, Greece wants its European Union partners to prepare “crippling” economic sanctions for use against Turkey if it goes ahead with its planned offshore gas and oil exploration off Greek islands. “The European Union is Turkey’s biggest trading partner. If it wants, it can create a huge problem for the Turkish economy. That’s not my wish … but we must be clear.” Dendias has said.

KASTELORIZO: The “key” to the East Med for Greece and Turkey

Among the Turkish claims in the Eastern Mediterranean is the contentious and tiny island Kastellorizo and its smaller satellites, Ro and Stroggeli. These were granted to the Mussolini’s Italy through a series of agreements with Turkey and secured by Greece through the 1947 Treaty of Paris, a treaty that Turkey did not participate in, and thus, has never recognized Greece’s claims upon the island. The island is lightly defended by a small army base and an airstrip, and it has a population of fewer than 500 people. Still, its isolated location, far away from the major Greek islands, makes it a critical strategic location for Turkey to support its desired ambitions in the Mediterranean.

Greece is claiming an EEZ in the region of Kastrellorizo that is four times its square meter area. Still, Turkey has ardently argued against this, pointing to the Turkish precedent against international accords, which state that islands cannot create EEZ’s. Weeks after the Turkey-GNA agreement, Turkish Foreign Ministry affirmed this view.

Recent statements by US Ambassador to Greece, Geoffrey Pyatt, support the notion that Greek islands have rights to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf. If Greece were to act upon these claims, Greece’s held small island of Kastellorzio cuts Turkey’s EEZ claims in half. But what if Turkey enforces its claimed maritime boundaries? How would Greece, neighboring states, and the US respond?

Greece and Turkey have come to the brink of war 3 times since 1974

With Turkey’s behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean becoming increasingly provocative, Greece is bracing for a possible scaling up of tensions, possibly even during the summer, amid fears that Turkish officials will make good on threats to launch hydrocarbon explorations off the Greek islands of Crete or Kastellorizo, in the fringe of Greece’s territorial waters. Athens is weighing its diplomatic options while trying to keep channels of communication with Ankara, open despite the contrary stance of the Turkish government.

There are fears that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan might up the ante before with an intervention in the East Med in a bid to prevent an agreement on the delineation of an EEZ between Greece and Egypt, which is currently being discussed between officials of the two countries.

Officials in Athens are worried by the fresh areas of tension that Turkey has opened up, in a quite an aggressive fashion, across both the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean regions. In fact, they anticipate an escalation of tension off Cyprus’ coast, as well as the South Aegean islands and Crete.

As the situation unfolds, for Greece the war in Libya is gaining crucial national importance. From the developments there, the dynamics of the confrontation on the Greek-Turkish front will be affected to a great extent. If Erdogan wins in Libya, he will not only encircle Greece, but will also move from an advantageous position to the actual seizure of the Greek continental shelf-EEZ and beyond.

It is clear that in this eventuality the Libya-Turkey MoU, that delimits a rather paradox EEZ between them, will become entrenched, even if Greece declares that it is illegal and does not produce legitimate results. It is illegal by international Law and especially UNCLOS, however for Greece -and Egypt as well- it may produce real results.

On the other hand, if Erdogan flops in Libya, it is uncertain -if not the contrary- that he will be forced to fold on the Greek-Turkish front as well. To make matters worse, Turkey is once again threatening to open its borders for thousands of migrants wanting to cross into Greece and Europe, as it did in early March.

The Merkel trap, Erdogan the cat, Mitsotakis the mouse?

Time and again high-ranking Turkish government officials, commenting on the moves of the Turkish side and the reactions of the Greek side, have stated bluntly that President Erdogan is playing the cat-and-mouse game with Prime Minister Mitsotakis. But beware, he does not want to eat him, but to trap him.

Last year’s Erdogan-Mitsotakis meetings, primarily in New York and secondarily in London, proved rather disastrous for the later Greek-Turkish relations, with the responsibility mainly weighting the Greek mission, which went almost unprepared not so much in the agenda of the talks but in the way they “read” mr. Erdogan.

It is no coincidence that after the meeting of the leaders of Greece and Turkey in September in New York, the two Turko-Libyan Memoranda were signed, while after the meeting in London there was an attempt of refugees and immigrants to enter Greece from Evros, late March, and finally after the telephone communication between the two leaders, the Presidential Decree was signed to change the character of Hagia Sophia from a museum to a mosque.

