The Russian Air Defense System is only the tip of the iceberg, albeit a sharp one, in the US-Turkish relations

Turkey is stretching its arms in the Eastern Mediterranean, North Africa, Middle East, and the Caucasus. The latest reports on Turkey have presented a gloomy picture of Ankara’s relations with its western allies amid a string of developments that are alienating it. Turkey’s new security doctrine suggests that since foreign policy makers in Ankara understood that the country’s claim to soft power in the Middle East was gone, it was time to adopt a different approach and exert hard power in the region.

South East Med Energy & Defense reported last October: “…If NATO-member Turkey has tested its Russian-made S-400 Triumph advanced air defense missile system, then it is raising the specter of a new standoff with the United States. These S-400 tests appear to be another example of a broader strategy of asserting Turkey’s independent foreign policy aspirations and increasing its geopolitical influence from the Black Sea through to the eastern Mediterranean, one that has already caused significant frictions with its traditional allies.” (see: “S-400: President Erdogan’s “Achilles Heel”?).

Anastassios Tsiplacos - Managing Editor

Several arguments prove Turkey is a real challenge for Biden’s foreign policy. Its adversarial approach in foreign relations is very likely to eventualy lead to a shift in the United States’ Turkey policy, from cooperation toward containment. The most immediate decision that could be addressed by the White House could involve the sanctions that were levied in December 2019 for the S-400s. Secretary of State Antony Blinken openly spoke about this when he referred to Turkey as a “so-called strategic ally” in his confirmation hearing in January.

In recent days, the S-400 issue, which has become a neverending narrative in Turkish-American relations, entered a new era with statements from both sides. US Deputy Secretary of State, Wendy Sherman, held a meeting with Turkey’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sedat Onal when visited Ankara, in order to nudge the Turkish government into action on the issue of S-400s.

“We have offered alternatives to Turkey, they know exactly what to do if they want to get out from underneath these sanctions. We have talked about ways to take the necessary steps. And this will be a decision for Turkey to take. I hope that we can find a way forward.” said in an interview with CNN Turk.

In response, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said that Russian experts would not remain in Turkey and that the S-400 will be under complete Turkish control. This statement was a signal that Turkey is interested in making some compromises with Washington. The foreign minister, however, added that though the Russian experts would be sent back to Russia, Turkey would not give up on the S-400s after an acquisition process that cost Ankara close to $2 billion in 2017. “It is not possible to accept calls from another country to “not use” them,” he said. Evenmore, under the terms of its agreement with Russia, Turkey is slated to acquire four battalions of S-400 batteries.

And then, some days before the Turkish President is about to meet with his U.S. counterpart, rumors started swirling of an impending deal on Russian S-400 missiles, that would help salvage relations between the NATO allies and see the equipment placed under US custody. The U.S. administration has asked Turkey for a written assurance that it will not activate the Russian S-400 missile defence systems, pro-government newspaper Hurriyet wrote. In this respect, Hurriyet continued, the administration of Joe Biden plans to submit the Turkish assurances to U.S. Congress to end the sanctions against Turkey, adding that U.S. military experts would be following up with Turkey on the matter.

The plan of the Turks, which was rejected by Washington, was to put as a last step its proposal for the transfer of the Russian system to Incirlik and this to be controlled by a joint committee of Turkish and American officers. The Turkish government presented its own proposal as American, dragging several media outlets that broadcast it as a fact.

Nevertheless, Greek website “Hellas Journal”, as well as another American journalist, submitted the following written question to the State Department: “According to Turkish media, the US government has changed its position on the Russian S-400 system. Turkish media insist that the US government has asked Turkey for written assurances that it will not activate the S-400. According to the Turks, the government of Joe Biden plans to submit the document to the US Congress to end the sanctions against Turkey. Have you changed your position on the S-400?”

The answer was stereotypical: “Our policy has not changed. “he United States have not singled that it would accept Turkey keeping the Russian-made S-400 defence system if it were under US custody” mr. Ned Price said. Asked whether the Biden administration has ever either floated or entertained the proposal of Turkey deploying the Russian S-400s at NATO’s Incirlik airbase, Ned Price responded: “We have never offered any indication that we are willing to accept Turkey’s possession of the S400 system. We urge Turkey to abandon the S-400 system. Turkey’s acquisition of the S-400 –and let’s be very clear about that– is in direct conflict with its NATO commitments, endangers the security of US and Allied military technology and personnel, and undermines NATO cohesion and interoperability.”

THE SANCTIONS

The Trump administration took the initiative last December to design and announce sanctions ahead of a looming Congressional deadline at that time, which as a result gave the Executive Branch more freedom to design the sanctions program.

Washington’s list of sanctions is less than a full arms embargo; readers will also recall Turkey had previously been ejected from the American F-35 fighter jet program. The focus of the US sanctions is a relatively narrow band of Turkey’s defense industrial structure, much of which remains highly dependent on US technology and requires US authorization for technology re-exports.

In legal terms, the sanctions applied to Turkey are considered secondary sanctions under CAATSA because the Turkish companies opted to conduct transactions with entities previously listed on the US List of Specified Persons (LSP). Under CAATSA, the LSP is the list of Russian entities that are considered “primary sanctions targets” due to previously identified Russian foreign policy decisions in Ukraine, cyberspace, and intrusion in the 2016 U.S. elections.

The State Department explained last December its rationale for the sanctions. “Today, the United States is imposing sanctions on the Republic of Turkey’s Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB) pursuant to Section 231 of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act for knowingly engaging in a significant transaction with Rosoboronexport, Russia’s main arms export entity, by procuring the S-400 surface-to-air missile system. The sanctions include a ban on all U.S. export licenses and authorizations to SSB and an asset freeze and visa restrictions on Dr. Ismail Demir, SSB’s president, and other SSB officers.”

Those other senior SSB officers include Faruk Yigit, SSB’s vice president; Serhat Gencoglu, SSB’s head of the Department of Air Defense and Space and Mustafa Alper Deniz, program manager for SSB’s Regional Air Defense Systems Directorate. (see: How hard CAATSA sanctions will hit Turkey?)

Why did Turkey buy the S-400 system?

As a NATO member, Turkey is a country that benefits from Alliance’s missile air defense system umbrella. One of the most important elements of this umbrella is the Kurecik radar base in Turkey. There are other elements of NATO’s missile system as well. In part, it has American ships in the Mediterranean, missiles stationed in Romania and Poland, AWACS aircraft and other pillars. In summary, there are many elements of the NATO’s missile defense system and Turkey, as a NATO member, benefits from the protections provided by this system. This should always be kept in mind.

Well then, “Why did Turkey buy the S-400?” comes the question. In addition to NATO’s missile defense system, Turkey wanted to have a defense system that it could include in its own national inventory. In other words, Ankara wanted an air and missile defense system with full control authority. Control of NATO’s missile defense system is not entirely in Turkey. In fact, there is no such thing as control, it has to be said. After these types of systems are established, they are not systems that work with human decision. Within this established architecture, the system automatically becomes operational in line with the real-time information received. As a result, Turkey wanted to buy a system that would be in its inventory and that it had the authority to push the button, in order to develop its own national capabilities apart from NATO’s missile defense system. This decision stemed from President Erdogan’s alleged suspicions that the 2016 coup was planned by FETO, Gulen’s organization, in conjuction with the U.S. The real problem arised from the fact that Turkey’s final choice is a system that is not compatible with NATO systems.

(see: S-400 Games: How much of a real threat are…)

In this respect, Turkish Defence Minister Hulusi Akar has said “Turkey has exercised its sovereignty rights by choosing the Russian-made S-400 missile defense systems”, as he noted that air defense systems have become a necessity for Turkey in the face of increasing risks and threats. He also rejected claims saying that Turkey preferred the S-400s over the Patriots even though the country had the chance to purchase the latter, as he explained that the U.S. has failed to positively respond to Turkey’s expectations. “We wanted to purchase the Patriots from the U.S. and the SAMP-T from France-Italy, but this was not possible due to various reasons,” Akar has said.

This statement was not correct because the Patriots were offered to Turkey twice before. Subsequently, Turkish government shifted from “they did not sell it to us” to “they did not provide technology”. The second explanation was correct. It should also be remembered that the S-400 systems do not involve technology transfer in any way. It is wrong to expect Russia to transfer technology to Turkey, which is a NATO country. Besides the S-400 and Patriot discussions, Turkey actually missed a more important opportunity for itself. Turkey was negotiating for the new version of the SAMP/T system within the scope of the Eurosam project planned as a European consortium. In the Eurosam project, a negotiation process including technology transfer on design and production was developing with the joint contributions of Turkish and European companies. While Turkey was negotiating with the European side, involving the technology transfer of the new version of SAMP/T systems, the S-400 decision eliminated this option.