On the other hand, in the effort of the Greek government to make “friends” the “enemies” of its “enemy”, rather reduced the contacts and relations that had been established in the previous period both in the region of the Balkans and in the South of Europe. The relations with the Balkans and the depreciation of the 7-part cooperation of the Mediterranean countries of the EU (Med7), have already brought negative results for Greece. At the last EU Foreign Affairs Council, among the countries that reacted to the imposition of sanctions on Turkey were Bulgaria, Romania, Italy, Malta and Spain. If nothing else it is a diplomatic failure for Greece, not to be able to convince its partners of its “right”.

In this context came the German Presidency from July 1, to make things even more difficult. Germany, as well as the EU leadership, consider Turkey an important partner. This has become clear at all levels, from all sides, so the Greek government should not rest on the repeated identical statements condemning Turkey verbally. Josep Borrell was clear; the EU wants a de-escalation of tension in the Eastern Mediterranean and a bilateral dialogue between Greece and Turkey.

Greece’s one-dimensional policy for economy and investments is a bargaining weakness. Everyone, especially Germany, knows its “Achilles heel” and on this weakness it is expected to base its policy on Greek-Turkish mediation, trapping Greece which will need financial support for the great recession that is coming due to coronavirus.

On the occasion of its six-month EU Presidency, Germany wants to end with the thorn of the Greek-Turkish dispute. This was clear from the participation of the German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas in the meeting of Borrell, Dendias, Christodoulides in Brussels, but also from the “unexpected” meeting in Berlin of the Director of the Diplomatic Office of the Greek Prime Minister, Eleni Sourani with Merkel’s advisor on Foreign policy Jans Hecker and Erdogan’s close adviser, Ibrahim Kalin.

The fact that Mehmet Cavusoglu, hastened to divulge the “secret” meeting, highlights that Turkey had reasons to exploit the event. These reasons are evident. When Turkey is subjected to global pressure over its decision to convert the Hagia Sophia into a mosque, the fact that it is “talking” with Greece, the country which has the most historical ties with the monument, is a reason to dull the pressure it is under. And this is an argument which Ankara is adopting to avoid any sanctions from the EU.

In any event, it is a mainstay of Turkish diplomacy when it creates a fait accompli to immediately call for dialogue to create a climate of acceptance for its actions.

This was a mistake on the part of Athens, made in its angst to deter the looming crisis, after Ankara’s announcement that it will conduct research just off Greek territorial waters in the Kastellorizo – Rhodes – Crete arc.

The Greek side has said in various tones that it will react if its national sovereign rights are violated. However, this message was never as clear as it should have been. As a result, decision makers in Ankara formed a different view, believing that Greece will not react, and that if it attempts in some way to hinder Turkish research, a limited hot incident will take place, which will force Greece to back down.

This is the prevalent view in Ankara. This is not a haphazard conclusion. It has been formulated through the wrong messages sent by Athens recently.

Nevertheless, this time the message conveyed by mrs. Sourani, responsible for the Greek PM’s diplomatic office, according to information that cannot be disputed, is that Greece is resolute in responding, even with the use of its armed forces, in order to defend its sovereign rights. What is equally important is that her Turkish interlocutor said that in Ankara it is believed that Greece is not going to react in such a manner.

Time for an anti-Turkish Mediterranean alliance?

At the point where things have reached, it is vital for Greece to abandon two traditional syndromes definitively and not just for the time being: First, military entrenchment within the Aegean. Secondly, understanding its foreign policy exclusively and unilaterally in EU terms. The European dimension is a given, but the events themselves have forced Greece in recent years to perceive itself as a Mediterranean power. The game in the Eastern Mediterranean, however, is played on other terms. It is not limited to the classic post-war diplomacy of cautious steps, if not inaction.

Greece obviously cannot shrink away from all that. It needs to protect its own vital interests and at the same time project its influence in the wider region. Turkey is already doing that and it is promoting its status at every chance possible. Furthermore, Ankara has developed quite a degree of self-confidence in terms of its naval prowess.

Greece is also obliged to defend Cyprus from any attack by Turkey, as formalised in the 1993 Greece-Cyprus joint proclamation of Single Area Defence Doctrine and beyond.