“We will open negotiations for a model used for the S-300s in Crete…”

Turkey tried to open discussions for the “Crete model”, as they call it, regarding the use of the S-400 missile system. Defense Minister Hulusi Akar addressing reporters in the past, evaluated the tensions between Turkey and the United States over the advanced S-400 Russian air defense system saying “We will open negotiations for a model used for the S-300s in Crete,” referring to Greece’s use of the Russian S-300 missile system, despite being a NATO member.

The S-400 is an upgraded version of the S-300 air defense system, which is available in many countries, some of them NATO members. Many Soviet-era weapons belonging to Europe’s former Warsaw Pact countries were kept within the NATO system, when those countries joined the alliance. NATO member Bulgaria operates a multi layered Soviet air defence network, comprising S-300 and S-200 long range missile defence systems, complemented by S-125 and S-75 short and medium range ADS.

Back in 1996 Cyprus signed a deal with Russia for the purchase of S-300 PMU1s for deployment on Greek Cypriot soil. These missiles could not be deployed in the Republic of Cyprus, as a result of Turkish pressure, but in 1998 they were deployed in storage in the Greek island of Crete, whose strategic importance has been rising steadily.

Greece did not activate the systems until a military exercise in 2013. Furthermore, Athens signed new agreements with Russia in 1999 and 2004, to purchase TOR-M1s and Follow On Support (FOS) for its OSA-AKM (SA-8B) medium-and low-altitude air defense systems. These Russian-made air defense systems are currently an integrated part of the air defense system of Greece, while a number of TOR-M1s and BUK air defense systems have been deployed by the Greek Cypriot National Guard.

The Greek Armed Forces carried out the first test firing its S-300 at the NATO Missile Firing Installation (NAMFI) in Crete, as part of the “Lefkos Aetos 2013” (White Eagle 2013) military exercise. The firing of the systerm occurred some 14 years after its initial purchase. In 23-27 of November last year, Greek media reported that Greece fire tested again S-300s at NAMFI in Crete, together with Germany’s, Netherlands’ and U.S.’ TOR-M1, OSA-AKM, Hawk, ASRAD and the Stinger man-portable air-defense system (MANPAD).

In this respect, Turkey has proposed only partially activating its Russian S-400s in negotiations with the United States. “We don’t have to use them constantly,” Akar was quoted as telling Turkish reporters. “We have said these talks could be held under the umbrella of NATO. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg also said he viewed this issue positively,” he added. Indeed, NATO’s Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg reiterated last October that it was a national decision what kind of defense capabilities different allies acquire. “But at the same time, what matters for NATO is interoperability and the importance of integrating air and missile defense, and that cannot be the case with a Russian system S-400,” had added. However, Washington has opposed NATO’s Secretary General saying any talks between the two allies could take place under the NATO roof.

Turkey’s contradictive statements…

Following suit, Bloomberg News Ankara penned an article, where they said Turkey was “…prepared to make concessions“ because it was “…eager to secure the future supply of spare parts for its U.S.-made weapons systems and avoid damage to its economy,” citing Turkish officials familiar with Washington-Ankara relations.

Speaking in an interview with state broadcaster TRT Haber, presidential spokesman Ibrahim Kalin said that Akar’s comments had been misunderstood, as far as the so-called “Crete Formula”, adding that there is no such formula on Turkey’s agenda and underlined that Ankara’s S-400 policy has evolved over the years, not in a day. He also said talks were being held with Washington over disagreements, but that quick solutions to problems over a host of issues should not be expected.

Furthermore, Kalin blamed the United States for putting strain on Turkey, saying the country was inconsistent. The contract for the S-400s was signed “…approximately four months before the CAATSA sanctions”, the spokesman has told state-run TRT Haber. “From a legal point of view, what they say is inconsistent,” and concluded that Ankara will not turn back from its acquisition of Russian S-400 defense systems, however will seek to resolve issues with its NATO ally through dialogue.

On the other hand, Turkey has seen little consequence from U.S. sanctions over the purchase of the Russian-made S-400 missile system, TASS news agency has said. Τhe U.S. sanctions have had a limited impact the Russian news agency said, citing a televised interview of SSBs President Ismail Demir. “We have not noticed any direct effect (from U.S. sanctions). We will see the fallout from applying CAATSA but at present there are no clear consequences and we will wait,” Demir has told broadcaster NTV, according to TASS. On the contrary, Turkey was moving forward with purchasing more of the missiles, he said. “Our work on the second (regiment) of S-400 systems continues.”

“Crete model” unlikely to work for Turkey’s Russian S-400 missiles

On the other hand, the Biden Administration believes that the S-400 missiles create a bigger threat to NATO and the United States, than the S-300s, Pentagon spokesperson Thomas Campbell has said, adding that all offers for the sale of the U.S. Patriots have been rejected by Turkey. The S-400 system is far more advanced than the S-300 one, and there remain deep concerns, especially from the U.S., that even a passive S-400 deployment for training purposes could be used by the Russians to gain precious intelligence on western made fighter jets in general. This is a basic fact from the commercial leaflet, they are meant to down US made F-16s and F-35s.

Consequently, if Ankara is suggesting a “Crete model” that could satisfy Washington’s demands -and have U.S. sanctions under CAATSA imposed on it removed- it would need to be a model whereby the missiles are moved out of country. Storing the S-400s in Northern Cyprus might be such an option. That, incidentally, wasn’t the first time the idea of relocating the S-400s outside of Turkey was suggested. In June 2020, U.S. Senate Majority Whip John Thune proposed that Washington could buy the S-400s in order to have them verifiably removed from Turkey. Turkish state-run Daily Sabah newspaper questioned if deploying Turkish S-400s in Libya -where the Turkish military has a sizable presence, including air defences- would be acceptable for the U.S. and Russia.

Nevertheless, international analysts are highly sceptical about the relocation of Turkish S-400s to either Northern Cyprus or Libya. Northern Cyprus would be a very unlikely compromise, given that the U.S. does not recognize the country, and the move would alarm the Europeans Greece, and Cyprus would be alarmed by any S-400 deployment in North Cyprus since they would view it as “a weapons system that could be utilized to further entrench Turkey’s control of the north.” Furthermore, it would necessarily not fall under compliance for the U.S. NDAA (National Defence Authorization Act), which demands that Turkey no longer use the S-400, even in a foreign setting. To send it to Libya would also violate the UN arms embargo, something the U.S. would oppose.

Even more, there is no chance that Russia will accept storage of the S-400s -especially under US custody. Would the US let Turkey park Patriot missiles on a Russian base? No way. So why would the Russians accept that? The S-400s were more than an arms sale; they symbolized Russia’s effort to use Turkey to drive a wedge into the Western alliance. If Erdogan, in effect, gives up the S-400s, it’s a signal of failure -at least partial failure- of that effort. It is doubtful, also, that Moscow’s concern would be about compromise of its technology. Surely they didn’t have any illusions in transferring the S-400s to a NATO country that the US and its allies would find a way to examine the technology. For that reason, it’s a safe bet Turkey didn’t receive Russia’s most sophisticated version of the S-400s.

Speaking to Russian TV channel RT, Sergey Chemezov, CEO of the Russian Rostec Corporation, said that the S-400s are defense weapons and cannot be used in attacks. “Therefore, I cannot imagine how they can affect NATO countries’ security. On the contrary, the Turkish side ensures the security of NATO countries,” he stated.

In fact, by proposing the “Crete Model”, Turkey is trying to make a NATO argument to get to keep its S-400s and remain a candidate to receive the F-35. Nevertheless, it is almost certain that the U.S. will not alter its approach on the joint F-35 program in the short and medium-term.

Even more, State Department’s spokesman Price has said that U.S. policy opposing Turkey’s Russian S-400 missiles remains unchanged and will not lift sanctions. Asked whether the United States is considering Turkey’s recent suggestion that it may not need to make the Russian S-400 missile defense systems operational all the time, Price said Washington’s policy remained unchanged. The U.S. administration has so far based its arguments on this issue on the claims that it provides “income, access and population to Russia” and that “Russian S-400s are incompatible with NATO equipment, they threaten the security of NATO technology, and they’re inconsistent with Turkey’s commitments as a NATO ally.”