Greek governments have sought to increase the country’s leverage by launching cooperation schemes with Cyprus, Egypt and Israel. Greece hosts the annual “Iniochos” multilateral air force exercise, in which fellow NATO member Italy has twice participated in sophisticated military drills with Cyprus, Israel, and the UAE. It pariticipates also to the Egypt-Greece-Cyprus annual aeronaval exercise “Medusa”. These exercises build on the Greece-Cyprus-Egypt and Greece-Cyprus-Israel trilateral military relationships.

Such initiatives have intensified in recent years. However, they cannot solve the actual problem. This is an urgent matter. Solutions do exist and they have to be examined with the maximum possible degree of political consensus.

This practically means that the most effective way for Greece to defend its sovereign rights and at the same time to avoid war -or even a hot incident- with Turkey is to take theinitiative to form a military Mediterranean Alliance together with France, Egypt and Israel, with a distinct anti-Turkish tinge. It is not an initiative with a given successful outcome, however the conditions today are more mature than ever and it is definitely worth the effort.

The Hellenic Navy and Air Force

The Hellenic Armed Forces (HAF) face an increasingly complex operational environment. Athens sits in an increasingly hostile region with replete with irredentist neighbors, such as Turkey, and growing interest from the great powers, particularly from China and Russia. Despite common NATO membership, relations between Turkey and Greece have ebbed and flowed throughout the past 40 years, intensifying recently over Cyprus, Aegean Sea, and Eastern Mediterranean. The transatlantic security partnership is buckling, under the weight of political nativism and the competing national interests of its member states.

Greece is traditionally a major naval power. Anyone who has studied the country’s history can easily grasp that fact. No further explanation should be necessary. Many renowned analysts have pointed out that Greece would run into trouble every time financial stress took a toll on naval spending. The Hellenic Navy has found itself lagging behind due to the financial crisis. Sure, it can still fulfill its mission, but it is in urgent need of a brave modernization program. The details are known to those who ought to and who want to know. And at a time of open source information, these details are obviously not a state secret.

The “axis” strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean, led the Greek state to year after year dispose over 2% of its GDP in military expenditures for NATO, becoming the steadiest buyer of weapons in the euroatlantic alliance. Despite the economic crisis, Greece seeks to modernize its naval and air forces, aiming to retain the technological military advantage. Lately, the Navy’s modernization programe has been in the middle of an armament antagonism between France and U.S.A., two of the oldest allies and arms suppliers of Greece.

The main Greek naval units are: 4 “Hydra” class type MEKO 200HN frigates, of German origin, which entered service from 1992 to 1998, 6 KORTENAER “S” frigates of Dutch origin, modernized in the years 2007-2010, 3 KORTENAER “S” frigates that have not been not modernized, 11 submarines and 17 missile boats (5 British SUPER VITA, 4 modernized French Combattante III, 5 also French Combattante IIIB and 3 former German S148). Deliveries over the past decade have includes 5 AIP submarines: 4 “PAPANIKOLIS” class type 214 and a completely upgraded type 209/AIP and 2 “ROUSSEN” class, Super Vita type missile boats. Another two Super Vita boats are being built in Greece, but the program has suffered very long delays.

The Hellenic Air Force’s major fighter aircrafts belong to 3 main types: F-16, Mirage 2000/2000-5 and F-4. Deliveries over of the past decade have been 30 F-16 Block 52 + Advanced during 2009 – 2010. Very recently, it was decided to modernize 85 F-16 (55 Block 52+ and 30 Block 52+ Advanced) to F-16V (AESA radar) standard. In addition, the country is modernizing 5 P-3B naval co-operation aircraft. The Hellenic Air Force also uses 17 Mirage 2000B/EGM-3 (delivered 1988 – 1992), 24 Mirage 2000-5Mk 2 (delivered 2007 – 2009), 32 F-16C/D Block 30 (delivered 1989 – 1990), 39 F-16 C/D Block 50 (delivered 1988 – 1992), and 34 F-4E upgraded to Peace Icarus 2000 standard, during 2003-2004. Finally, the Hellenic Air Force also has four Erieye EMB-145H (delivered in 2008) AEW&C aircraft.

After the exclusion of Turkey from the F-35 project the Greek government, seeking to exploit the air power void in the region, has already submitted a “Memorandum of Interest” to buy over-expensive state-of-art American F-35 airplanes.