Turkey’s S-400 purchase as a sign of shifting strategic view on United States

Now all eyes are on the impending meeting of U.S. President Biden and Turkish President Erdogan, during which both leaders will debate over the Turkey’s purchase of Russian S-400 defence missiles which U.S. and NATO deems incompatible with its systems. The S-400 issue, however, is only the tip of the iceberg of the issues that have deteriorated the American-Turkish relations. While it is undoubtedly a big thorn in the U.S.-Turkey relationship, it is not the only issue on their agenda. There is a broader ongoing problem of trust, because there is a fundamental divergence of interests and goals. Whereas Ankara is attempting to strengthen its position in a new regional order, Washington seeks to preserve close cooperation with other countries in a new world order. In this sense, American relations with Turkey have come to resemble those with Pakistan to a degree –allies on paper, based on a narrow set of shared interests, but in practice too deeply distrustful of one another to meaningfully cooperate.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to say Turkey’s purchase of Russian-made S-400 missile defence systems stemmed from frustration with the United States only, as Ankara’s new strategy shows its changing mind about the United States. The issue has turned into, “Why are you making that deal with Russia?”, with Ibrahim Kalin giving the answer that “Russia is an important actor in our region. How we relate to it is important.”

Turkey is not only a critical country for the American interests in a wider region. It is a paradigm for Biden’s foreign policy. The upgrade of Russian-Turkish relations is a factor that, progressively, weakens the cohesion of NATO. The acquisition of the S-400s by Turkey means something more than a simple military transaction between the two states. It means a shift of Turkish foreign policy that no one could ignore in Washington, especially when Turkey, Russia, and Iran have important cooperation on Syria’s issue.

Turkey’s primary goals

Ankara’s primary aim is to end the existence of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and its extensions, which threaten its national security and territorial integrity. It is Turkey’s ultimate goal to eliminate the PKK and to ensure it is not used as a kingmaker against them. Turkey considers also the Syrian People’s Protection Units (YPG) to be a terrorist organisation over its alleged ties to the outlawed PKK, which is included in the United States’ list of foreign terrorist organisations as well. However, Washington has worked over the years to distance its Syrian Kurdish allies from the group.

Relations between Ankara and Washington will remain strained unless Washington cut off its support for the YPG. In recent statements Defense Minister Akar seemed to tie the S-400s issue to Washington’s support for the YPG in the fight against the Islamic State in Syria, saying the disagreement about the YPG could not be resolved without concession from Washington. While Washington maintains that YPG has no afiliation with the PKK, “One thing is certain: The YPG is receiving instructions from the PKK,” Akar has said. While the S-400 issue can be resolved in a joint working group, Akar stressed, the matter of the YPG couldn’t. “We will see if (the Biden administration) acts in prejudice. We expect empathy. We approach matters with reason, not emotion.”

Does U.S. use S-400s as leverage against Turkey for northern Syria plan?

If the S-400s is Washington’s main problem, American support for the Syrian Kurds is Ankara’s. Ibrahim Kalin has emphasized “Regarding the YPG, the U.S.’ insistence on its wrong policy, not only fails to solve the Syrian crisis but also damages our bilateral ties to a further level. Biden administration should reconsider this policy seriously.“

For Turkey the real goal of Washington behind creating an issue over the purchase of the S-400s seems clear. Ankara’s foreign policy makers tend to believe that the newly elected Biden administration and its Middle East advisers in the White House, are preparing to make a move in Syria and Iraq. Just as Turkey wants to end its Sinjar-based PKK presence in northern Iraq, in coordination with Irbil and Baghdad, Washington’s efforts to bring the ENKS and PKK together are intensifying.

United States’ Middle East Policy

As a candidate, Biden opposed former President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw U.S forces from Syria in October 2019. Members of his cabinet, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, have advocated for continued U.S support for the largely Syrian Kurdish forces in northeastern Syria, and he is joined by like minded officials like White House coordinator for the Middle East Brett McGurk. In fact, the Biden administration has not released any detailed U.S strategy for Syria since it was installed in January. Several outlets reported that the administration is looking to avoid prioritising the Middle East, as it pivots to other foreign policy challenges like relations with China and combatting climate change. Nevertheless, the United States has been cooperating with the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria against Islamic State (ISIS) and will continue to do so under President Joe Biden, Pentagon’s press secretary John Kirby has stated. He has said also that U.S. military efforts in Syria and Iraq were solely focused on countering the threat from ISIS.

The SDF is dominated by the People’s Protection Units (YPG) militia, which are, partialy, an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The latter has been fighting an armed insurgency for Kurdish political autonomy in Turkey since 1984 and has bases in northern Iraq that are being attacked by Turkey. It is recognised as a terrorist group by the United States and the European Union.

On the other hand, Turkey strongly opposed the YPG’s presence in northern Syria. Ankara has long objected to the U.S.’ support for the YPG, a group that poses a threat to Turkey. Ankara has strongly reiterated that under the pretext of fighting Daesh, the U.S. has provided military training and given truckloads of military support to the YPG, despite its NATO ally’s security concerns. Underlining that one cannot support one terrorist group to defeat another, Turkey conducted its own counterterrorism operations, over the course of which it has managed to remove a significant number of YPG fighters from the region.

US fortifies its positions in northern Syria

The Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) has reported that the US-led coalition is building a new base in northeastern Syria, citing local sources. According to the state-run agency, the base is being built 1km southeast of the village of Ain Diwar, in the al-Malikiyah area in the northeastern countryside of al-Hasakah. The area oversees Syria’s border with both Iraq and Turkey.

Local sources told SANA that reinforcements of the US-led coalition, including construction equipment, aim to establish the military base in the region, in addition to reinforcing American-occupation points and its bases in the vicinity of oil fields. SANA noted also that the US-led coalition built a new airstrip near al-Omar oil fields in the southeastern countryside of Deir Ezzor earlier this year. The recent developments indicate that the US is planning to increase its troops in northeastern Syria. US President Joe Biden voiced his support for long-term military presence in the region during his campaign.

According to local sources, there are U.S. efforts to unite the scattered Kurds in Syria, their political, military, economic and administrative integration, the sharing of Syrian oil and agricultural products of the region, coordinating and controlling the armed forces and bringing 6,000 Roj Peshmerga troops from Iraq to Syria. The Roj Peshmerga are trained by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)-affiliated Peshmerga special forces.

In this respect, the Commander-in-chief of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) Mazloum Kobani Abdi, has met with General Paul T. Calvert, commander of the U.S.-led Combined Joint Task Force (Coalition against ISIS), and Kenneth F. McKenzie, commander of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), pro-Kurdish Rudaw news site reported. Abdi announced the meeting on his social media account saying he was pleased to discuss both economic and security issues in the region with Calvert and McKenzie.

The US-led coalition has officially denied increasing the number of its troops or bases in Syria’s northeastern region. Last year, however, former US Special Representative for Syria James Jeffrey acknowledged that US officials lied to then president Donald Trump about the number of forces in Syria.

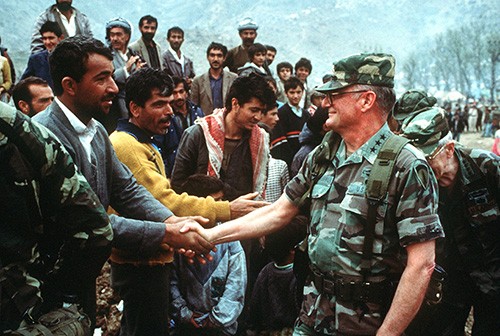

Biden administration: We have a “strategic partnership” with the Kurdistan Region

As a late development, testifying US intentions, two US officials -one from the White House and another from the Pentagon- made important statements in a webinar, hosted by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Representation in Washington, marking the 30th anniversary of Operation “Provide Comfort”, the US-led humanitarian operation that followed the ceasefire to the 1991 Gulf War. That operation brought some two million Kurds down from the mountainous borders with Turkey and Iran, after US President George H. W. Bush ended that war with Saddam Hussein in power and then tried to turn a blind eye to the humanitarian crisis that followed.

When the two Biden administration officials spoke, they each made clear they were speaking in the name of their bosses: Brett McGurk, National Security Council Coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa, in the name of President Joe Biden and Dana Stroul, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for the Middle East, in the name of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin. And they had the message: “we see our relationship with the Kurdistan Region -people and government- as a “strategic partnership.”“

Indeed, both officials read from written statements, reinforcing the point this was a message from the new US administration to the Kurdistan Region, government and people: we consider our partnership with you to be a strategic relationship that advances your interests, as well as ours. This partnership is not tactical, something temporary and subject to change, with the winds of erratic and passing circumstances. Instead, it is strategic; overarching and long-term, developed over the past three decades.

It all comes down to the fact that the KRG is a beachhead for the United States in the core Middle East. Erbil Airport has become a key node in the US security network in the region. The Iraqi Kurds have proven to be strong partners of the United States and especially reliable in what is becoming an increasingly hostile Iraq. Without the KRG, there would not have been a successful counter-ISIS mission, and the KRG is a core part of the US strategy to remain, even with a reduced posture, in the Middle East.

The stance of the Biden administration -“strategic partnership”- marks a significant evolution in US policy. No prior administration has articulated that so clearly. It has essentially said: we will not use you to confront the crisis de jour and then, once it has passed, throw you under the bus, as has happened before, most recently in 2017, when Washington turned a blind eye to Baghdad’s attack on the Kurdistan Region, in a military operation organized by Iran.

In parallel, a delegation from the US State Department travelled to northeast Syria, in the first visit to the region since President Joe Biden came to office in January. The trip was made by Acting Assistant Secretary Joey Hood, joined by Deputy Assistant Secretary and Acting Special Representative for Syria Aimee Cutrona and Deputy Envoy for Syria David Brownstein. White House’s National Security Council Director for Iraq and Syria Zehra Bell was also present on the visit to Syria.

According to the State Department, the officials met with members of the SDF and its political counterpart the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC). They also had meetings with leaders of the U.S-led coalition forces, local tribal leaders and humanitarian organisations operating in the region. The visit by the Biden officials took place after a separate meeting with Iraqi Kurdish leaders in Erbil, Iraq.

Turkey: “The Ally from Hell”?

On June 14, United States President Joe Biden and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will have their first face-to-face meeting on the sidelines of a NATO summit. For the 6-month inaugurated U.S. President Joe Biden and his administration, Turkey now presents not a relationship to be restored but an unsolvable foreign policy problem to be managed and mitigated as best as possible. The wider goal of Biden’s foreign policy is to send a global message -via Turkey- that if any state aspires to get US support, should fully comply with international law. Finally, the usage of democratic values as an instrument of US foreign policy.

The future of American-Turkish relations is still unclear, but for now, Turkey is between a rock and a hard place. Erdogan has to solve a tough dilemma. The Turkish presence in Nagorno Karabakh, Syria, and Libya depends on Russia, but the potential amelioration of the Turkish economy is connected with the West.

The economy that has underpinned Erdogan’s staying power, his Justice and Development Party (AKP) has governed alone since 2002, is in a tailspin as a result of poor management, massive corruption and unfavorable global conditions -all compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent polls suggest that neither Erdogan nor his alliance with the ultranationalist National Movement party could beat the opposition in presidential and parliamentary elections that are due to be held in 2023.

US officials will continue to put the pressure on Erdogan, further sanctioning on Turkey is still possible, knowing that time runs against Erdogan and Turkey finally will prefer the butter and not the guns in its ”guns-butter dilemma”. But how Erdogan will deal with American pressure on him remains a mystery. Even if Biden succeeds in shifting relations with Turkey in another direction, it is unknown whether or not it will improve ties between Washington and Ankara. To do that, it would require some agreement on where to begin addressing issues. With a list as long as the one that has weighed down US-Turkey relations for several years, this will be no easy task for the new Biden adminstration.

Ten years ago, “The Atlantic” ran as its cover story a piece titled “The Ally From Hell”. The article followed the raid that killed al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and was focused on the relationship between the United States and Pakistan, and especially on how Washington’s key ally in the War on Terror contributed more to the problem than to the solution. In the final line of its conclusion, it read “There is no escaping this vexed relationship -and little evidence to suggest that it will soon improve.”

Such a description has in several ways grown to apply to the United States’ relationship with Turkey in the last decade. There does remain room for the Biden administration to prevent relations with Turkey from plunging to deeper lows. That said, it will mean starting small and keeping expectations in check, lest it wants to see Turkey go from a flawed partner to a second “ally from hell.”

In light of all of these developments, the S-400 issue and the U.S. renegotiation with the YPG will continue to be the defining agenda in the coming days.